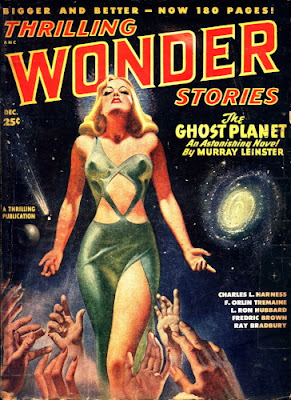

THE GHOST PLANET

a short novel

by MURRAY LEINSTER

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Thrilling Wonder Stories December 1948.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER I

Solar Newcomer

Tom Drake was the first human being who is known to have come in contact with the inhabitants of the Ghost Planet. At the time the Ghost Planet wasn't even a name. It was undreamed of.

More, Tom had to admit that he neither saw nor heard nor felt the creatures whose existence he reported. The instruments of the Weddington had recorded absolutely nothing out of the ordinary. So, on his arrival at Earth, Tom was politely fired from the staff of the Blair Memorial Expedition to Titan and found his affairs in a parlous state.

The encounter itself almost justified that action. The Weddington was the emergency craft left on Titan with the observing members of the expedition. After eleven months of routine observations temperaments clashed, crotchets developed and lunacy impended. So the Weddington was sent back to earth for mail, reading-matter and visi-records to save the situation.

Because of her size, only two men were required to man her. One was Tom Drake, who had no nerves and was the lowliest member of the expedition's staff—the other navigating member of the crew, was the most high-strung and nerve-racked of the whole force on Titan.

Four days out toward Earth he blew up with a loud report and had to take a hypnotic for twelve hours of restful slumber so he could continue to navigate the Weddington. The Weddington's course was close by Mars then and, while the navigator snored heavily in his bunk, Tom Drake took post in the control room and relaxed.

It was very lonely. The sun was a small round flame. The stars were many-colored unwinking specks of light. Tom Drake regarded the instruments which said that the little ship went on her course without incident. Mars was a dim red disk of pinhead size far off to the left.

The tiny ship went streaking through emptiness without any of the ghastly sounds her drive produced in atmosphere, leaving behind the thinnest and most tenuous of tails, which was created by the infinitesimal exhaust of ionized gases.

Later Tom was inclined to credit the whole thing to that tail. The Weddington was still accelerating and would do so for three days more, switching to deceleration well past Mars. Partial compensation for acceleration allowed of a high speed-gain rate.

Everything seemed utterly normal—depressingly so, in fact. The exploration of the other planets of the solar system had been disappointing. None would support a colony. There were observatories on Mars and Luna and Mercury, but the Weddington was alone in emptiness.

Tom thought regretfully of ancient dreams of interplanetary commerce and almost resentfully of the recent tendency not even to dream of interstellar journeyings.

And then he saw something odd.

It was a tiny speck of mistiness, perhaps half the size of the disk of Mars. It was almost in line with the red planet. And in interplanetary space there should be nothing misty save comets. Tom regarded it absently for a moment, then swung a telescope to bear.

It was a globular mass of unsubstantial reflecting stuff, like a puff of smoke in emptiness. Which, of course, was impossible. Also, this particular object was new. It hadn't been in sight in the neighborhood of Mars a little while since.

Presently it was larger and its angular distance from Mars had increased. Since it was on the side away from the sun and the Weddington sped sunward, that made him stare. He took a reading of the angle between the mist and the planet. Ten minutes later the mistiness had increased in size by several seconds of arc and the angle between it and Mars had decreased again.

The logical inference would be that it was between the space-ship and the planet, that it was moving nearer to the space-ship and that it had just changed course. But that was preposterous! The thing had no substance! In the telescope he could see fourth magnitude stars through the very center of the mist.

Half an hour after he first sighted it, it was on the sunward side of Mars and was larger still. Had it been a solid object he would have considered that it was accelerating at a terrific rate and speeding to intercept him.

But it was not solid! Not only could he see remote stars through it but, when he turned a radar-scanner on it, the instrument registered exactly nothing. There was not even a tiny meteorite in its center. There was nothing there except mistiness. But it continued to move and grow.

He went back to rouse the navigator but could get no response. Hypnogen tablets aren't habit forming, but they are powerful and the navigator was out cold. Tom returned to the control room and regarded the mistiness again.

As nearly as he could tell the mist was headed on a collision course and accelerating at four or five gravities. He cut off the Weddington's drive, so the little ship would merely drift on with her attained speed and without acceleration. That should make the misty globe pass on ahead.

But it changed course. From terrific acceleration, too, it began suddenly to decelerate. It would still meet the Weddington in space.

It was not solid. The whole business was unthinkable, but Tom sweated suddenly. He thought of all the wild imaginative tales that had been written about monsters of space. He used the gyros to swing the Weddington about. He blasted recklessly at two gravities at right angles to his former course.

The mist swerved and continued to grow in size.

An hour after his first glimpse of it the misty sphere was very near indeed—so near that there could be no possible question that it meant to close with the Weddington. Tom Drake sweated profusely. He sent the small emergency-ship in crazy gyrations at all angles and all accelerations up to four.

The unsubstantial sphere followed each change of direction with precision. It matched his speed. It reached a point no more than a hundred yards away and kept that distance for long minutes through dozens of maneuverings.

It was a diaphanous globe of utter unsubstantiality. Stars could be seen through it clearly. Yet it seemed to Tom that some distant stars were dimmed a little more than others, as if the mistiness varied in thickness with an internal structure. He had a good opportunity to make these observations. The sphere was a good thousand feet in diameter and for minutes it clung close, no more than three hundred feet away. Then, suddenly, it closed in.

And nothing happened. Absolutely nothing. The Weddington was enclosed, was engulfed in the mist. But no alarm bell rang. No instrument showed the slightest change of registration. Indeed, staring out from within the substance of the globe, it was hard to detect any difference in the look of things. But the Weddington was unquestionably in the very center of the sphere of mist.

Tom Drake had an eerie feeling that he was being watched intently by sentient beings. He knew that from a little distance his ship would appear to be the center of a sharply edged, ball-shaped nimbus like the head of a comet. He knew that something was watching him. He sweated. But no instrument needle swerved from its peg, nothing happened and nothing happened and nothing happened.

Then the globe suddenly shifted. It was off to one side. It moved swiftly away. It headed back toward Mars at an incredible acceleration.

That was all. There was no damage to the Weddington. There was no registry on any instrument tape to corroborate Tom's impressions. But the memory was very vivid. Tom had the curious, unpleasant impression that he had been examined intently by ghosts and then left behind when their curiosity was satisfied. It was not a nice feeling.

When his navigator woke he told him about the visitation. The navigator was annoyed. Tom's tale was nonsense. The Weddington, though, was off-course and that was a serious matter. He returned her to her proper line and speed and fretfully reproved Tom for his absurdity.

In time he made report to the trustees of the Blair Memorial Fund. Tom was questioned. He told his tale frankly, then indignantly, then resentfully as he was disbelieved. When he was informed that his contract with the expedition was canceled he was enraged. He was practically thrown out.

He was, in fact, not only given the heave-ho but classified as an unstable personality, which would not help in getting further employment—and that was a serious matter, those days. Times were not good on Earth.

The population of the planet had increased to the point where merely living was a problem. Tom Drake nearly starved—because he'd encountered the inhabitants of the Ghost Planet before the Ghost Planet was known to exist. His friend Lan Hardy took him in while he hunted for a job.

Then, three months later, the Ghost Planet appeared in the Solar System.

CHAPTER II

Non-Material Invasion

When the Ghost Planet appeared on the far side of Neptune, of course, nobody on Earth thought it meant anything at all. The first news releases said only that a new comet had been discovered. It was coming in at a surprisingly high velocity and it had developed a head at an extraordinary distance from the sun.

It had no tail, as yet, but one was expected to form. A comet's head and tail, of course, are simply ionized gases of almost infinite thinness, driven out and away from the sun by light pressure.

