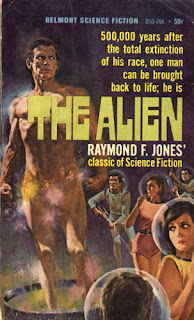

THE ALIEN

A Gripping Novel of Discovery and Conquest

in Interstellar Space

by Raymond F. Jones

A Complete ORIGINAL Book, UNABRIDGED

WORLD EDITIONS, Inc.

105 WEST 40th STREET

NEW YORK 18, NEW YORK

Copyright 1951

by

WORLD EDITIONS, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

THE GUINN CO., Inc.

New York 14, N.Y.

[Transcriber's Note: Extensive research did not uncover any

evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Just speculate for a moment on the enormous challenge to archeology

when interplanetary flight is possible ... and relics are found of a

race extinct for half a million years! A race, incidentally, that was

scientifically so far in advance of ours that they held the secret of

the restoration of life!

One member of that race can be brought back after 500,000 years of

death....

That's the story told by this ORIGINAL book-length novel, which has

never before been published! You can expect a muscle-tightening,

sweat-producing, mind-prodding adventure in the future when you read

it!

Contents

Out beyond the orbit of Mars the Lavoisier wallowed cautiously

through the asteroid fields. Aboard the laboratory ship few of the

members of the permanent Smithson Asteroidal Expedition were aware

that they were in motion. Living in the field one or two years at

a time, there was little that they were conscious of except the

half-million-year-old culture whose scattered fragments surrounded them

on every side.

The only contact with Earth at the moment was the radio link by which

Dr. Delmar Underwood was calling Dr. Illia Morov at Terrestrial Medical

Central.

Illia's blonde, precisely coiffured hair was only faintly golden

against, the stark white of her surgeons' gown, which she still wore

when she answered. Her eyes widened with an expression of pleasure as

her face came into focus on the screen and she recognized Underwood.

"Del! I thought you'd gone to sleep with the mummies out there. It's

been over a month since you called. What's new?"

"Not much. Terry found some new evidence of Stroid III. Phyfe has a

new scrap of metal with inscriptions, and they've found something that

almost looks as if it might have been an electron tube five hundred

thousand years ago. I'm working on that. Otherwise all is peaceful and

it's wonderful!"

"Still the confirmed hermit?" Illia's eyes lost some of their banter,

but none of their tenderness.

"There's more peace and contentment out here than I'd ever dreamed of

finding. I want you to come out here, Illia. Come out for a month. If

you don't want to stay and marry me, then you can go back and I won't

say another word."

She shook her head in firm decision. "Earth needs its scientists

desperately. Too many have run away already. They say the Venusian

colonies are booming, but I told you a year ago that simply running

away wouldn't work. I thought by now you would have found it out for

yourself."

"And I told you a year ago," Underwood said flatly, "that the only

possible choice of a sane man is escape."

"You can't escape your own culture, Del. Why, the expedition that

provided the opportunity for you to become a hermit is dependent on

Earth. If Congress should cut the Institute's funds, you'd be dropped

right back where you were. You can't get away."

"There are always the Venusian colonies."

"You know it's impossible to exist there independent of Earth."

"I'm not talking about the science and technology. I'm talking about

the social disintegration. Certainly a scientist doesn't need to take

that with him when he's attempting to escape it."

"The culture is not to blame," said Illia earnestly, "and neither is

humanity. You don't ridicule a child for his clumsiness when he is

learning to walk."

"I hope the human race is past its childhood!"

"Relatively speaking, it isn't. Dreyer says we're only now emerging

from the cave man stage, and that could properly be called mankind's

infancy, I suppose. Dreyer calls it the 'head man' stage."

"I thought he was a semanticist."

"You'd know if you'd ever talked with him. He'll tear off every other

word you utter and throw it back at you. His 'head man' designation

is correct, all right. According to him, human beings in this stage

need some leader or 'head man' stronger than themselves for guidance,

assumption of responsibility, and blame, in case of failure of the

group. These functions have never in the past been developed in the

individual so that he could stand alone in control of his own ego. But

it's coming—that's the whole import of Dreyer's work."

"And all this confusion and instability are supposed to have something

to do with that?"

"It's been growing for decades. We've seen it reach a peak in our own

lifetimes. The old fetishes have failed, the head men have been found

to be hollow gods, and men's faith has turned to derision. Presidents,

dictators, governors, and priests—they've all fallen from their high

places and the masses of humanity will no longer believe in any of

them."

"And that is development of the race?"

"Yes, because out of it will come a people who have found in themselves

the strength they used to find in the 'head men.' There will come a

race in which the individual can accept the responsibility which he

has always passed on to the 'head man,' the 'head man' is no longer

necessary."

"And so—the ultimate anarchy."

"The 'head man' concept has, but first he has to find out that

has nothing to do with government. With human beings capable of

independent, constructive behavior, actual democracy will be possible

for the first time in the world's history."

