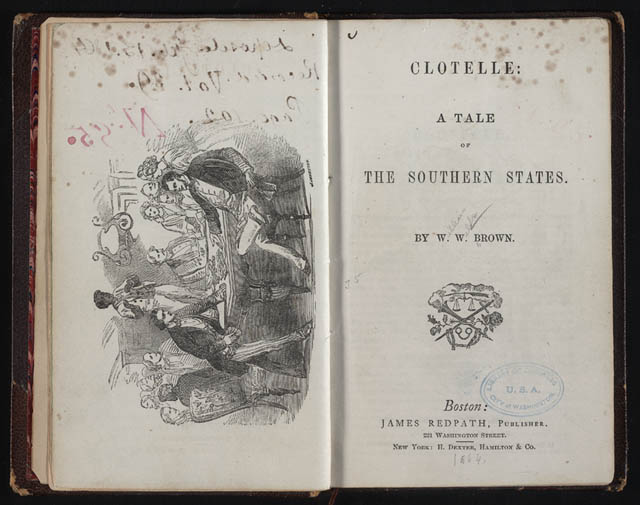

CLOTELLE:

A TALE OF THE SOUTHERN STATES

by

William Wells Brown

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

THE SLAVE'S SOCIAL CIRCLE.

With the growing population in the Southern States, the increase of

mulattoes has been very great. Society does not frown upon the man who

sits with his half-white child upon his knee whilst the mother stands,

a slave, behind his chair. In nearly all the cities and towns of the

Slave States, the real negro, or clear black, does not amount to more

than one in four of the slave population. This fact is of itself the

best evidence of the degraded and immoral condition of the relation of

master and slave. Throughout the Southern States, there is a class of

slaves who, in most of the towns, are permitted to hire their time from

their owners, and who are always expected to pay a high price. This

class is the mulatto women, distinguished for their fascinating beauty.

The handsomest of these usually pay the greatest amount for their time.

Many of these women are the favorites of men of property and standing,

who furnish them with the means of compensating their owners, and not a

few are dressed in the most extravagant manner.

When we take into consideration the fact that no safeguard is thrown

around virtue, and no inducement held out to slave-women to be pure and

chaste, we will not be surprised when told that immorality and vice

pervade the cities and towns of the South to an extent unknown in the

Northern States. Indeed, many of the slave-women have no higher

aspiration than that of becoming the finely-dressed mistress of some

white man. At negro balls and parties, this class of women usually make

the most splendid appearance, and are eagerly sought after in the

dance, or to entertain in the drawing-room or at the table.

A few years ago, among the many slave-women in Richmond, Virginia, who

hired their time of their masters, was Agnes, a mulatto owned by John

Graves, Esq., and who might be heard boasting that she was the

daughter of an American Senator. Although nearly forty years of age at

the time of which we write, Agnes was still exceedingly handsome. More

than half white, with long black hair and deep blue eyes, no one felt

like disputing with her when she urged her claim to her relationship

with the Anglo-Saxon.

In her younger days, Agnes had been a housekeeper for a young

slaveholder, and in sustaining this relation had become the mother of

two daughters. After being cast aside by this young man, the

slave-woman betook herself to the business of a laundress, and was

considered to be the most tasteful woman in Richmond at her vocation.

Isabella and Marion, the two daughters of Agnes, resided with their

mother, and gave her what aid they could in her business. The mother,

however, was very choice of her daughters, and would allow them to

perform no labor that would militate against their lady-like

appearance. Agnes early resolved to bring up her daughters as ladies,

as she termed it.

As the girls grew older, the mother had to pay a stipulated price for

them per month. Her notoriety as a laundress of the first class enabled

her to put an extra charge upon the linen that passed through her

hands; and although she imposed little or no work upon her daughters,

she was enabled to live in comparative luxury and have her daughters

dressed to attract attention, especially at the negro balls and parties.

Although the term "negro ball" is applied to these gatherings, yet a

large portion of the men who attend them are whites. Negro balls and

parties in the Southern States, especially in the cities and towns, are

usually made up of quadroon women, a few negro men, and any number of

white gentlemen. These are gatherings of the most democratic character.

Bankers, merchants, lawyers, doctors, and their clerks and students,

all take part in these social assemblies upon terms of perfect

equality. The father and son not unfrequently meet and dance alike at a

negro ball.

It was at one of these parties that Henry Linwood, the son of a wealthy

and retired gentleman of Richmond, was first introduced to Isabella,

the oldest daughter of Agnes. The young man had just returned from

Harvard College, where he had spent the previous five years. Isabella

was in her eighteenth year, and was admitted by all who knew her to be

the handsomest girl, colored or white, in the city. On this occasion,

she was attired in a sky-blue silk dress, with deep black lace

flounces, and bertha of the same. On her well-moulded arms she wore

massive gold bracelets, while her rich black hair was arranged at the

back in broad basket plaits, ornamented with pearls, and the front in

the French style (a la Imperatrice), which suited her classic face to

perfection.

Marion was scarcely less richly dressed than her sister.

Henry Linwood paid great attention to Isabella which was looked upon

with gratification by her mother, and became a matter of general

conversation with all present. Of course, the young man escorted the

beautiful quadroon home that evening, and became the favorite visitor

at the house of Agnes. It was on a beautiful moonlight night in the

month of August when all who reside in tropical climates are eagerly

grasping for a breath of fresh air, that Henry Linwood was in the

garden which surrounded Agnes' cottage, with the young quadroon by his

side. He drew from his pocket a newspaper wet from the press, and read

the following advertisement:—

NOTICE.—Seventy-nine negroes will be offered for sale on Monday,

September 10, at 12 o'clock, being the entire stock of the late John

Graves in an excellent condition, and all warranted against the common

vices. Among them are several mechanics, able-bodied field-hands,

plough-boys, and women with children, some of them very prolific,

affording a rare opportunity for any one who wishes to raise a strong

and healthy lot of servants for their own use. Also several mulatto

girls of rare personal qualities,—two of these very superior.

Among the above slaves advertised for sale were Agnes and her two

daughters. Ere young Linwood left the quadroon that evening, he

promised her that he would become her purchaser, and make her free and

her own mistress.

Mr. Graves had long been considered not only an excellent and upright

citizen of the first standing among the whites, but even the slaves

regarded him as one of the kindest of masters. Having inherited his

slaves with the rest of his property, he became possessed of them

without any consultation or wish of his own. He would neither buy nor

sell slaves, and was exceedingly careful, in letting them out, that

they did not find oppressive and tyrannical masters. No slave

speculator ever dared to cross the threshold of this planter of the Old

Dominion. He was a constant attendant upon religious worship, and was

noted for his general benevolence. The American Bible Society, the

American Tract Society, and the cause of Foreign Missions, found in him

a liberal friend. He was always anxious that his slaves should appear

well on the Sabbath, and have an opportunity of hearing the word of God.

CHAPTER II

THE NEGRO SALE.

As might have been expected, the day of sale brought an usually large

number together to compete for the property to be sold. Farmers, who

make a business of raising slaves for the market, were there, and

slave-traders, who make a business of buying human beings in the

slave-raising States and taking them to the far South, were also in

attendance. Men and women, too, who wished to purchase for their own

use, had found their way to the slave sale.

In the midst of the throne was one who felt a deeper interest in the

result of the sale than any other of the bystanders. This was young

Linwood. True to his promise, he was there with a blank bank-check in

his pocket, awaiting with impatience to enter the list as a bidder for

the beautiful slave.

It was indeed a heart-rending scene to witness the lamentations of

these slaves, all of whom had grown up together on the old homestead of

Mr. Graves, and who had been treated with great kindness by that

gentleman, during his life. Now they were to be separated, and form new

relations and companions. Such is the precarious condition of the

slave. Even when with a good master, there is no certainty of his

happiness in the future.