Tom's friend Lan Hardy saw the news releases, mentioned them to Tom and forgot them. He was pulling wires desperately to get some sort of Guild rating that would justify Kit McGuire in marrying him. Her father had been World President and at the moment was in disgrace because he hadn't been able to stave off an inevitable economic depression.

But Lan shared his apartment with Tom and confided all his amorous dreams to him and after Tom found a job doing electronic design for a very small manufacturer he stayed on with Lan because living quarters were hard to come by.

Tom dug doggedly into books and found nothing that would explain his experience between Mars and Earth and ultimately had to work out a theory of his own. And then, without any real hope of ever putting his ideas to use, he began to work out possible devices which would prove or disprove his notion.

Even he, though, didn't connect the Ghost Planet with what he'd seen. At first it was called simply a new comet which had developed a head unusually far from the sun and so far had no tail. Besides, there was not much time given to it on the newscasts.

Even when the astronomers mentioned that its course—they said orbit—was a mathematically straight line headed accurately for the Sun, there was too much other news on the vision-screens for anybody to pay attention.

There was a scandal involving a prominent vision-screen actor. Two of the biggest Guilds had locked horns and conflict between their respective members was in prospect. A new fashion swept the earth and every woman had to get an entirely new wardrobe.

Work rationing appeared likely in North America and a new orgiastic religion turned up in Africa and spread like wildfire with a twenty percent drop in industrial production as a consequence. Nobody paid any attention to the Ghost Planet except the astronomers at the government-supported observatories on Earth, Luna, Mars and Mercury.

Then Lan Hardy—trying to play politics for advancement—got into trouble with a Guildmaster and was suspended from all connection with Guild conducted industry. It became Tom's turn to provide the cash on which both of them lived for a while.

Then the astronomers reported that the Ghost Planet—which they still called a comet—had no detectable mass and was completely unaffected by the mass of Neptune, which should have changed its line.

They added that their spectroscopes showed no sign of ionization of the gaseous mass they then considered the Ghost Planet to be and they expressed amazement at its almost perfectly globular shape. And then they observed that it had a regular diurnal rotation, proved by the Doppler-effect difference between the light of opposite limbs.

Still there was no public interest. A mutation in soil bacteria in Western Europe threatened the fertility of ten percent of the world's tillable soil. Chicago won the World's Pennant. The world government administration which had taken over from Ex-President McGuire raised taxes all around and blamed his regime for the necessity.

The Seda Mountain ore deposit was officially declared exhausted. A new vision-screen comedian shot up to the top of the popularity polls. The value of the prizes for naming "Mr. Sh-h-h-h" on a quiz program mounted to $120,000.

And Lan Hardy was told that since he was suspended from his Guild—which was worse than expulsion, because he couldn't even try to join another—his quarters in a Guild-owned building had to be vacated. So he and Tom had nowhere to live.

Their personal dilemma bothered nobody but themselves. Even their friends joined the rest of the world in absorbed attention to the prospects and games of the Interhemisphere Polo Games, with the usual rumors of fixing, bribery and deliberate injury of players.

In the week before Lan and Tom were to be evicted, while they sought vainly for other lodging, Australia came from far behind and classified for the finals against the Hungarian five. Ex-President McGuire forwarded to Earth Government a heavily worded statement which those then in office unanimously ignored.

An atomic-energy plant in Patagonia flared blue and was automatically dumped into the pool of cadmium its flaring had melted. There was a prison break in Montreal. There was an airways accident on the Honolulu run.

Nobody thought about the Ghost Planet, now a flaring globe of unsubstantiality some thirty-two thousand miles in diameter, heading in past Mars.

Then there came the night of the final Interhemisphere polo game. Tom and Lan saw it on the vision-screen from the lodging they were so soon to vacate. They were watching keenly with the feeling of absolute presence. They saw the multiple-balconied stands about the field, the black and cloudy sky overhead and the playing field itself in its glare of invisible, non-glaring lights.

And in the second chukker, as there was a tumultuous rush of men and horses after a racing ball, something thin and pallidly glowing and a thousand feet through seemed to settle down above the lighted field. It was barely visible on the vision-screen until the roaring of the crowd changed to panicky shrillness.

Then the sports announcer said crisply, "Something queer in the air. It's barely visible. I'm changing the contrast."

The seeming soft lighting became harsh and hard and the vision-camera swung upward and the photographic quality of the lens grew hard indeed. Grainings appeared even in the night clouds overhead. Then the vision grew clearer.

It was a round globe of mist, almost motionless in midair over the polo field. It was not substantial. When a search beam struck it the light went right through but, in puncturing, it seemed to disclose structure inside.

And the internal details, misty as they were, were not the random swirling patterns of mist but very specific lines and masses and angles which were convincingly artificial. It looked very familiar to Tom.

A rocket soared upward from the stands. It had been placed to announce the victors of the polo game. It spurted through the wraithlike phenomenon unhindered and burst through in a spray of blue lights above it. Those lights drifted down through the wraith and reiterated the look of artificiality about its inner changes of thickness. They went out.

The globe did not stir, though search-beams showed the smoke trail of the rocket blowing sidewise through it. Had it been solid or real it might have looked like an alien space-ship, a spectral space-ship, curiously watching the polo game below. But it was not real. A private plane, joy-riding overhead, made an hilarious lunatic dive at the apparition, flew through it, flew through it again and nothing happened.

Presently, in its own good time, exactly as if it had lingered until its curiosity was satisfied, the misty globe rose and vanished in the darkness overhead. It acted exactly as if living beings in it had become bored or annoyed and had gone away. It was remarkably like the way that other misty thing had acted about the Weddington three months before.

"Now, what on earth was that?" demanded Lan, blankly.

Tom Drake smoked furiously and said nothing. Within minutes, the muted beep-beeping call of a special news bulletin broke into the restored but disorganized viewcast of the polo game. Jan Hardy switched to the newscast channel.

"A special broadcast of comments on the apparition at the Interhemispheric polo game ten minutes ago," snapped an announcer's voice crisply.

The face of a famous scientist peered out of the screen.

"I was watching the game," he observed. "Until the recorded telecast can be examined in detail, I can say only that it appears to be a very curious meteorological phenomenon. Akin, perhaps, to radar-ghosts, which are well-known and still not fully explained."

His face vanished. An eminent physicist took over.

"Very quaint, I would suggest a projected image of some sort, thrown into emptiness by practical jokers, except that it reflected light thrown upon it. That suggests that it was material. On the other hand no material substance known can be penetrated by other material substances without some disturbance of the penetrated substance."

His face disappeared. The world's best-publicized vision comedian appeared.

"My head felt that big this morning," said the comedian and hiccoughed in his inimitable fashion. Undoubtedly, it evoked gales of laughter from his faithful fans. "I wondered what happened to my hangover. It went to the polo game!"

He leered in his equally famous manner, and his face faded.

Other faces and other voices. The special-events vision department dragged in all the big names that could be reached within the spot news time limit. Some hedged. Some tried feebly to wise crack. Some uttered profound nothings. It was the standard sopping-up process designed to get the maximum out of any news event that went on the air-waves. Lan Hardy scowled.

"But what was it?" he demanded again. "This is just junk we're getting!"

The screen flickered again and there was ex-World-President McGuire looking heavy-lidded out of the screen. He spoke with deliberate energy.

"I happen to know what the apparition was. I have had private reports. Similar phenomena have been reported on Mars, Luna and Mercury. Moreover, the survey-ship Arcturis passed close to the reported new comet on its way back from Jupiter. Copies of photographs taken of the appearance were sent me by personal friends.

"The appearance over the polo field was similar in kind to the new comet. It came from the new comet. Two photographs of the comet show such globes as we have just seen, arriving at and departing from the so-called comet.

"I have informed the World Government of those facts. The Government will doubtless issue a communication on the nature of the so-called comet and such globular artifacts as the vision-screen just showed us."

His voice ceased. The screen went blank. A smooth anonymous voice said, "This concludes the special-events broadcast about the appearance at the Interhemispheric polo match. Further details will be included in special feature broadcasts at the regular hours."