The less valuable slaves were first placed upon the auction-block, one

after another, and sold to the highest bidder. Husbands and wives were

separated with a degree of indifference that is unknown in any other

relation in life. Brothers and sisters were tom from each other, and

mothers saw their children for the last time on earth.

It was late in the day, and when the greatest number of persons were

thought to be present, when Agnes and her daughters were brought out to

the place of sale. The mother was first put upon the auction-block, and

sold to a noted negro trader named Jennings. Marion was next ordered to

ascend the stand, which she did with a trembling step, and was sold for

$1200.

All eyes were now turned on Isabella, as she was led forward by the

auctioneer. The appearance of the handsome quadroon caused a deep

sensation among the crowd. There she stood, with a skin as fair as most

white women, her features as beautifully regular as any of her sex of

pure Anglo-Saxon blood, her long black hair done up in the neatest

manner, her form tall and graceful, and her whole appearance indicating

one superior to her condition.

The auctioneer commenced by saying that Miss Isabella was fit to deck

the drawing-room of the finest mansion in Virginia.

"How much, gentlemen, for this real Albino!—fit fancy-girl for any

one! She enjoys good health, and has a sweet temper. How much do you

say?"

"Five hundred dollars."

"Only five hundred for such a girl as this? Gentlemen, she is worth a

deal more than that sum. You certainly do not know the value of the

article you are bidding on. Here, gentlemen, I hold in my hand a paper

certifying that she has a good moral character."

"Seven hundred."

"Ah, gentlemen, that is something like. This paper also states that she

is very intelligent."

"Eight hundred."

"She was first sprinkled, then immersed, and is now warranted to be a

devoted Christian, and perfectly trustworthy."

"Nine hundred dollars."

"Nine hundred and fifty."

"One thousand."

"Eleven hundred."

Here the bidding came to a dead stand. The auctioneer stopped, looked

around, and began in a rough manner to relate some anecdote connected

with the sale of slaves, which he said had come under his own

observation.

At this juncture the scene was indeed a most striking one. The

laughing, joking, swearing, smoking, spitting, and talking, kept up a

continual hum and confusion among the crowd, while the slave-girl stood

with tearful eyes, looking alternately at her mother and sister and

toward the young man whom she hoped would become her purchaser.

"The chastity of this girl," now continued the auctioneer, "is pure.

She has never been from under her mother's care. She is virtuous, and

as gentle as a dove."

The bids here took a fresh start, and went on until $1800 was reached.

The auctioneer once more resorted to his jokes, and concluded by

assuring the company that Isabella was not only pious, but that she

could make an excellent prayer.

"Nineteen hundred dollars."

"Two thousand."

This was the last bid, and the quadroon girl was struck off, and became

the property of Henry Linwood.

This was a Virginia slave-auction, at which the bones, sinews, blood,

and nerves of a young girl of eighteen were sold for $500; her moral

character for $200; her superior intellect for $100; the benefits

supposed to accrue from her having been sprinkled and immersed,

together with a warranty of her devoted Christianity, for $300; her

ability to make a good prayer for $200; and her chastity for $700 more.

This, too, in a city thronged with churches, whose tall spires look

like so many signals pointing to heaven, but whose ministers preach

that slavery a God-ordained institution!

The slaves were speedily separated, and taken along by their respective

masters. Jennings, the slave-speculator, who had purchased Agnes and

her daughter Marion, with several of the other slaves, took them to the

county prison, where he usually kept his human cattle after purchasing

them, previous to starting for the New Orleans market.

Linwood had already provided a place for Isabella, to which she was

taken. The most trying moment for her was when she took leave of her

mother and sister. The "Good-by" of the slave is unlike that of any

other class in the community. It is indeed a farewell forever. With

tears streaming down their cheeks, they embraced and commanded each

other to God, who is no respecter of persons, and before whom master

and slave must one day appear.

CHAPTER III

THE SLAVE SPECULATOR.

Dick Jennings the slave-speculator, was one of the few Northern men,

who go to the South and throw aside their honest mode of obtaining a

living and resort to trading in human beings. A more repulsive looking

person could scarcely be found in any community of bad looking men.

Tall, lean and lank, with high cheek-bones, face much pitted with the

small-pox, gray eyes with red eyebrows, and sandy whiskers, he indeed

stood alone without mate or fellow in looks. Jennings prided himself

upon what he called his goodness of heart and was always speaking of

his humanity. As many of the slaves whom he intended taking to the New

Orleans market had been raised in Richmond, and had relations there, he

determined to leave the city early in the morning, so as not to witness

any of the scenes so common the departure of a slave-gang to the far

South. In this, he was most successful; for not even Isabella, who had

called at the prison several times to see her mother and sister, was

aware of the time that they were to leave.

The slave-trader started at early dawn, and was beyond the confines of

the city long before the citizens were out of their beds. As a slave

regards a life on the sugar, cotton, or rice plantation as even worse

than death, they are ever on the watch for an opportunity to escape.

The trader, aware of this, secures his victims in chains before he sets

out on his journey. On this occasion, Jennings had the men chained in

pairs, while the women were allowed to go unfastened, but were closely

watched.

After a march of eight days, the company arrived on the banks of the

Ohio River, where they took a steamer for the place of their

destination. Jennings had already advertised in the New Orleans papers,

that he would be there with a prime lot of able-bodied slaves, men and

women, fit for field-service, with a few extra ones calculated for

house servants,—all between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five years;

but like most men who make a business of speculating in human beings,

he often bought many who were far advanced in years, and would try to

pass them off for five or six years younger than they were. Few persons

can arrive at anything approaching the real age of the negro, by mere

observation, unless they are well acquainted with the race. Therefore,

the slave-trader frequently carried out the deception with perfect

impunity.

After the steamer had left the wharf and was fairly out on the bosom of

the broad Mississippi, the speculator called his servant Pompey to him;

and instructed him as to getting the negroes ready for market. Among

the forty slaves that the trader had on this occasion, were some whose

appearance indicated that they had seen some years and had gone through

considerable service. Their gray hair and whiskers at once pronounced

them to be above the ages set down in the trader's advertisement.

Pompey had long been with Jennings, and understood his business well,

and if he did not take delight in the discharge of his duty, he did it

at least with a degree of alacrity, so that he might receive the

approbation of his master.

Pomp, as he was usually called by the trader, was of real negro blood,

and would often say, when alluding to himself, "Dis nigger am no

counterfeit, he is de ginuine artikle. Dis chile is none of your

haf-and-haf, dere is no bogus about him."

Pompey was of low stature, round face, and, like most of his race, had

a set of teeth, which, for whiteness and beauty, could not be

surpassed; his eyes were large, lips thick, and hair short and woolly.

Pompey had been with Jennings so long, and had seen so much of buying

and selling of his fellow-creatures, that he appeared perfectly

indifferent to the heart-rending scenes which daily occurred in his

presence. Such is the force of habit:—

"Vice is a monster of such frightful mien,

That to be hated, needs but to be seen;

But seen too oft, familiar with Its face,

We first endure, then pity, then embrace."

It was on the second day of the steamer's voyage, that Pompey selected

five of the oldest slaves, took them into a room by themselves, and

commenced preparing them for the market.

"Now," said he, addressing himself to the company, "I is de chap dat is

to get you ready for de Orleans market, so dat you will bring marser a

good price. How old is you?" addressing himself to a man not less than

forty.

"If I live to see next sweet-potato-digging time, I shall be either

forty or forty-five, I don't know which."

"Dat may be," replied Pompey; "but now you is only thirty years

old,—dat's what marser says you is to be."

"I know I is more den dat," responded the man.

"I can't help nuffin' about dat," returned Pompey; "but when you get

into de market and any one ax you how old you is, and you tell um you

is forty or forty-five, marser will tie you up and cut you all to

pieces. But if you tell urn dat you is only thirty, den he won't. Now

remember dat you is thirty years old and no more."

"Well den, I guess I will only be thirty when dey ax me."

"What's your name?" said Pompey, addressing himself to another.

"Jeems."

"Oh! Uncle Jim, is it?"

"Yes."

"Den you must have all them gray whiskers shaved off, and all dem gray

hairs plucked out of your head." This was all said by Pompey in a

manner which showed that he know what he was about.

"How old is you?" asked Pompey of a tall, strong-looking man. "What's

your name?"

"I am twenty-nine years old, and my name is Tobias, but they calls me

Toby."

"Well, Toby, or Mr. Tobias, if dat will suit you better, you are now

twenty-three years old; dat's all,—do you understand dat?"

"Yes," replied Toby.

Pompey now gave them all to understand how old they were to be when

asked by persons who were likely to purchase, and then went and

reported to his master that the old boys were all right.

"Be sure," said Jennings, "that the niggers don't forget what you have

taught them, for our luck this time in the market depends upon their

appearance. If any of them have so many gray hairs that you cannot

pluck them out, take the blacking and brush, and go at them."

CHAPTER IV

THE BOAT-RACE.

At eight o'clock, on the evening of the third day of the passage, the

lights of another steamer were soon in the distance, and apparently

coming up very fast. This was the signal for a general commotion on

board the Patriot, and everything indicated that a steamboat-race was

at hand. Nothing can exceed the excitement attendant upon the racing of

steamers on the Mississippi.

By the time the boats had reached Memphis they were side by side, and

each exerting itself to get in advance of the other. The night was

clear, the moon shining brightly, and the boats so near to each other

that the passengers were within speaking distance. On board the Patriot

the firemen were using oil, lard, butter, and even bacon, with woody

for the purpose of raising the steam to its highest pitch. The blaze

mingled with the black smoke that issued from the pipes of the other

boat, which showed that she also was burning something more combustible

than wood.

The firemen of both boats, who were slaves, were singing songs such as

can only be heard on board a Southern steamer. The boats now came

abreast of each other, and nearer and nearer, until they were locked so

that men could pass from one to the other. The wildest excitement

prevailed among the men employed on the steamers, in which the

passengers freely participated.

The Patriot now stopped to take in passengers, but still no steam was

permitted to escape. On the starting of the boat again, cold water was

forced into the boilers by the feed-pumps, and, as might have been

expected, one of the boilers exploded with terrific force, carrying

away the boiler-deck and tearing to pieces much of the machinery. One

dense fog of steam filled every part of the vessel, while shrieks,

groans, and cries were heard on every side. Men were running hither and

thither looking for their wives, and women wore flying about in the

wildest confusion seeking for their husbands. Dismay appeared on every

countenance.

The saloons and cabins soon looked more like hospitals than anything

else; but by this time the Patriot had drifted to the shore, and the

other steamer had come alongside to render assistance to the disabled

boat. The killed and wounded (nineteen in number) were put on shore,

and the Patriot, taken in tow by the Washington, was once more on her

journey.

It was half-past twelve, and the passengers, instead of retiring to

their berths, once more assembled at the gambling-tables. The practice

of gambling on the western waters has long been a source of annoyance

to the more moral persons who travel on our great rivers. Thousands of

dollars often change owners during a passage from St. Louis or

Louisville to New Orleans, on a Mississippi steamer. Many men are

completely ruined on such occasions, and duels are often the

consequence.

"Go call my boy, steward," said Mr. Jones, as he took his cards one by

one from the table.

In a few minutes a fine-looking, bright-eyed mulatto boy, apparently

about sixteen years of age, was standing by his master's side at the

table.

"I am broke, all but my boy," said Jones, as he ran his fingers through

his cards; "but he is worth a thousand dollars, and I will bet the half

of him."

"I will call you," said Thompson, as he laid five hundred dollars at

the feet of the boy, who was standing, on the table, and at the same

time throwing down his cards before his adversary.

"You have beaten me," said Jones; and a roar of laughter followed from

the other gentleman as poor Joe stepped down from the table.

"Well, I suppose I owe you half the nigger," said Thompson, as he took

hold of Joe and began examining his limbs.

"Yes," replied Jones, "he is half yours. Let me have five hundred

dollars, and I will give you a bill of sale of the boy."

"Go back to your bed," said Thompson to his chattel, "and remember that

you now belong to me."

The poor slave wiped the tears from his eyes, as, in obedience, he

turned to leave the table.

"My father gave me that boy," said Jones, as he took the money, "and I

hope, Mr. Thompson, that you will allow me to redeem him."

"Most certainly, Sir," replied Thompson. "Whenever you hand over the

cool thousand the negro is yours."

Next morning, as the passengers were assembling in the cabin and on

deck and while the slaves were running about waiting on or looking for

their masters, poor Joe was seen entering his new master's stateroom,

boots in hand.

"Who do you belong to?" inquired a gentleman of an old negro, who

passed along leading a fine Newfoundland dog which he had been feeding.

"When I went to sleep las' night," replied the slave, "I 'longed to

Massa Carr; but he bin gamblin' all night an' I don't know who I 'longs

to dis mornin'."

Such is the uncertainty of a slave's life. He goes to bed at night the

pampered servant of his young master, with whom he has played in

childhood, and who would not see his slave abused under any

consideration, and gets up in the morning the property of a man whom he

has never before seen.

To behold five or six tables in the saloon of a steamer, with half a

dozen men playing cards at each, with money, pistols, and bowie-knives

spread in splendid confusion before them, is an ordinary thing on the

Mississippi River.

CHAPTER V

THE YOUNG MOTHER.

On the fourth morning, the Patriot landed at Grand Gulf, a beautiful

town on the left bank of the Mississippi. Among the numerous passengers

who came on board at Rodney was another slave-trader, with nine human

chattels which he was conveying to the Southern market. The passengers,

both ladies and gentlemen, were startled at seeing among the new lot of

slaves a woman so white as not to be distinguishable from the other

white women on board. She had in her arms a child so white that no one

would suppose a drop of African blood flowed through its blue veins.

No one could behold that mother with her helpless babe, without feeling

that God would punish the oppressor. There she sat, with an expressive

and intellectual forehead, and a countenance full of dignity and

heroism, her dark golden locks rolled back from her almost snow-white

forehead and floating over her swelling bosom. The tears that stood in

her mild blue eyes showed that she was brooding over sorrows and wrongs

that filled her bleeding heart.

The hearts of the passers-by grew softer, while gazing upon that young

mother as she pressed sweet kisses on the sad, smiling lips of the

infant that lay in her lap. The small, dimpled hands of the innocent

creature were slyly hid in the warm bosom on which the little one

nestled. The blood of some proud Southerner, no doubt, flowed through

the veins of that child.

When the boat arrived at Natches, a rather good-looking,

genteel-appearing man came on board to purchase a servant. This

individual introduced himself to Jennings as the Rev. James Wilson. The

slave-trader conducted the preacher to the deck-cabin, where he kept

his slaves, and the man of God, after having some questions answered,

selected Agnes as the one best suited to his service.

It seemed as if poor Marion's heart would break when she found that she

was to be separated from her mother. The preacher, however, appeared to

be but little moved by their sorrow, and took his newly-purchased

victim on shore. Agnes begged him to buy her daughter, but he refused,

on the ground that he had no use for her.

During the remainder of the passage, Marion wept bitterly.

After a ran of a few hours, the boat stopped at Baton Rouge, where an

additional number of passengers were taken on board, among whom were a

number of persons who had been attending the races at that place.

Gambling and drinking were now the order of the day.

The next morning, at ten o'clock, the boat arrived at New Orleans where

the passengers went to their hotels and homes, and the negroes to the

slave-pens.