Tom Drake said slowly, "Globular artifacts."

"Crazy, eh?" said Lan brightly. "He's a fairly decent sort when you know him though. Kit likes him, even though he's her father. Fairly decent to me, too."

"I wonder what he heard from his private reports," said Tom. "I'd like to talk to him. I'd like to see those reports. I wonder if we could query it?"

Lan shrugged. Tom punched the dials on the vision-screen and a newsfile clerk looked impersonally out of the screen.

"What's the data on this new comet?" asked Tom, frowning. "The one McGuire just mentioned?"

"I do not recognize the reference," said the newsfile clerk detachedly, "but the new comet file will be projected for you."

There was a click and the typed record of newscasts appeared on the screen. Tom read absorbedly. Orbit ... mass zero ... diurnal rotation ... un-ionized gases.... As he read the pulsing blue glow of a personal communication call appeared on the screen under the file image. He threw the switch to take the call. The newsfile faded. Kit McGuire looked appealingly out of the screen.

"Oh, Tom! How-do! Do you know how I can locate Lan? My father wants him to come out here—"

"He's right in this room," said Tom.

"Thanks. Lan—can you come out to the Coast at once? Father wants some specialists. It's that new comet business. I told him you'd come and might find another good man or two for him."

"I'll take the next plane," said Lan, beaming. "I'm being evicted anyhow. But about someone to bring along—"

"Me," said Tom briefly from the background, "if I'll do."

"Sure!" said Lan. "I'll bring Tom. We're practically on the way!"

Kit smiled at Lan. Fondly, almost tenderly. But her forehead was creased a little with worry.

Tom said, "What's up?"

"Father," said Kit, "made the mistake of calling the Government's attention to the new comet. So they're ignoring it just because he mentioned it. And—it's stopped."

Lan feasted his eyes upon her.

Tom said sharply, "What's that?"

"It's stopped," Kit repeated. "It was headed straight in for the sun. And it's stopped. It's standing still out in space between Earth's orbit and Mars."

"Oh, it couldn't do that!" protested Lan. "It simply couldn't! Heavenly bodies can't stand still!"

"This one does," insisted Kit.

"Then what's up?" asked Lan. "Are we to get it started again?"

He grinned and Kit smiled in return. But she looked directly out of the screen at Tom Drake.

"Father says it isn't a comet," she told Tom. "He says it's a planet. A ghost planet. And somebody has to find out what it wants."

Tom jumped. The term "ghost planet" was something to make him sit up. It suggested—many things. Tom didn't happen to agree with Kit's father politically, but he did respect the older man's brains. And this meant something! His own brain went into high gear.

While Lan filled out the call from Kit with zestful, romantic conversation, Tom Drake put together the things he knew and some things he wouldn't have guessed without that "ghost planet" phrase. They added up to a brand-new concept which was upsetting.

He was packing his own possessions for travel when the call ended and Lan came in, smiling sentimentally.

"Funny, eh?" said Lan comfortably. "Kit's actually worried!"

"So am I," said Tom. "It didn't occur to me before but now I begin to see things. I saw one of those globes three months and more ago, out by Mars. I couldn't make myself believe what it pointed to. It was a scout. You see?

"Looking over our solar system for whatever it wants. And it must've gotten an idea that what it wants is here and—well—the planet followed it. It was a ghost space-ship from a ghost planet and it didn't come here for fun. What would ghosts living on a ghost planet and running ghost space-ships be wanting of Earth, Lan? Whatever it is I'd hate to have them find it!"

CHAPTER III

Go West, Young Men

They left New York on the midnight plane and four hours later they stepped off at the landing field at Pasadena. Ten minutes of shuttling and they came above-ground at the very edge of the solidly built city. Kit waved to them from her father's groundcar. It was still midnight by clock time.

The groundcar drew up beside them on its two wheels. They entered and it went hissing softly out to the openness beyond the city's limits. One had to be rich to live outside a city these days.

The Guilds had taken over the functions of insurance organizations, lodges and unions all in one, and building was now so costly that only a rich man could own an individual dwelling on an individual plot of ground. The Guilds themselves owned a good half of all the dwelling units in America. So people looked envious as the groundcar sped out on an arrow-straight road toward darkness.

It was almost the only private car in view. There was traffic but it was gigantic ten and twelve and twenty-wheel trucks and trailers. The groundcar dodged among them with needed agility and Kit spoke briefly as she drove. She was accustomed to this sort of traffic. The pressure of existence on an overcrowded world had made private vehicles almost as rare as private houses.

"Quite a lot has happened since I called you," she said curtly. "Father spoke over the visioncast about the thing that appeared over the polo field tonight."

"We saw it," said Lan. He shifted his position to be closer to her on the upholstered seat.

"An hour later the Administration told the newscasters that Father's report had been received. Their only comment was that he seemed to be very ill! They were hinting that he was crazy!" She laughed angrily.

Lan Hardy said softly, "Was that why you wanted me to come, Kit?"

"I want you to help prove he isn't crazy!" snapped Kit. "Just because he's unpopular because he tried to be a good President, they're trying to get more popular by ridiculing him!"

Tom said meditatively, "Some people think he was not only honest but intelligent and that he had the right ideas as President. Naturally the politicians who replaced him don't like that!"

Kit turned to him eagerly. "You're for him, then? You think he was a good President?"

"I disagreed with him practically all the time," admitted Tom, "but I did think he had brains—just not the kind for that job. I'm much more interested in—"

"I'm not interested in your interests then," said Kit icily. She turned warmly to Lan. "Lan, the problem for you to work on is a way to prove that the Ghost Planet and those globes are what my father says and that they're dangerous and something has to be done about them!"

Lan put his arm along the back of the seat behind her. He talked soothingly in her ears. Tom sat in silence as the groundcar tore through the night. Presently he looked thoughtfully up at the stars. He watched them, continuing to piece things together.

Suddenly he said sharply, "Pull over to the side and stop the car, Kit!"

"Eh?" asked Lan, startled. "What's the matter?"'

"Pull over and stop!" snapped Tom. "It's important!"

In silence, Kit swerved the vehicle and went onto the shoulder of the highway. She stopped. Tom spoke in a voice which sounded a little odd even to himself.

"Turn off the lights. I mean it!"

Almost instinctively Kit obeyed. There was a temporary blackness all about. There was, right here, no other vehicle to pierce the darkness with its headlights or the silence with the sound of its motor. They saw only the stars and heard only the shrill stridulation of insects and the croaking of frogs in a nearby marsh. Then Tom pointed.

"Look there! Quick!"

Against the sky a gossamer, circular mistiness moved swiftly. It was lighted by the stars which shone through it. It was moving. It was perfectly round. Perhaps—perhaps—it glowed slightly. It rose in utter silence and moved swiftly against the wind. It dwindled in size and vanished.

"That one over the polo field on the other side of the world wasn't the only one on Earth tonight," said Tom grimly. "Did you see that, Lan?"

Lan said easily, "It was the tip of a searchbeam lighting the clouds, wasn't it, Tom? What of it?"

"That was a ghost-globe," said Tom shortly. "Like the one that chased the Weddington and caught it. It's from the new comet. From the ghost planet. It's a ghost space-ship. There may be hundreds of them searching for something here on Earth."

"Come now, Tom," said Lan kindly. "A plane dived right through the thing over the polo field. It wasn't real. It couldn't be!"

"I didn't say it was real," said Tom briefly, "but it's actual. McGuire is right. I wonder what they're after?"

Kit started the groundcar again. It went on through the night. After half an hour she turned in a private driveway and drove on a mile or more to her father's house. She parked the car by a side entrance and led the way within.

Her father was in his study. It was an engineer's study, with a great commercial fine-grain vision-screen at one end. McGuire himself, heavyset and prosaic as in the newscast, sat regarding an image on the screen, shown with even greater perfection of detail than the news screens would portray.