Lizzie, the white slave-mother, of whom we have already spoken, created

as much of a sensation by the fairness of her complexion and the

alabaster whiteness of her child, when being conveyed on shore at New

Orleans, as she had done when brought on board at Grand Gulf. Every one

that saw her felt that slavery in the Southern States was not confined

to the negro. Many had been taught to think that slavery was a benefit

rather than an injury, and those who were not opposed to the

institution before, now felt that if whites were to become its victims,

it was time at least that some security should be thrown around the

Anglo-Saxon to gave him from this servile and degraded position.

CHAPTER VI

THE SLAVE-MARKET.

Not far from Canal Street, in the city of New Orleans, stands a large

two-story, flat building, surrounded by a stone wall some twelve feet

high, the top of which is covered with bits of glass, and so

constructed as to prevent even the possibility of any one's passing

over it without sustaining great injury. Many of the rooms in this

building resemble the cells of a prison, and in a small apartment near

the "office" are to be seen any number of iron collars, hobbles,

handcuffs, thumbscrews, cowhides, chains, gags, and yokes.

A back-yard, enclosed by a high wall, looks something like the

playground attached to one of our large New England schools, in which

are rows of benches and swings. Attached to the back premises is a

good-sized kitchen, where, at the time of which we write, two old

negresses were at work, stewing, boiling, and baking, and occasionally

wiping the perspiration from their furrowed and swarthy brows.

The slave-trader, Jennings, on his arrival at New Orleans, took up his

quarters here with his gang of human cattle, and the morning after, at

10 o'clock, they were exhibited for sale. First of all came the

beautiful Marion, whose pale countenance and dejected look told how

many sad hours she had passed since parting with her mother at Natchez.

There, too, was a poor woman who had been separated from her husband;

and another woman, whose looks and manners were expressive of deep

anguish, sat by her side. There was "Uncle Jeems," with his whiskers

off, his face shaven clean, and the gray hairs plucked out ready to be

sold for ten years younger than he was. Toby was also there, with his

face shaven and greased, ready for inspection.

The examination commenced, and was carried on in such a manner as to

shock the feelings of anyone not entirely devoid of the milk of human

kindness.

"What are you wiping your eyes for?" inquired a fat, red-faced man,

with a white hat set on one side of his head and a cigar in his mouth,

of a woman who sat on one of the benches.

"Because I left my man behind."

"Oh, if I buy you, I will furnish you with a better man than you left.

I've got lots of young bucks on my farm."

"I don't want and never will have another man," replied the woman.

"What's your name?" asked a man in a straw hat of a tall negro who

stood with his arms folded across his breast, leaning against the wall.

"My name is Aaron, sar."

"How old are you?"

"Twenty-five."

"Where were you raised?"

"In ole Virginny, sar."

"How many men have owned you?"

"Four."

"Do you enjoy good health?"

"Yes, sar."

"How long did you live with your first owner?"

"Twenty years."

"Did you ever run away?"

"No, sar."

"Did you ever strike your master?"

"No, sar."

"Were you ever whipped much?"

"No, sar; I s'pose I didn't deserve it, sar."

"How long did you live with your second master?"

"Ten years, sar."

"Have you a good appetite?"

"Yes, sar."

"Can you eat your allowance?"

"Yes, sar,—when I can get it."

"Where were you employed in Virginia?"

"I worked de tobacker fiel'."

"In the tobacco field, eh?"

"Yes, sar."

"How old did you say you was?"

"Twenty-five, sar, nex' sweet-'tater-diggin' time."

"I am a cotton-planter, and if I buy you, you will have to work in the

cotton-field. My men pick one hundred and fifty pounds a day, and the

women one hundred and forty pounds; and those who fail to perform their

task receive five stripes for each pound that is wanting. Now, do you

think you could keep up with the rest of the hands?"

"I' don't know sar but I 'specs I'd have to."

"How long did you live with your third master?"

"Three years, sar."

"Why, that makes you thirty-three. I thought you told me you were only

twenty-five?"

Aaron now looked first at the planter, then at the trader, and seemed

perfectly bewildered. He had forgotten the lesson given him by Pompey

relative to his age; and the planter's circuitous questions—doubtless

to find out the slave's real age—had thrown the negro off his guard.

"I must see your back, so as to know how much you have been whipped,

before I think of buying."

Pompey, who had been standing by during the examination, thought that

his services were now required, and, stepping forth with a degree of

officiousness, said to Aaron,—

"Don't you hear de gemman tell you he wants to 'zamin you. Cum,

unharness yo'seff, ole boy, and don't be standin' dar."

Aaron was soon examined, and pronounced "sound;" yet the conflicting

statement about his age was not satisfactory.

Fortunately for Marion, she was spared the pain of undergoing such an

examination. Mr. Cardney, a teller in one of the banks, had just been

married, and wanted a maid-servant for his wife, and, passing through

the market in the early part of the day, was pleased with the young

slave's appearance, and his dwelling the quadroon found a much better

home than often falls to the lot of a slave sold in the New Orleans

market.

CHAPTER VII

THE SLAVE-HOLDING PARSON.

The Rev. James Wilson was a native of the State of Connecticut where he

was educated for the ministry in the Methodist persuasion. His father

was a strict follower of John Wesley, and spared no pains in his son's

education, with the hope that he would one day be as renowned as the

leader of his sect. James had scarcely finished his education at New

Haven, when he was invited by an uncle, then on a visit to his father,

to spend a few months at Natchez in Mississippi. Young Wilson accepted

his uncle's invitation, and accompanied him to the South. Few Young

men, and especially clergymen, going fresh from college to the South,

but are looked upon as geniuses in a small way, and who are not invited

to all the parties in the neighborhood. Mr. Wilson was not an exception

to this rule. The society into which he was thrown, on his arrival at

Natchez, was too brilliant for him not to be captivated by it, and, as

might have been expected, he succeeded in captivating a plantation with

seventy slaves if not the heart of the lady to whom it belonged.

Added to this, he became a popular preacher, and had a large

congregation with a snug salary. Like other planters, Mr. Wilson

confided the care of his farm to Ned Huckelby, an overseer of high

reputation in his way.

The Poplar Farm, as it was called, was situated in a beautiful valley,

nine miles from Natchez, and near the Mississippi River. The once

unshorn face of nature had given way, and the farm now blossomed with a

splendid harvest. The neat cottage stood in a grove, where Lombardy

poplars lift their tops almost to prop the skies, where the willow,

locust and horse-chestnut trees spread forth their branches, and

flowers never ceased to blossom.

This was the parson's country residence, where the family spent only

two months during the year. His town residence was a fine villa, seated

on the brow of a hill at the edge of the city.

It was in the kitchen of this house that Agnes found her new home. Mr.

Wilson was every inch a democrat, and early resolved that "his people,"

as he called his slaves should be well-fed and not over-worked, and

therefore laid down the law and gospel to the overseer as well as to

the slaves. "It is my wish," said he to Mr. Carlingham, an old

school-fellow who was spending a few days with him,—"It is my wish

that a new system be adopted on the plantations in this State. I

believe that the sons of Ham should have the gospel, and I intend that

mine shall have it. The gospel is calculated to make mankind better and

none should be without it."

"What say you," said Carlingham, "about the right of man to his

liberty?"

"Now, Carlingham, you have begun to harp again about men's rights. I

really wish that you could see this matter as I do."'

"I regret that I cannot see eye to eye with you," said Carlingham. "I

am a disciple of Rousseau, and have for years made the rights of man my

study, and I must confess to you that I see no difference between white

and black, as it regards liberty."

"Now, my dear Carlingham, would you really have the negroes enjoy the

same rights as ourselves?"

"I would most certainly. Look at our great Declaration of Independence!

look even at the Constitution of our own Connecticut and see what is

said in these about liberty."