It was undoubtedly an image sent from some technical service on a commercial wave band. The image was that of a field of stars, in the center of which a sphere of pale mistiness hung stationary. Stars shown behind it. Stars shone through it. The magnification was so great that the slight oblateness of the wraithlike globe was visible. The image was almost a yard across.

He swung in his chair as they entered, nodded to Lan, acknowledged the introduction to Tom and waved his hand at the screen.

"It's stopped dead," he said heavily. "This image is from the Yerkes telescope. Six hours ago it began to decelerate at a rate of close to four gravities. It was going nearly two hundred miles a second—faster than any interplanetary space-ship we've ever made has built up to. In two hours it was down to a dead stop. And it's stayed stopped."

Lan said brightly, "Very interesting, sir."

"Smaller globes, like the one over the polo field, have been seen going to it and coming from it," McGuire added heavily, "but I can't seem to get any—"

"We saw another, sir," said Tom, "on the way here from town. And I saw one nearly three months ago, out near Mars."

McGuire swung in his chair. "Yes?"

Tom told the story of the Weddington and the ghost-ship. "When I was in the middle of it," he finished, "I had the feeling that I was being watched. But my report got me fired from the Titan Expedition as a lunatic."

McGuire asked crisp questions. Mostly they were technical ones, about acceleration of the ghost-ship and the like. McGuire had been an engineer, not a politician, before his election to the World Presidency and he was not thinking like a politician now. He was absorbed in a problem in whose importance he believed.

But Lan interrupted the questioning to say respectfully, "You can count on us to do any work you need done, Mr. McGuire. Have you anything in mind for us to do right away?"

McGuire looked at his daughter's fiancé detachedly. "I'm waiting for reports," he observed. "It was Kit's idea that you might be useful. Any suggestions?"

"No, sir," said Lan cheerfully. "Only that we get our luggage in from the car. I'll do that, sir."

He made a graceful exit, followed by Kit. Tom stayed uncomfortably where he stood. "I've got a rather crazy idea, sir," he said awkwardly. "It comes from a theory—"

A speaker unit spoke with startling clarity from the wall. "A number of mist-globes are leaving the sunward side of the large sphere. They appear to be arranging themselves in a geometric pattern."

McGuire pressed a button and the image on the screen changed to an even more enlarged view of the ghost planet. Only a part of its edge was in view, now. And there was a distinct formation of tiny, almost transparent objects moving away from it.

There were dozens of them. They spread out in an expanding V and moved steadily across the star-speckled background. They looked like bits of thistledown in space. Stars shone right through them.

The speaker unit said crisply, "They are accelerating at four point two gravities. Their course appears to be toward Earth."

McGuire watched. Tom drew in his breath sharply. He reached forward and touched the screen.

"Look!" he said sharply. "If this Ghost Planet were solid—see? There'd be mountains here!"

There were small but distinct serrations at the edge of the almost transparent disk. The loudspeaker spoke again.

"This is the third such formation that has moved toward Earth in the past four hours."

"And the Administration says I'm crazy," said McGuire wrily. "Strictly speaking, it's none of my business. It should be left to official departments. But I was head of the government for awhile. I know better than to think the only duty of a private citizen is obedience!"

Then he reverted to Tom's comment. "Of course they're mountains. But they're mist. They're impalpable. They're imponderable. They're unreal! But if they were real—if a planet thirty-odd thousand miles in diameter moved into our solar system and its space-ships began to explore Earth in squadrons—then I think the Government wouldn't call me crazy!"

Tom said carefully, "There is—er—substance of this sort known?"

There was another booming voice from another room beyond McGuire's study.

"News bulletin! News bulletin! Two misty objects or apparitions like that seen over the interhemispheric polo match some hours ago have appeared over Honolulu! They are hovering over the city now!"

Kit appeared in the doorway, her hair a little disheveled. "Father! Did you hear that?"

McGuire got up and walked heavily out into the next room, where a standard broadcast vision receiver had interrupted a period of romantic music to bellow out the news. The technical screen in the study would remain on the observatory beam McGuire had arranged for. This was a news broadcast all the world would see. Lan Hardy got up hastily from a sofa. Tom observed that he looked annoyed.

The three men—McGuire, Tom and Lan—watched the news broadcast in silence while Kit looked from one to another of their faces. This vision cast was not as clear as that from the polo field. The misty globes were higher and not as well lighted, even though search-beams sought them out and followed them.

The two globes drifted over the city, stopped together, moved onward together, made systematic circlings as if inspecting everything below them with great care—and went off into the darkness.

"Well?" said McGuire when it was over. He spoke to Tom. It apparently did not occur to him to question Lan.

Tom hesitated. Then he said, "Look here, sir. We say things are real or unreal as we say they are red or green. But there isn't any absolute redness or greenness. Things are just more or less red or green.

"We recognize that redness and greenness are abstractions only. Maybe reality and unreality are more or less abstract ideas too. Maybe nothing is wholly real and nothing is absolutely unreal."

McGuire stared at Tom. Thoughtfully. "Mmmmm. Go on."

"Maybe there's no absolute reality," said Tom. "Just as there's no absolute red. And maybe there's no absolute unreality. There are some suns in the star catalogs that are known to have densities as low as the vacua in X-ray tubes.

"That's not matter in the ordinary sense of the word. Those suns glow, and they exist, but they're on the border of unreality. If this ghost planet and these globes are like that—"

McGuire looked at him in a curious mixture of approval and doubt.

"If they are—"

"If there's a type of matter on the borderline of reality, it might be matter on the borderline between our cosmos and another. Matter not wholly real in our universe, but not wholly unreal either. Possibly—well—latent matter. Like latent energy. Like—say—trigger-energy or atomic energy.

"It would be real enough in its own universe. It would even have an infinitesimal, perhaps immeasurable mass in this. The point is that if this were a planet from a ghost sun, searching for something here—it wouldn't be here for the trip.

"And it would have some way either of turning into matter which was real here or of making our matter into its own kind. Its space-ships are spying on us. It must have a purpose. It could be—"

Tom hesitated. "Apparently its space-ships have been making public appearances to see if we have any weapon we can use against them. When they find we haven't—when they're sure—they'll probably begin to seize on whatever it is they want of us."

McGuire said practically, "And what would you guess that to be?"

Tom shrugged. "They could get any possible mineral matter from Mercury, and most organic materials from Venus. But there's no intelligent life except on Earth. Would they want intelligent creatures—in short, men? I don't know."

But as it happened Tom made that guess just eight hours before the first human being, in Cleveland, Ohio, was engulfed in a misty globe which came down from the sky and enclosed him—and then, before the eyes of his goggling fellow-humans, turned him into mist like the thing which had captured him.

CHAPTER IV

Political Implications

It is always dawn somewhere on Earth. Tom Drake saw the sun rise where he worked feverishly in the private laboratory attached to McGuire's house. McGuire had been an eminent engineer before he became the most unpopular president the World Government ever had.

He was a sound thinker even after he was retired to private life and became the Earth's most scorned private citizen. He was equipped to verify, with his own apparatus, any material and any calculation used in any type of engineering design he was likely to be concerned with.

Tom worked all night long till sunrise, putting together an unlikely small contrivance which—if it worked—would tell something about what the ghost-globes were made of. If one could be contacted.

Meanwhile there was panic in Calcutta where a religious festival procession turned into stark terror-stricken flight when a ghost-globe settled down in the middle of it. But the ghost-globes were merely facts.

They rated with flying disks and other phenomena which at various times had been credibly reported by large numbers of people and then had ceased to be reported and been dropped into the limbo of forgotten things. The globes had been broadcast, to be sure, but nobody—except ex-President McGuire—had an explanation for them and nobody was willing to take his word for anything.

He'd become World President because the public was tired of professional politicians which were nothing else. He'd suffered the fate of all men less thick skinned than professional politicians. When, returned to private life, he tried to do a public service he was ignored.

Part of that ignoring took the form of playing up all other news items than the ghost-globes and the ghost planet. A woman in Cairo had quintuplets. A London-Ottawa plane crashed on landing and a hundred and twenty persons were killed.

There was a school fire in Johannesburg, an unusually gory murder in Stockholm, a quaint "royal" wedding between members of formerly royal families in Central Europe, with ancient pomp and ceremony. There was a jurisdictional dispute between two Guilds which was threatening to throw two hundred thousand men out of work because of the question of the classification of four jobs in an atomic-power plant in Siberia and the regular run of sensational and merely idiotic news.

But one item made the morning newscasts about the globes. One of them settled upon the Smithsonian Museum main building in Washington. When the sun rose in the Eastern time-zone the globe enclosed two-thirds of an antique building dating from the early twentieth century.

It was pale and thin and wraithlike but the morning sunlight showed it clearly. It looked rather like a balloon of sheerest gossamer except for those disturbing hints of internal structure.

For some reason unknown fire engines were called out. They poured huge streams of water upon and into the wraith. The streams went right through the uncanny sphere. The buildings of the Smithsonian—not only the one englobed, but others nearby—got very, very wet. There was no other result that could be detected. When the globe got ready, in its own good time, it lifted from the drenched structure and vanished in the sky. That was all.

But that was at dawn on the Eastern coast. At that time Tom Drake worked obliviously in McGuire's laboratory. He did not even hear the spot news announcement. The dawn traveled westward and the cities woke in their turn. Buffalo woke, and Cleveland, and Detroit and Chicago.

The dawn went on toward the Rockies. It crossed them. And Tom, in Pasadena, blinked wearily at the new-risen sun in the Pacific time-zone when the globes took their first specific overt action against a human being.

It was in Cleveland at a quarter to nine, local time. The morning rush to work was in full swing. Away downtown, where Euclid Avenue runs into Lincoln Square, the sidewalks were crammed with workbound pedestrians. It was an extraordinarily bright and sunshiny morning for the city of Cleveland.

The air was utterly clear and the look of things was normal in every possible way. Hurrying, crowding people—stenographers, bookkeepers, minor executives—salesgirls, porters, typists, clerks. The sidewalks were crowded and the pavements between were jammed with traffic.

Even the walkways around the very ugly Lincoln Monument were filled with people using them as short cuts across the square. Everything was exactly as it had been ten thousand mornings before and could reasonably be expected to be for ten thousand mornings after.

But suddenly, above the noise of feet on concrete walks and the sounds of traffic in the streets, there came a high shrill scream.

It was not a scream of pain but of terror. A man stood stock-still and shrieked. He was an absurd, pudgy, bespectacled man with a ridiculous mustache. He was later learned to be a certain Arthur V. Handmetter, a foreman in a factory making artificial flowers. He stood as if frozen on the sidewalk with his eyes wide and staring. He screamed and screamed and screamed.

Other figures shrank away from him, clearing a space and staring at him. There was absolutely nothing that they could see at first to account for the pudgy man's panic. He screamed again and again and a policeman shouldered through the crowd toward him.

Then the crowd noticed that his screams grew thinner. Standing there before them in a ten-foot cleared space, the little man's shrieking grew muted as if far away. His mouth was open and his body was rigid in a paralyzed horror. But his voice grew thinner.

Perhaps, at this time, some of those about him began to notice that the clarity of the morning air had faded a little. The sky was not quite so blue and the sunlight was dimmer. But they noticed first that his body began to grow translucent. His screams had only the volume of whispers then, but they were high pitched and penetrating.

The policemen tried to seize him. Then there was panic unutterable. The policeman's hand went through the arm of Mr. Arthur V. Handmetter as if it were smoke. The people about him fled in stark unreasoning terror, turning wide and horrified eyes behind them as they fled.

They saw Mr. Handmetter become more and more translucent and then become transparent—still making the faintest of shrill screams—and finally he faded into nothingness in the deep shadow which had fallen imperceptibly upon the square as he vanished.

When he had gone—then quite all of the square and blocks of Euclid Avenue itself and other blocks of other streets opening into the square became like madhouses. Those who had known only of something strange occurring in the square and had been craning their necks saw more than they had bargained for.

They saw a great, thousand-foot globe acquire the seeming of substance, bit by bit. At the beginning it was so thin and so tenuous that none really saw it. But as the substance of Mr. Handmetter diminished the substance of the wraith increased.

It became misty even in the sunlight. It grew smoky. Partitions and floors appeared within it. Shapes moved, dimly seen through its spherical walls. It grew more and more opaque—and it was an alien Thing, not wholly real but certainly not imagined.

Then the wave of panic broke in the Square. Men fled from the shadow of the thing of smoke. And, like a flood of pure terror, others turned and fled until all downtown Cleveland became a bedlam of screaming, fleeing humanity.

It was a catastrophe of major proportions in dead and injured in the crush. But actually, nothing whatever had happened save that a mist-globe had settled down in Lincoln Square, and one single human being—Mr. Handmetter—had turned slowly to mist as he screamed his horror and the mist-globe increased in thickness as he vanished.

It was a thousand feet in diameter and it had, at the end, just as much of substantiality as a globe of smoke containing a hundred and fifty pounds of substance might have had.

But then it rose sedately from the square—the ugly Lincoln Monument withdrawing from its substance as the globe arose—and ascended swiftly and diminished to the size of a tennis ball, then to the size of a marble, then to a spot and a speck and a mote—and then vanished utterly.

Mr. Handmetter, of course, vanished with it.

Out near Pasadena Lan Hardy smiled brightly at Kit across the breakfast table. It was one hour later by actual time, and one hour earlier by local clocks. Tom came in from the lab, McGuire following him. They sat down at the table. Tom looked discouraged. McGuire drank his coffee without a word.

"Father," said Kit. "What do you think of that Cleveland affair?"

McGuire nodded at Tom.

"It knocked my ideas all out," said Tom. "I should've known it in advance, though. But now I know that what I was trying to make wouldn't work even in theory."

Lan said cheerily, "Why didn't you ask me to help, Tom?"

"I was doing it by ear," said Tom morosely. "Trying to work out a theory that would work by finding out what didn't."

McGuire said abruptly, "You had some good ideas, though."

"What were you trying to do?" asked Kit.

"Trying to make a ghost," said Tom, sourly. "That Cleveland business shows it can't be done without ghost material to swap. But it's perfectly obvious once you see it! I made a fool of myself!"

Lan Hardy attacked his breakfast with a hearty appetite. He smiled sentimentally at Kit from time to time.

"This young man," said McGuire, almost grimly, "has an idea that fits the pieces together better than anything else that's been suggested to my knowledge. There are stars which shine and are quite actual but with no greater densities than the vacuums in vision-screen tubes.

"They are matter as compared to the emptiness of interstellar space, but a star shouldn't exist with no greater density than that. There've always been mathematical difficulties in computing their constants. So Tom suggests that they're actually ghost stars—stars of which the planets will be ghosts like the one between Earth and Mars."

"That's the idea you sprang last night," said Lan, smiling. "A beautiful way to dodge a lot of problems."

McGuire looked detachedly at Lan. He said, "His suggestion is that there may be two parallel universes with one or more dimensions in common. It's been postulated before. Some oddities in electronic behavior call for more than three dimensions in the greater cosmos of which our cosmos is a part.

"Tom suggests that a sun in that other cosmos may, because of the dimensions common to both, be on the borderline of existence in this. Conversely, a solid sun in this universe may be a ghostly apparition in that.

"Like a cork floating on water. To a fish it is perceptible but hardly significant because it only touches the water and is not in it. The ghost planet and the ghost-globes are detectable in this cosmos, because they touch it. They aren't real in it because they aren't in it. They're ghosts to us. And"—McGuire said abruptly—"that would mean that we are ghosts to them."

Lan said, "Boo!" laughing. He looked at Kit for admiration. She said impatiently, "But if they aren't real—that man in Cleveland—"

"The cork," said Tom, tiredly, "could become real to a fish if it tried to pull something out of the water. As it pulled something into the air some of it would be pulled into the water. They pulled a man into their cosmos. So some of their globe was pulled into ours."