"I regard all this talk about rights as mere humbug. The Bible is older

than the Declaration of Independence, and there I take my stand."

A long discussion followed, in which both gentlemen put forth their

peculiar ideas with much warmth of feeling.

During this conversation, there was another person in the room, seated

by the window, who, although at work, embroidering a fine collar, paid

minute attention to what was said. This was Georgiana, the only

daughter of the parson, who had but just returned from Connecticut,

where she had finished her education. She had had the opportunity of

contrasting the spirit of Christianity and liberty in New England with

that of slavery in her native State, and had learned to feel deeply for

the injured negro. Georgiana was in her nineteenth year, and had been

much benefited by her residence of five years at the North. Her form

was tall and graceful, her features regular and well-defined, and her

complexion was illuminated by the freshness of youth, beauty, and

health.

The daughter differed from both the father and visitor upon the subject

which they had been discussing; and as soon as an opportunity offered,

she gave it as her opinion that the Bible was both the bulwark of

Christianity and of liberty. With a smile she said,—

"Of course, papa will overlook my difference with him, for although I

am a native of the South, I am by education and sympathy a Northerner."

Mr. Wilson laughed, appearing rather pleased than otherwise at the

manner in which his daughter had expressed herself. From this Georgiana

took courage and continued,—

'"Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.' This single passage of

Scripture should cause us to have respect for the rights of the slave.

True Christian love is of an enlarged and disinterested nature. It

loves all who love the Lord Jesus Christ in sincerity, without regard

to color or condition."

"Georgiana, my dear, you are an abolitionist,—your talk is

fanaticism!" said Mr. Wilson, in rather a sharp tone; but the subdued

look of the girl and the presence of Carlingham caused him to soften

his language.

Mr. Wilson having lost his wife by consumption, and Georgiana being his

only child, he loved her too dearly to say more, even if he felt

disposed. A silence followed this exhortation from the young Christian,

but her remarks had done a noble work. The father's heart was touched,

and the sceptic, for the first time, was viewing Christianity in its

true light.

CHAPTER VIII

A NIGHT IN THE PARSON'S KITCHEN.

Besides Agnes, whom Mr. Wilson had purchased from the slave-trader,

Jennings, he kept a number of house-servants. The chief one of these

was Sam, who must be regarded as second only to the parson himself. If

a dinner-party was in contemplation, or any company was to be invited,

after all the arrangements had been talked over by the minister and his

daughter. Sam was sure to be consulted on, the subject by "Miss

Georgy," as Miss Wilson was called by all the servants. If furniture,

crockery, or anything was to be purchased, Sam felt that he had been

slighted if his opinion was not asked. As to the marketing, he did it

all. He sat at the head of the servants' table in the kitchen, and was

master of the ceremonies. A single look from him was enough to silence

any conversation or noise among the servants in the kitchen or in any

other part of the premises.

There is in the Southern States a great amount of prejudice in regard

to color, even among the negroes themselves. The nearer the negro or

mulatto approaches to the white, the more he seems to feel his

superiority over those of a darker hue. This is no doubt the result of

the prejudice that exists on the part of the whites against both the

mulattoes and the blacks.

Sam was originally from Kentucky, and through the instrumentality of

one of his young masters, whom he had to take to school, he had learned

to read so as to be well understood, and, owing to that fact, was

considered a prodigy, not only among his own master's slaves, but also

among those of the town who knew him. Sam had a great wish to follow in

the footsteps of his master and be a poet, and was therefore often

heard singing doggerels of his own composition.

But there was one drawback to Sam, and that was his color. He was one

of the blackest of his race. This he evidently regarded as a great

misfortune; but he endeavored to make up for it in dress. Mr. Wilson

kept his house servants well dressed, and as for Sam, he was seldom

seen except in a ruffled shirt. Indeed, the washerwoman feared him more

than any one else in the house.

Agnes had been inaugurated chief of the kitchen department, and had a

general supervision of the household affairs. Alfred, the coachman,

Peter, and Hetty made up the remainder of the house-servants. Besides

these, Mr. Wilson owned eight slaves who were masons. These worked in

the city. Being mechanics, they were let out to greater advantage than

to keep them on the farm.

Every Sunday evening, Mr. Wilson's servants, including the bricklayers,

assembled in the kitchen, where the events of the week were fully

discussed and commented upon. It was on a Sunday evening, in the month

of June, that there was a party at Mr. Wilson's house, and, according

to custom in the Southern States, the ladies had their maidservants

with them. Tea had been served in "the house," and the servants,

including the strangers, had taken their seats at the table in the

kitchen. Sam, being a "single gentleman," was unusually attentive to

the ladies on this occasion. He seldom let a day pass without spending

an hour or two in combing and brushing his "har." He had an idea that

fresh butter was better for his hair than any other kind of grease, and

therefore on churning days half a pound of butter had always to be

taken out before it was salted. When he wished to appear to great

advantage, he would grease his face to make it "shiny." Therefore, on

the evening of the party, when all the servants were at the table, Sam

cut a big figure. There he sat, with his wool well combed and buttered,

face nicely greased, and his ruffles extending five or six inches from

his bosom. The parson in his drawing-room did not make a more imposing

appearance than did his servant on this occasion.

"I is bin had my fortune tole last Sunday night," said Sam, while

helping one of the girls.

"Indeed!" cried half a dozen voices.

"Yes," continued he; "Aunt Winny tole me I's to hab de prettiest yallah

gal in de town, and dat I's to be free!"

All eyes were immediately turned toward Sally Johnson, who was seated

near Sam.

"I 'specs I see somebody blush at dat remark," said Alfred.

"Pass dem pancakes an' 'lasses up dis way, Mr. Alf, and none ob your

sinuwashuns here," rejoined Sam.

"Dat reminds me," said-Agnes, "dat Dorcas Simpson is gwine to git

married."

"Who to, I want to know?" inquired Peter.

"To one of Mr. Darby's field-hands," answered Agnes.

"I should tink dat gal wouldn't frow herseff away in dat ar way," said

Sally; "She's good lookin' 'nough to git a house-servant, and not hab

to put up wid a field-nigger."

"Yes," said Sam, "dat's a werry unsensible remark ob yourn, Miss Sally.

I admires your judgment werry much, I 'sures you. Dar's plenty ob

susceptible an' well-dressed house-serbants dat a gal ob her looks can

git widout takin' up wid dem common darkies."

The evening's entertainment concluded by Sam relating a little of his

own experience while with his first master, in old Kentucky. This

master was a doctor, and had a large practice among his neighbors,

doctoring both masters and slaves. When Sam was about fifteen years

old, his master set him to grinding up ointment and making pills. As

the young student grew older and became more practised in his

profession, his services were of more importance to the doctor. The

physician having a good business, and a large number of his patients

being slaves,—the most of whom had to call on the doctor when ill,—he

put Sam to bleeding, pulling teeth, and administering medicine to the

slaves. Sam soon acquired the name among the slaves of the "Black

Doctor." With this appellation he was delighted; and no regular

physician could have put on more airs than did the black doctor when

his services were required. In bleeding, he must have more bandages,

and would rub and smack the arm more than the doctor would have thought

of.

Sam was once seen taking out a tooth for one of his patients, and

nothing appeared more amusing. He got the poor fellow down on his back,

and then getting astride of his chest, he applied the turnkeys and

pulled away for dear life. Unfortunately, he had got hold of the wrong

tooth, and the poor man screamed as loud as he could; but it was to no

purpose, for Sam had him fast, and after a pretty severe tussle out

came the sound grinder. The young doctor now saw his mistake, but

consoled himself with the thought that as the wrong tooth was out of

the way, there was more room to get at the right one.

Bleeding and a dose of calomel were always considered indispensable by

the "old boss," and as a matter of course, Sam followed in his

footsteps.