"But—but—" Kit said uneasily. "Why'd they do it?"

"Tom's idea, and mine," said McGuire, "is to ask them, since the Government says I'm crazy. Tom encountered one of their globes three months ago near Mars. Maybe the ghost planet was on the way and that was an advance scout.

"Or maybe it was an exploring vessel and the ghost planet came when it reported a civilization here. Maybe it came to be a base for a really thorough examination of our solar system and our civilization for whatever it is that they want."

"But what is it?" demanded Kit.

Her father shrugged. "They haven't found it, certainly. Today they took that poor devil from Cleveland. Maybe they mean to ask him where it is."

"Took him—"

"Tom spent all night," said McGuire, "trying to work out a gadget to put some matter from this cosmos into that or into the borderline state at any rate. If we could do that we could communicate with them or, if necessary, even fight them."

Tom said gloomily, "But it can't be done—obviously. I see now. The amount of energy and matter in any cosmos is fixed by definition. It can't be varied. So to put something from this cosmos into another, whether it's energy or matter, an exactly equivalent amount of matter must pass from that cosmos into this. It has to be—"

He stopped short, his mouth open as if in amazement.

"That's it!" He swung to McGuire. "Of course! Can you get hold of a space-ship? Any size! Anything! We can do it."

But Lan leaned forward gracefully. "Look, Tom. You're suggesting that by pulling a part of another cosmos into this, you can pull a part of this cosmos into that. You spoke of an analogy to pulling a cork down into water by making it pull a fish out of water. But don't you see that on an atomic or molecular scale such an arrangement would be unstable? They'd tend to pop back into their own space."

Tom shrugged. He was about to say that the ghost-ship had managed it in Cleveland.

But Lan went on gently, "Really, Tom, before you demand that Mr. McGuire get hold of space-ships and such things—don't you think you should—well—consider the facts? After all, Mr. McGuire has so much more experience than you have and is so much better qualified in every way, that—well—your theories are interesting enough—"

McGuire said sharply, "Your friend has some theories, at any rate. Have you any to offer?"

"Kit asked me to come here, sir," said Lan brightly, "to do technical work. Lab work. I've been ready to get to work at any instant, sir. But I wouldn't presume to make suggestions."

McGuire stared at him. Then he said shortly, "Let Kit brief you, then, and see if you can come up with some contributions to equal your friend's. This isn't a ceremony. It's an emergency, with a pack of politicians too busy thinking of politics to see what they're up against!"

Kit said eagerly, "You see, Lan, Father feels—"

"I know how I feel!" said McGuire angrily. "You're loyal, Kit, but I'm not thinking of the Ghost Planet as a matter with political implications! When there were different nations on earth there was a loyalty called patriotism. Now that there's a world government, there's still room for a similar feeling!

"I think the Ghost Planet represents a possible danger. What happened in Cleveland just now is evidence for that view. But I'm sure that the Ghost Planet has the secret of the answer to the most desperate need of humanity.

"So as a private citizen I think it's up to me to try to find that out! I think it's up to Lan and Tom and everybody else! And if Lan will pay less attention to the possibilities of being flatteringly respectful to me and try to suggest something useful I'll like it better!"

He strode angrily from the room. Lan flushed hotly and looked at Kit. "I'm not very popular with your father," he said resentfully.

"Don't be silly!" said Kit. "Because you're engaged to me you feel awkward with him. He won't bite you, Lan! Talk things over with Tom and work out something! That'll please him!"

"But it's ridiculous!" protested Lan. "There's bound to be organized research done! What can one or two or three people, working alone, do with problems that call for full scale planned investigation?"

Tom said nothing. He was at once very weary and very much absorbed in the new idea that had occurred to him.

"And he talks in riddles!" said Lan indignantly. "If it's a ghost planet with ghost space-ships why—he seems to agree with Tom that they can't do anything! And as for having a secret solving the most desperate need of humanity—"

Tom said abstractedly, "Interstellar travel, Lan. We've been to all our own planets and not one will support a colony. Earth's getting overcrowded. And our interplanetary drive wouldn't begin to reach even Proxima Centauri, even if we could live long enough to get there.

"The Ghost Planet came from beyond our system. They've a drive that will take a planet from one star to another. If we had it we could hunt out planets to colonize. There are plenty if we could reach them. And Earth would be a better place."

Kit said urgently, "There! That's it, Lan! Work out a drive that would serve for interstellar travel—after this affair is done with!"

Tom got up. "I've got to get back to work on a new angle. With a space-ship, even a little one, I think we could handle things."

The vision receiver was barking a news announcement as he left the room. The announcement was that a sphere was headed back toward the shimmering Ghost Planet—but "comet" was the word still used—and that it was much denser than any other that had been observed.

It was assumed to be the globe which had snatched a citizen from Lincoln Square in Cleveland and increased markedly in density while doing so. Moreover, several other extra-dense globes had risen from earth and were assumed to be heading back in the same direction.

At the very end of the news broadcast, an official announcement from the government public information service was read. It stated that Government scientists were actively investigating the comet and that the public should not be alarmed. There was absolutely no evidence—said the release—to support any idea that either the comet or the mist-globes were hitherto unknown forms of life or that the globes were likely to prey on humanity.

The release was very comfortingly phrased, but it was a mistake. Few people, if any, had heard any rumor suggesting that the ghost-globes were creatures which might eat men. The information release spread the suggestion on world-wide newscasts. It sent a wave of hysteria around an overcrowded, overemotional earth.

CHAPTER V

Uproar

A hundred years of peace and preventive medicine had sent Earth's population soaring. From two billion people in the early twentieth century it was now eight and a quarter billion. In a world-wide culture of high development there could be neither plagues nor wars to ease the pressure. But the pressure was enormous.

The Guilds arose to meet it—grim associations of individuals, at once unions and fraternal organizations, which watched jealously over the rights of their members and helped them by cooperative housing and merchandising activities to meet the increasingly desperate pressure of overcrowding.

But no organization could meet the actual situation, which was that of ancient China, static for two thousand years from the same insensate pressure of population. All Earth faced the prospect of a frantically struggling stasis with no hope because there could be no escape.

Men like McGuire saw the situation as desperate, and were howled down because they wanted to throw all the resources of the world behind an all-out attack on the means of emigration to the stars. It would be infinitely costly and taxes were already too high—demands for ever-greater government services were unending.

Even now the government regulated details of life that before had been strictly personal decisions. A vast straining electorate demanded the impossible and denied the only means for ultimate relief because they required immediate sacrifices.

An enormous emotionalism had developed, which was channeled by skilful political propaganda. But the tensions of merely securing a livelihood made Earth a place in which almost anything in the way of mass hysteria could happen at almost any instant, simply because ninety-nine percent of all human beings had been forced not to think beyond the stress of today and now.

So Tom Drake went back into McGuire's laboratory and worked and worked and worked. He had begun to think about the ghost spheres because he'd encountered one and it had caused him personal disaster.

When the Ghost Planet appeared, and Kit had called for the two of them—Lan and himself—to come out to the Coast for work on the problem it presented, he'd first thought of it as a matter of scientific interest.

But now that Lan's peevish indignation had made him realize what McGuire saw in the coming of the Ghost Planet, he worked with an enthusiasm which ignored the possibility of fatigue.

If the Ghost Planet had the secret of interstellar travel—and it must—then the problem was not that of meeting a danger, but of the whole future of humanity. As such, it was worth much more than all he could do. It was worth all that everybody in the world could do.

McGuire listened to his new plans. He nodded and vanished from the house. Tom racked his brains for remembered data and dug into McGuire's technical library for further information and then sweated over the construction of a pilot model of a small device. He could go no further until McGuire turned up with something for which a larger device could be designed.

It was dusk and he was numb with mental and physical fatigue when the air throbbed heavily about the building. Then there was a deep moaning noise and the ground trembled—and then the whole disturbance stopped with a startling suddenness.

McGuire came into the laboratory. "I got—of all things—the Weddington," he reported. "The Titan Expedition sent it back again and asked to be relieved. They were seeing ghosts and the whole outfit solemnly decided it needed psychiatric treatment."

He grinned ironically. "They've sent off relief ships, which will not investigate the Ghost Planet, to bring back the whole crowd. And they started to liquidate the equipment. I got the Weddington."

"The ghosts were thousand-foot spheres?" asked Tom, tiredly.

McGuire nodded.

"I can handle it in a pinch," Tom told him. "The Weddington, that is. Take a look at what I've got here. It works as far as I can tell. It'll do to make a bigger one from. It's such old stuff I wasn't sure I could make a generator. But I did."

He showed McGuire the device. It was a trigger-energy field generator, a development from the electrets of ancient days which stored a bound charge of electricity in a mixture of waxes so that it could not be short circuited and could only be released by the melting of the electret wax.

The trigger-energy field stored latent energy in the molecules of any substance at all. Stored, it remained only latent until released by special conditions, when it usually appeared as heat. There was a time when there were great hopes of using it for metal-casting.

Sufficient latent energy for the melting of a billet of metal could be stored in the metal, and the metal remained cold and could be handled in any way as long as the latent—trigger—energy remained bound.

But when it was released the metal melted from its own stored trigger-energy. Inability to control the temperature the melted metal would reach had made it impractical for casting and it had never had an actual industrial application.

"The point is," Tom told McGuire, "that borderline matter or stuff on the thin edge of being real can penetrate our matter without being disturbed. A plane flew through that globe over the polo field and nothing happened.

"But if the plane had been charged up with trigger-energy as its charged molecules encountered the uncharged molecules of ghost-matter they'd have to discharge. The latent energy would go to the ghost matter molecules.

"But since energy can't leave this cosmos the ghost-matter molecules would come into our space and become real—and since matter can only enter our cosmos if other matter leaves it the discharged molecules would go into the other cosmos.

"In other words I think a plane charged with trigger-energy flying into a globe would turn to ghost-matter and an exactly equal amount of ghost-matter would turn real, atom for atom and molecule for molecule. Here's the math."

McGuire checked carefully, and then began to pace up and down the laboratory. "It looks right," he said. He said uneasily, "If the Government got hold of this, there'd be atomic bombs charged with trigger-energy. Dropped on the Ghost Planet they'd become that other kind of matter and explode there."

"Undoubtedly," said Tom, "They could do the same to us. We're ghosts to them as they're ghosts to us."

"I've got to think," said McGuire abruptly.

"I," admitted Tom, "could do with some sleep."

He went out, stumbling a little, and had to ask a servant where he was supposed to sleep. On the way he saw Lan and Kit. They were walking together in the garden and Lan was in the middle of some enthusiastic explanation.

He was immaculate and the sunlight glinted on his hair. He made a graceful gesture and put his hand on Kit's shoulder. She looked up at him and smiled and then saw Tom.

"How's it going, Tom?" She called eagerly.

"Got some stuff designed," said Tom and yawned. "Your father's working on it now."

He went on wearily to the quarters assigned to him and to Lan together. He saw himself in a mirror. His clothes were wilted and rumpled, his hair hopelessly uncombed. His eyes were red from strain and altogether he was not a pretty sight. Compared to Lan—He surveyed himself for a moment.

"Oh, the heck with it!" he growled. He lay down and was instantly asleep.

The newscasters had a busy evening, while he slept. There were interviews with eyewitnesses of the Cleveland seizure of Arthur V. Handmetter and a broadcast of astronomical motion-pictures of the Ghost Planet. There were reenactments of a seizure or kidnapping in Chungking.

There were announcements by the heads of the official Government astronomical research project, who managed to put into their discussions of the "comet"—they carefully said nothing significant—plugs for more money for their staffs and equipment. Essentially, these officials said that the "comet" was simply gas in so attenuated a form that if it were condensed to the thickness of air at sea level on Earth it would all go into a two-quart bottle.

But there was a tight-beam vision cast from the Moon observatory which confirmed the fact that a steady stream of thousand-foot globes of mist moved from the "comet"——the Ghost Planet—to Earth and back again.

And it confirmed, too, the fact that seven returning globes were enormously more dense than any globes leaving the "comet" for Earth, as if they had somehow absorbed or eaten some substance on Earth.

Since at least two humans were known to have been carried away from large cities, it was reasonable to assume that five other isolated individuals might have been taken away without any eyewitnesses.

Then an eminent psychiatrist appeared on the screen and beamed at his audience, and jovially assured them that mass illusions were commonplace. He listed examples going all the way back to the sworn statements of crowds that they had seen witches riding on broomsticks.

He instanced a craze of flying disks, whose appearance was sworn to by wholly credible witnesses and he referred humorously to the craze of a few years before. Then a meteor shower had been interpreted as the arrival of a flight of space-ships from somewhere and for months afterward honest men and women reported seeing stilt-legged green men in various unlikely places. But all were illusions.

"Illusion is a form of catharsis," said the psychiatrist reassuringly. "We objectify our fears. We picture them outside of ourselves and so consider that we get rid of them. I do not doubt that people in Chungking and Cleveland believe they saw everything they report. I merely say that mass suggestibility makes it possible for a large number of people to share a common illusion."

Human beings being what they are and psychiatry being a very obscure science, this vision cast tended to reassure everybody who did not stop to reflect that vision cast screens portrayed the globes and the Ghost Planet and that illusions which affect electronic devices are not illusions.

But the newscast went on to show one of the world's most glamorous actresses at a famous resort where she was honeymooning with her seventh husband. There was an appealing sequence of a small white dog lying on his master's grave with the explanation that he refused to leave it.

There was a picture of an important political figure leaving the World White House. A festival of flowers in Rio. The coming of the puffins to Greenland. A minor eruption of a volcano in the Galapagos.

In short the matter of the Ghost Planet was honestly presented as the big news feature of the day and then was deftly played down. Ex-President McGuire's broadcast of the night before, assuring the public that there was real information available about the Ghost Planet, was not referred to at all.

Kit was angered by that. She told Lan indignantly that her father's political enemies were refusing him a hearing for fear that the disclosure of his rightness and their wrongness would cause a political repercussion.

"Oh, of course," said Lan sagely. "My Guild was opposed to him, you know. I was suspended, really, because I'm engaged to you. That's why I can't get a job."

Kit regarded him with warm admiration for his martyrdom. "You'll show them!" she said vengefully. "When you show them what you can do."

Then Lan told her tenderly that she filled all his mind and it was hard to think of anything but her. But he did have the beginning of an idea for an interstellar drive. It would probably take some months of research to develop it and he could not put his whole mind on it while fearing that something might happen to break their engagement.

But then he began to picture the idyllic situation which would arise if they were married even if it were an elopement—and he carried on his research with her to inspire him to brilliance. He did not mention the fact that, as he had no job, their support as well as the financing of his research would have to be at her father's charge.

That was left for Kit to resolve upon for herself. Lan grew lyrical about the genius which would come to him immediately they were married. It appeared that, in sheer dutifulness to her father, she should elope with Lan immediately.

When Tom awoke next morning, McGuire was grimly at work in his laboratory. The model trigger-energy field generator had been a necessary preliminary to later work, because trigger-energy had no regular practical use and few physicists had ever seen a generator of the field.

McGuire had studied it and spent the night in grim and somewhat clumsy labor upon a much larger one. When Tom examined it he realized that sound engineering had made up for lack of dexterity. This generator might be the largest that had ever been built and undoubtedly it would work.

"I asked your friend Lan to help me install this," said McGuire savagely, "and he explained very plausibly that Kit had asked him to go in to Pasadena with her and said regretfully that he would ask her to excuse him. He didn't have the least idea what this was!"

Tom said, "It's pretty old-fashioned, sir. I remembered it because I'm always digging in outdated textbooks. There's fascinating stuff in them. I suspect there are a lot of useful leads in forgotten facts that simply weren't followed up when they were first discovered."