On one occasion the old doctor was ill himself, so as to be unable to

attend to his patients. A slave, with pass in hand, called to receive

medical advice, and the master told Sam to examine him and see what he

wanted. This delighted him beyond measure, for although he had been

acting his part in the way of giving out medicine as the master ordered

it, he had never been called upon by the latter to examine a patient,

and this seemed to convince him after all that he was no sham doctor.

As might have been expected, he cut a rare figure in his first

examination. Placing himself directly opposite his patient, and folding

his arms across his breast, looking very knowingly, he began,—

"What's de matter wid you?"

"I is sick."

"Where is you sick?"

"Here," replied the man, putting his hand upon his stomach.

"Put out your tongue," continued the doctor.

The man ran out his tongue at full length.

"Let me feel your pulse;" at the same time taking his patient's hand in

his, and placing his fingers upon his pulse, he said,—

"Ah! your case is a bad one; ef I don't do something for you, and dat

pretty quick, you'll be a gone coons and dat's sartin."

At this the man appeared frightened, and inquired what was the matter

with him, in answer to which Sam said,

"I done told dat your case is a bad one, and dat's enuff."

On Sam's returning to his master's bedside, the latter said,

"Well, Sam, what do you think is the matter with him?"

"His stomach is out ob order, sar," he replied.

"What do you think had better be done for him?"

"I tink I'd better bleed him and gib him a dose ob calomel," returned

Sam.

So, to the latter's gratification, the master let him have his own way.

On one occasion, when making pills and ointment, Sam made a great

mistake. He got the preparations for both mixed together, so that he

could not legitimately make either. But fearing that if he threw the

stuff away, his master would flog him, and being afraid to inform his

superior of the mistake, he resolved to make the whole batch of pill

and ointment stuff into pills. He well knew that the powder over the

pills would hide the inside, and the fact that most persons shut their

eyes when taking such medicine led the young doctor to feel that all

would be right in the end. Therefore Sam made his pills, boxed them up,

put on the labels, and placed them in a conspicuous position on one of

the shelves.

Sam felt a degree of anxiety about his pills, however. It was a strange

mixture, and he was not certain whether it would kill or cure; but he

was willing that it should be tried. At last the young doctor had his

vanity gratified. Col. Tallen, one of Dr. Saxondale's patients, drove

up one morning, and Sam as usual ran out to the gate to hold the

colonel's horse.

"Call your master," said the colonel; "I will not get out."

The doctor was soon beside the carriage, and inquired about the health

of his patient. After a little consultation, the doctor returned to his

office, took down a box of Sam's new pills, and returned to the

carriage.

"Take two of these every morning and night," said the doctor, "and if

you don't feel relieved, double the dose."

"Good gracious," exclaimed Sam in an undertone, when he heard his

master tell the colonel how to take the pills.

It was several days before Sam could learn the result of his new

medicine. One afternoon, about a fortnight after the colonel's visit

Sam saw his master's patient riding up to the gate on horseback. The

doctor happened to be in the yard, and met the colonel and said,—

"How are you now?"

"I am entirely recovered," replied the patient. "Those pills of yours

put me on my feet the next day."

"I knew they would," rejoined the doctor.

Sam was near enough to hear the conversation, and was delighted beyond

description. The negro immediately ran into the kitchen, amongst his

companions, and commenced dancing.

"What de matter wid you?" inquired the cook.

"I is de greatest doctor in dis country," replied Sam. "Ef you ever get

sick, call on me. No matter what ails you, I is de man dat can cure you

in no time. If you do hab de backache, de rheumaties, de headache, de

coller morbus, fits, er any ting else, Sam is de gentleman dat can put

you on your feet wid his pills."

For a long time after, Sam did little else than boast of his skill as a

doctor.

We have said that the black doctor was full of wit and good sense.

Indeed, in that respect, he had scarcely an equal in the neighborhood.

Although his master resided some little distance out of the city, Sam

was always the first man in all the negro balls and parties in town.

When his master could give him a pass, he went, and when he did not

give him one, he would steal away after his master had retired, and run

the risk of being taken up by the night-watch. Of course, the master

never knew anything of the absence of the servant at night without

permission. As the negroes at these parties tried to excel each other

in the way of dress, Sam was often at a loss to make that appearance

that his heart desired, but his ready wit ever helped him in this. When

his master had retired to bed at night, it was the duty of Sam to put

out the lights, and take out with him his master's clothes and boots,

and leave them in the office until morning, and then black the boots,

brush the clothes, and return them to his master's room.

Having resolved to attend a dress-ball one night, without his master's

permission, and being perplexed for suitable garments, Sam determined

to take his master's. So, dressing himself in the doctor's clothes even

to his boots and hat, off the negro started for the city. Being well

acquainted with the usual walk of the patrols he found no difficulty in

keeping out of their way. As might have been expected, Sam was the

great gun with the ladies that night.

The next morning, Sam was back home long before his master's time for

rising, and the clothes were put in their accustomed place. For a long

time Sam had no difficulty in attiring himself for parties; but the old

proverb that "It is a long lane that has no turning," was verified in

the negro's case. One stormy night, when the rain was descending in

torrents, the doctor heard a rap at his door. It was customary with

him, when called up at night to visit a patient, to ring for Sam. But

this time, the servant was nowhere to be found. The doctor struck a

light and looked for clothes; they too, were gone.—It was twelve

o'clock, and the doctor's clothes, hat, boots, and even his watch, were

nowhere to be found. Here was a pretty dilemma for a doctor to be in.

It was some time before the physician could fit himself out so as to

mike the visit. At last, however, he started with one of the

farm-horses, for Sam had taken the doctor's best saddle-horse. The

doctor felt sure that the negro had robbed him, and was on his way to

Canada; but in this he was mistaken. Sam had gone to the city to attend

a ball, and had decked himself out in his master's best suit. The

physician returned before morning, and again retired to bed but with

little hope of sleep, for his thoughts were with his servant and horse.

At six o'clock, in walked Sam with his master's clothes, and the boots

neatly blacked. The watch was placed on the shelf, and the hat in its

place. Sam had not met any of the servants, and was therefore entirely

ignorant of what had occurred during his absence.

"What have you been about, sir, and where was you last night when I was

called?" said the doctor.

"I don't know, sir. I 'spose I was asleep," replied Sam.

But the doctor was not to be so easily satisfied, after having been put

to so much trouble in hunting up another suit without the aid of Sam.

After breakfast, Sam was taken into the barn, tied up, and severely

flogged with the cat, which brought from him the truth concerning his

absence the previous night. This forever put an end to his fine

appearance at the negro parties. Had not the doctor been one of the

most indulgent of masters, he would not have escaped with merely a

severe whipping.

As a matter of course, Sam had to relate to his companions that evening

in Mr. Wilson's kitchen all his adventures as a physician while with

his old master.

CHAPTER IX

THE MAN OF HONOR.

Augustine Cardinay, the purchaser of Marion, was from the Green

Mountains of Vermont, and his feelings were opposed to the holding of

slaves; but his young wife persuaded him in into the idea that it was

no worse to own a slave than to hire one and pay the money to another.

Hence it was that he had been induced to purchase Marion.

Adolphus Morton, a young physician from the same State, and who had

just commenced the practice of his profession in New Orleans, was

boarding with Cardinay when Marion was brought home. The young

physician had been in New Orleans but a very few weeks, and had seen

but little of slavery. In his own mountain-home, he had been taught

that the slaves of the Southern States were negroes, and if not from

the coast of Africa, the descendants of those who had been imported. He

was unprepared to behold with composure a beautiful white girl of

sixteen in the degraded position of a chattel slave.

The blood chilled in his young heart as he heard Cardinay tell how, by

bantering with the trader, he had bought her two hundred dollars less

than he first asked. His very looks showed that she had the deepest

sympathies of his heart.

Marion had been brought up by her mother to look after the domestic

concerns of her cottage in Virginia, and well knew how to perform the

duties imposed upon her. Mrs. Cardinay was much pleased with her new

servant, and often mentioned her good qualities in the presence of Mr.

Morton.

After eight months acquaintance with Marion, Morton's sympathies

ripened into love, which was most cordially reciprocated by the

friendless and injured child of sorrow. There was but one course which

the young man could honorably pursue, and that was to purchase Marion

and make her his lawful wife; and this he did immediately, for he found

Mr. and Mrs. Cardinay willing to second his liberal intentions.

The young man, after purchasing Marion from Cardinay, and marrying her,

took lodgings in another part of the city. A private teacher was called

in, and the young wife was taught some of those accomplishments so

necessary for one taking a high position in good society.

Dr. Morton soon obtained a large and influential practice in his

profession, and with it increased in wealth; but with all his wealth he

never owned a slave. Probably the fact that he had raised his wife from

that condition kept the hydra-headed system continually before him. To

the credit of Marion be it said, she used every means to obtain the

freedom of her mother, who had been sold to Parson Wilson, at Natchez.

Her efforts, however, had come too late; for Agnes had died of a fever

before the arrival of Dr. Morton's agent.

Marion found in Adolphus Morton a kind and affectionate husband; and

his wish to purchase her mother, although unsuccessful, had doubly

endeared him to her. Ere a year had elapsed from the time of their

marriage, Mrs. Morton presented her husband with a lovely daughter, who

seemed to knit their hearts still closer together. This child they

named Jane; and before the expiration of the second year, they were

blessed with another daughter, whom they named Adrika.

These children grew up to the ages of ten and eleven, and were then

sent to the North to finish their education, and receive that

refinement which young ladies cannot obtain in the Slave States.

CHAPTER X

THE QUADROON'S HOME

A few miles out of Richmond is a pleasant place, with here and there a

beautiful cottage surrounded by trees so as scarcely to be seen. Among

these was one far retired from the public roads, and almost hidden

among the trees. This was the spot that Henry Linwood had selected for

Isabella, the eldest daughter of Agnes. The young man hired the house,

furnished it, and placed his mistress there, and for many months no one

in his father's family knew where he spent his leisure hours.

When Henry was not with her, Isabella employed herself in looking after

her little garden and the flowers that grew in front of her cottage.

The passion-flower peony, dahlia, laburnum, and other plant, so

abundant in warm climates, under the tasteful hand of Isabella,

lavished their beauty upon this retired spot, and miniature paradise.

Although Isabella had been assured by Henry that she should be free and

that he would always consider her as his wife, she nevertheless felt

that she ought to be married and acknowledged by him. But this was an

impossibility under the State laws, even had the young man been

disposed to do what was right in the matter. Related as he was,

however, to one of the first families in Virginia, he would not have

dared to marry a woman of so low an origin, even had the laws been

favorable.

Here, in this secluded grove, unvisited by any other except her lover,

Isabella lived for years. She had become the mother of a lovely

daughter, which its father named Clotelle. The complexion of the child

was still fairer than that of its mother. Indeed, she was not darker

than other white children, and as she grew older she more and more

resembled her father.

As time passed away, Henry became negligent of Isabella and his child,

so much so, that days and even weeks passed without their seeing him,

or knowing where he was. Becoming more acquainted with the world, and

moving continually in the society of young women of his own station,

the young man felt that Isabella was a burden to him, and having as

some would say, "outgrown his love," he longed to free himself of the

responsibility; yet every time he saw the child, he felt that he owed

it his fatherly care.

Henry had now entered into political life, and been elected to a seat

in the legislature of his native State; and in his intercourse with his

friends had become acquainted with Gertrude Miller, the daughter of a

wealthy gentleman living near Richmond. Both Henry and Gertrude were

very good-looking, and a mutual attachment sprang up between them.

Instead of finding fault with the unfrequent visits of Henry, Isabella

always met him with a smile, and tried to make both him and herself

believe that business was the cause of his negligence. When he was with

her, she devoted every moment of her time to him, and never failed to

speak of the growth and increasing intelligence of Clotelle.

The child had grown so large as to be able to follow its father on his

departure out to the road. But the impression made on Henry's feelings

by the devoted woman and her child was momentary. His heart had grown

hard, and his acts were guided by no fixed principle. Henry and

Gertrude had been married nearly two years before Isabella knew

anything of the event, and it was merely by accident that she became

acquainted with the facts.

One beautiful afternoon, when Isabella and Clotelle were picking wild

strawberries some two miles from their home, and near the road-side,

they observed a one-horse chaise driving past. The mother turned her

face from the carriage not wishing to be seen by strangers, little

dreaming that the chaise contained Henry and his wife. The child,

however, watched the chaise, and startled her mother by screaming out

at the top of her voice, "Papa! papa!" and clapped her little hands for

joy. The mother turned in haste to look at the strangers, and her eyes

encountered those of Henry's pale and dejected countenance. Gertrude's

eyes were on the child. The swiftness with which Henry drove by could

not hide from his wife the striking resemblance of the child to

himself. The young wife had heard the child exclaim "Papa! papa!" and

she immediately saw by the quivering of his lips and the agitation

depicted in his countenance, that all was not right.

"Who is that woman? and why did that child call you papa?" she

inquired, with a trembling voice.

Henry was silent; he knew not what to say, and without another word

passing between them, they drove home.

On reaching her room, Gertrude buried her face in her handkerchief and

wept. She loved Henry, and when she had heard from the lips of her

companions how their husbands had proved false, she felt that he was an

exception, and fervently thanked God that she had been so blessed.

When Gertrude retired to her bed that night, the sad scene of the day

followed her. The beauty of Isabella, with her flowing curls, and the

look of the child, so much resembling the man whom she so dearly loved,

could not be forgotten; and little Clotelle's exclamation of "Papa!

Papa" rang in her ears during the whole night.

The return of Henry at twelve o'clock did not increase her happiness.

Feeling his guilt, he had absented himself from the house since his

return from the ride.

CHAPTER XI

TO-DAY A MISTRESS, TO-MORROW A SLAVE

The night was dark, the rain, descended in torrents from the black and

overhanging clouds, and the thunder, accompanied with vivid flashes of

lightning, resounded fearfully, as Henry Linwood stepped from his

chaise and entered Isabella's cottage.

More than a fortnight had elapsed since the accidental meeting, and

Isabella was in doubt as to who the lady was that Henry was with in the

carriage. Little, however, did she think that it was his wife. With a

smile, Isabella met the young man as he entered her little dwelling.

Clotelle had already gone to bed, but her father's voice roused her

from her sleep, and she was soon sitting on his knee.

The pale and agitated countenance of Henry betrayed his uneasiness, but

Isabella's mild and laughing allusion to the incident of their meeting

him on the day of his pleasure-drive, and her saying, "I presume, dear

Henry, that the lady was one of your relatives," led him to believe

that she was still in ignorance of his marriage. She was, in fact,

ignorant who the lady was who accompanied the man she loved on that

eventful day. He, aware of this, now acted more like himself, and

passed the thing off as a joke. At heart, however, Isabella felt

uneasy, and this uneasiness would at times show itself to the young

man. At last, and with a great effort, she said,—

"Now, dear Henry, if I am in the way of your future happiness, say so,

and I will release you from any promises that you have made me. I know

there is no law by which I can hold you, and if there was, I would not

resort to it. You are as dear to me as ever, and my thoughts shall

always be devoted to you. It would be a great sacrifice for me to give

you up to another, but if it be your desire, as great as the sacrifice

is, I will make it. Send me and your child into a Free State if we are

in your way."