McGuire grunted. "Nevertheless, your friend is simply planning a career as my son-in-law. That's all! Shall we install this on the ship?"

Tom postponed breakfast to get at it. Presently the two of them staggered out of the laboratory to the Weddington with their load. The little emergency-ship was small enough and clumsy enough and ugly enough to have no attraction for a wealthy amateur who wanted to do space flying for a thrill. That was why McGuire had been able to get hold of it. The job of the moment wasn't glamorous either.

There were some people—probably Lan among them—who would have been startled to see a former chief executive of the World Government helping to carry out a weighty clumsy device and working with grunts and heavings to get it into place against an ungainly small ship's nose, then sweating as he worked a welder—sometimes he merely held the braces in place while Tom welded them—to fasten it on.

McGuire, sweat-streaked and dirty, was making the last electric connections when the groundcar came whizzing up the drive and stopped with a squealing of brakes. Kit was very pale. Lan looked at once uneasy and excited—but more uneasy.

"Something's happening in Pasadena," he said, and gulped. "There are four globes there. One of them's squatted over the General Hospital. There are three others linked to it. All four are getting denser by the minute. As if"—he gulped—"as if they were eating the people inside."

Kit got out of the car. Her knees wobbled.

"I—made Lan come back," she whispered. "They're—eating the people. Lan says so."

McGuire painstakingly climbed down the ladder. He threw it aside. Tom was in the act of wrenching open the entrance port of the Weddington. He climbed inside. McGuire followed. A deep droning noise sounded, so deep and so heavy that it seemed to shake the very ground. Then there sounded a throbbing noise and the Weddington moved straight up. But as it rose it headed toward Pasadena.

CHAPTER VI

Panic in Pasadena

There was ungodly panic in Pasadena. It was ten A.M., a time when shopping would hardly have begun and the industries of the cities should have emptied the streets of men. But as the Weddington came clumsily toward the city its ways were black with fleeing humanity.

For once the moving sidewalks were so crowded that passengers were edged off, reeling, into the throngs which fought to get on. Ground vehicles—trucks and commercial vehicles almost exclusively—blared and roared their sirens among crowds afoot which had overflowed into the vehicular ways. All of Pasadena struggled furiously to get from where it was to somewhere else. Mostly, to be sure, men battled to reach their families and mothers ran desperately to the schools to relieve their children.

From aloft, it seemed that the streets simply boiled with black figures, eddying purposelessly, and that only relatively small streams of fugitives trickled from the streets at the edges of the city and fled for the open country.

The buildings of the city were unchanged. The tall block-shaped structures which alone were economical enough to build for rental to any but the rich stood serene. Untroubled small wisps of steam drifted from their tops in the morning sunlight.

But there was one oddity which accounted for everything that was strange among the people. Above a group of buildings set in green lawns an alien and frightening appearance hung. At first, from the Weddington, Tom Drake saw only the top three monstrous globes. They were smoky. They looked thick. But they did not yet look solid.

Touching each other as the upper part of a colossal inverted pyramid, they also touched a fourth globe which touched the ground. Buildings vanished into its dark murkiness. It enclosed the major part of the town's principal hospital.

The Weddington flew clumsily, like a wingless beetle, making a monstrous throbbing in the air. It wabbled in its flight. It fishtailed and seemed sometimes to progress crabwise. It was not designed for flight in atmosphere and the new excresence on its bow ruined what streamlining it may have had. It was hopelessly unhandy in the air. But it flew toward Pasadena and wallowed to a lower level and went droning heavily toward the fifteen-hundred-foot pile of smoky spheres.

It blundered into the first of them. All four were growing momentarily thicker and less transparent but still the Weddington—by the precedent of planes which had flown through other spheres—should have penetrated it without difficulty.

It did penetrate. But there was a mark where it struck. An instant later it bounced out crazily at an angle to its original course, spinning like a top and making lunatic darts in every direction successively. It had encountered resistance.

It was two thousand feet up and still gyrating unpredictably when Tom crawled back to the control seat. He had been thrown furiously to one side when the ship hit a spongy obstacle. There was a cut on his temple which bled messily down his cheek. McGuire held fast to stanchions beside a vision port and stared out.

"Lucky!" panted Tom. "I just put a trace of power in the trigger-field. If I'd given it full power we'd have been wrecked. Why can't I have sense? We were trying to make it solid ahead of us! Ahead!"

He straightened out the Weddington with the gyros. He swung in midair and dived again.

"This time," he panted, "we'll hurt them! I don't know how badly, but we'll hurt! The thing's working! We charge up air with trigger-energy. When it hits ghost-matter, it substitutes—air for metal, most likely.

"Since it's a matter of mass, that makes a vacuum which draws more trigger-charged air to substitute for more ghost metal. Hitting it head on was like trying to push a boat through water its bow turns to ice. This time, though—"

He leveled the Weddington out. He shot at the chosen globe. The clumsy space-craft throbbed and roared. A hundred yards from it, Tom's fingers moved like lightning. The throbbing ceased instantly. The Weddington began to arch downward. And then it spun upon its own axis in midair, turned end for end and vanished into the murky globe backward.

"We'll leave solid stuff behind us now!" gasped Tom. "Hold fast!"

For seconds the little craft plunged through darkness. The globes were dark as black smoke. There was nothing at all to be seen. Then there was light, and Tom's fingers flashed again, and the Weddington climbed frantically for the sky, precariously close to the tops of buildings rearing up beyond the hospital.

McGuire said in deep satisfaction, "Nicked him! Not bad at all!"

The spots where the Weddington had dived into and left the globe were plainly visible. The trigger-energy field had trailed behind the ship, this time, as it shot through the ghost-globe. And this time Tom had put full power into the field. Borderline matter materialized as matter of this cosmos and air—only air—replaced it in the universe of the ghost-ships.

Irregularly shaped slabs of solid stuff, exchanged for thin air, became quite real in this universe and fell crashing through the unsubstantiality of which it had been a part. A complete tunnel of clear air led through the globe where the Weddington had pierced it. Because what had been ghost stuff had become real, and no ghost metal but only ghost air had replaced it.

"That'll be a wallop!" said Tom as the little ship climbed. "A few more punctures and they'll know they're hurt!"

He reached the top of the necessary climb and dived again. But as the Weddington went roaring downward for further battle, the sphere at which he aimed shot skyward. It was very dense now. Certainly human beings, and possibly other matter of this earth had gone nearer to the borderline of ghostliness.

Patients had become partly unreal. As a necessary consequence the four globes had become very slightly real. And they were vulnerable to the Weddington. The clumsy little ship was a deadly weapon to them—though only where there was atmosphere or other substance to trade for the matter of the ghost-ships' hulls.

One fled. A second detached itself from the others and shot up for the heavens. Tom swerved the Weddington—dived more steeply—and the third of the upper globes fled before it.

Then, from openings in the hull of the remaining murky mass, small murky objects shot out. They soared away, and were suddenly snatched by invisible forces and drawn with enormous acceleration after the three fleeing ships.

Later Tom and McGuire agreed that these smaller objects were crew members of the crippled ghost vessel. It was still a ghost. It was still not more dense than dense black smoke and it still enclosed a major part of the hospital.

Possibly, in their dive through it, the two men had damaged some essential control or drive mechanism. And Tom guessed that the crew which dived out of the crippled vessel had been snatched by tractor beams in the escaping ships.

But at the moment that did not matter. One ghost-ship, dark and well on the way to reality yet still penetrable by normal matter, remained huddled over the hospital building. The raid—if it was a raid—had been at least partly frustrated. But the Weddington had been wrongly equipped when the trigger-energy generator was mounted on its bow.

There were other things to be done. Tom headed it back toward its starting place while he and McGuire canvassed the situation as of the moment. McGuire was very hopeful. It was Tom who was the gloomy one.

"I don't think much can be learned from the ship that was left behind," he said cynically. "If I know the sort of people who'll be in charge in Pasadena you'd have to spend hours getting permission to try to examine it.