Again and again Linwood assured her that no woman possessed his love

but her. Oh, what falsehood and deceit man can put on when dealing with

woman's love!

The unabated storm kept Henry from returning home until after the clock

had struck two, and as he drew near his residence he saw his wife

standing at the window. Giving his horse in charge of the servant who

was waiting, he entered the house, and found his wife in tears.

Although he had never satisfied Gertrude as to who the quadroon woman

and child were, he had kept her comparatively easy by his close

attention to her, and by telling her that she was mistaken in regard to

the child's calling him "papa." His absence that night, however,

without any apparent cause, had again aroused the jealousy of Gertrude;

but Henry told her that he had been caught in the rain while out, which

prevented his sooner returning, and she, anxious to believe him,

received the story as satisfactory.

Somewhat heated with brandy, and wearied with much loss of sleep,

Linwood fell into a sound slumber as soon as he retired. Not so with

Gertrude. That faithfulness which has ever distinguished her sex, and

the anxiety with which she watched all his movements, kept the wife

awake while the husband slept. His sleep, though apparently sound, was

nevertheless uneasy. Again and again she heard him pronounce the name

of Isabella, and more than once she heard him say, "I am not married; I

will never marry while you live." Then he would speak the name of

Clotelle and say, "My dear child, how I love you!"

After a sleepless night, Gertrude arose from her couch, resolved that

she would reveal the whole matter to her mother. Mrs. Miller was a

woman of little or no feeling, proud, peevish, and passionate, thus

making everybody miserable that came near her; and when she disliked

any one, her hatred knew no bounds. This Gertrude knew; and had she not

considered it her duty, she would have kept the secret locked in her

own heart.

During the day, Mrs. Linwood visited her mother and told her all that

had happened. The mother scolded the daughter for not having informed

her sooner, and immediately determined to find out who the woman and

child were that Gertrude had met on the day of her ride. Three days

were spent by Mrs. Miller in this endeavor, but without success.

Four weeks had elapsed, and the storm of the old lady's temper had

somewhat subsided, when, one evening, as she was approaching her

daughter's residence, she saw Henry walking, in the direction of where

the quadroon was supposed to reside. Feeling satisfied that the young

man had not seen her, the old women at once resolved to follow him.

Linwood's boots squeaked so loudly that Mrs. Miller had no difficulty

in following him without being herself observed.

After a walk of about two miles, the young man turned into a narrow and

unfrequented road, and soon entered the cottage occupied by Isabella.

It was a fine starlight night, and the moon was just rising when they

got to their journey's end. As usual, Isabella met Henry with a smile,

and expressed her fears regarding his health.

Hours passed, and still old Mrs. Miller remained near the house,

determined to know who lived there. When she undertook to ferret out

anything, she bent her whole energies to it. As Michael Angelo, who

subjected all things to his pursuit and the idea he had formed of it,

painted the crucifixion by the side of a writhing slave and would have

broken up the true cross for pencils, so Mrs. Miller would have entered

the sepulchre, if she could have done it, in search of an object she

wished to find.

The full moon had risen, and was pouring its beams upon surrounding

objects as Henry stepped from Isabella's door, and looking at his

watch, said,—

"I must go, dear; it is now half-past ten."

Had little Clotelle been awake, she too would have been at the door. As

Henry walked to the gate, Isabella followed with her left hand locked

in his. Again he looked at his watch, and said, "I must go."

"It is more than a year since you staid all night," murmured Isabella,

as he folded her convulsively in his arms, and pressed upon her

beautiful lips a parting kiss.

He was nearly out of sight when, with bitter sobs, the quadroon

retraced her steps to the door of the cottage. Clotelle had in the mean

time awoke, and now inquired of her mother how long her father had been

gone. At that instant, a knock was heard at the door, and supposing

that it was Henry returning for something he had forgotten, as he

frequently did, Isabella flew to let him in. To her amazement, however,

a strange woman stood in the door.

"Who are you that comes here at this late hour?" demanded the

half-frightened Isabella.

Without making any reply, Mrs. Miller pushed the quadroon aside, and

entered the house.

"What do you want here?" again demanded Isabella.

"I am in search of you," thundered the maddened Mrs. Miller; but

thinking that her object would be better served by seeming to be kind,

she assumed a different tone of voice, and began talking in a pleasing

manner.

In this way, she succeeded in finding out the connection existing

between Linwood and Isabella, and after getting all she could out of

the unsuspecting woman, she informed her that the man she so fondly

loved had been married for more than two years. Seized with dizziness,

the poor, heart-broken woman fainted and fell upon the floor. How long

she remained there she could not tell; but when she returned to

consciousness, the strange woman was gone, and her child was standing

by her side. When she was so far recovered as to regain her feet,

Isabella went to the door, and even into the yard, to see if the old

woman was not somewhere about.

As she stood there, the full moon cast its bright rays over her whole

person, giving her an angelic appearance and imparting to her flowing

hair a still more golden hue. Suddenly another change came over her

features, and her full red lips trembled as with suppressed emotion.

The muscles around her faultless mouth became convulsed, she gasped for

breath, and exclaiming, "Is it possible that man can be so false!"

again fainted.

Clotelle stood and bathed her mother's temples with cold water until

she once more revived.

Although the laws of Virginia forbid the education of slaves, Agnes had

nevertheless employed an old free negro to teach her two daughters to

read and write. After being separated from her mother and sister,

Isabella turned her attention to the subject of Christianity, and

received that consolation from the Bible which is never denied to the

children of God. This was now her last hope, for her heart was torn

with grief and filled with all the bitterness of disappointment.

The night passed away, but without sleep to poor Isabella. At the dawn

of day, she tried to make herself believe that the whole of the past

night was a dream, and determined to be satisfied with the explanation

which Henry should give on his next visit.

CHAPTER XII

THE MOTHER-IN-LAW.

When Henry returned home, he found his wife seated at the window,

awaiting his approach. Secret grief was gnawing at her heart. Her sad,

pale cheeks and swollen eyes showed too well that agony, far deeper

than her speech portrayed, filled her heart. A dull and death-like

silence prevailed on his entrance. His pale face and brow, dishevelled

hair, and the feeling that he manifested on finding Gertrude still up,

told Henry in plainer words than she could have used that his wife, was

aware that her love had never been held sacred by him. The

window-blinds were still unclosed, and the full-orbed moon shed her

soft refulgence over the unrivalled scene, and gave it a silvery lustre

which sweetly harmonized with the silence of the night. The clock's

iron tongue, in a neighboring belfry, proclaimed the hour of twelve, as

the truant and unfaithful husband seated himself by the side of his

devoted and loving wife, and inquired if she was not well.

"I am, dear Henry," replied Gertrude; "but I fear you are not. If well

in body, I fear you are not at peace in mind."

"Why?" inquired he.

"Because," she replied, "you are so pale and have such a wild look in

your eyes."

Again he protested his innocence, and vowed she was the only woman who

had any claim upon his heart. To behold one thus playing upon the

feelings of two lovely women is enough to make us feel that evil must

at last bring its own punishment.

Henry and Gertrude had scarcely risen from the breakfast-table next

morning ere old Mrs. Miller made her appearance. She immediately took

her daughter aside, and informed her of her previous night's

experience, telling her how she had followed Henry to Isabella's

cottage, detailing the interview with the quadroon, and her late return

home alone. The old woman urged her daughter to demand that the

quadroon and her child be at once sold to the negro speculators and

taken out of the State, or that Gertrude herself should separate from

Henry.

"Assert your rights, my dear. Let no one share a heart that justly

belongs to you," said Mrs. Miller, with her eyes flashing fire. "Don't

sleep this night, my child, until that wench has been removed from that

cottage; and as for the child, hand that over to me,—I saw at once

that it was Henry's."

During these remarks, the old lady was walking up and down the room