"If all this is to come about anyway, according to Dreyer, why not try

to escape the insanity of the transition period?"

Illia Morov's eyes grew narrow in puzzlement as she looked at Underwood

with utter incomprehension. "Doesn't it matter at all that the race is

in one of the greatest crises of all history? Doesn't it matter that

you have a skill that is of immense value in these times? It's peculiar

that it is those of you in the physical sciences who are fleeing in

the greatest numbers. The Venusian colonies must have a wonderful time

with physicists trampling each other to get away from it all—and Earth

almost barren of them. Do the physical sciences destroy every sense of

social obligation?"

"You forget that I don't quite accept Dreyer's theories. To me this is

nothing but a rotting structure that is finally collapsing from its own

inner decay. I can't see anything positive evolving out of it."

"I suppose so. Well, it was nice of you to call, Del. I'm always glad

to hear you. Don't wait so long next time."

"Illia—"

But she had cut the connection and the screen slowly faded into gray,

leaving Underwood's argument unfinished. Irritably, he flipped the

switch to the public news channels.

Where was he wrong? The past year, since he had joined the expedition

as Chief Physicist, was like paradise compared with living in the

unstable, irresponsible society existing on Earth. He knew it was a

purely neurotic reaction, this desire to escape. But application of

that label solved nothing, explained nothing—and carried no stigma.

The neurotic reaction was the norm in a world so confused.

He turned as the news blared abruptly with its perpetual urgency that

made him wonder how the commentators endured the endless flow of crises.

The President had been impeached again—the third one in six months.

There were no candidates for his office.

A church had been burned by its congregation.

Two mayors had been assassinated within hours of each other.

It was the same news he had heard six months ago. It would be the same

again tomorrow and next month. The story of a planet repudiating all

leadership. A lawlessness that was worse than anarchy, because there

was still government—a government that could be driven and whipped by

the insecurities of the populace that elected it.

Dreyer called it a futile search for a 'head man' by a people who would

no longer trust any of their own kind to be 'head man.' And Underwood

dared not trust that glib explanation.

Many others besides Underwood found they could no longer endure the

instability of their own culture. Among these were many of the world's

leading scientists. Most of them went to the jungle lands of Venus. The

scientific limitations of such a frontier existence had kept Underwood

from joining the Venusian colonies, but he'd been very close to going

just before he got the offer of Chief Physicist with the Smithson

Institute expedition in the asteroid fields. He wondered now what he'd

have done if the offer hadn't come.

The interphone annunciator buzzed. Underwood turned off the news as

the bored communications operator in the control room announced, "Doc

Underwood. Call for Doc Underwood."

Underwood cut in. "Speaking," he said irritably.

The voice of Terry Bernard burst into the room. "Hey, Del! Are you

going to get rid of that hangover and answer your phone or should we

embalm the remains and ship 'em back?"

"Terry! You fool, what do you want? Why didn't you say it was you? I

thought maybe it was that elephant-foot Maynes, with chunks of mica

that he thought were prayer sticks."

"The Stroids didn't use prayer sticks."

"All right, skip it. What's new?"

"Plenty. Can you come over for a while? I think we've really got

something here."

"It'd better be good. We're taking the ship to Phyfe. Where are you?"

"Asteroid C-428. It's about 2,000 miles from you. And bring all the

hard-rock mining tools you've got. We can't get into this thing."

"Is that all you want? Use your double coated drills."

"We wore five of them out. No scratches on the thing, even."

"Well, use the Atom Stream, then. It probably won't hurt the artifact."

"I'll say it won't. It won't even warm the thing up. Any other ideas?"

Underwood's mind, which had been half occupied with mulling over his

personal problems while he talked with Terry, swung startledly to what

the archeologist was saying. "You mean that you've found a material

the Atom Stream won't touch? That's impossible! The equations of the

Stream prove—"

"I know. Now will you come over?"

"Why didn't you say so in the first place? I'll bring the whole ship."

Underwood cut off and switched to the Captain's line. "Captain Dawson?

Underwood. Will you please take the ship to the vicinity of Asteroid

C-428 as quickly as possible?"

"I thought Doctor Phyfe—"

"I'll answer for it. Please move the vessel."

Captain Dawson acceded. His instructions were to place the ship at

Underwood's disposal.

Soundlessly and invisibly, the distortion fields leaped into

space about the massive laboratory ship and the Lavoisier moved

effortlessly through the void. Its perfect inertia controls left no

evidence of its motion apparent to the occupants with the exception of

the navigators and pilots. The hundreds of delicate pieces of equipment

in Underwood's laboratories remained as steadfast as if anchored to

tons of steel and concrete deep beneath the surface of Earth.

Twenty minutes later they hove in sight of the small, black asteroid

that glistened in the faint light of the faraway Sun. The spacesuited

figures of Terry Bernard and his assistant, Batch Fagin, clung to the

surface, moving about like flies on a blackened, frozen apple.

Underwood was already in the scooter lock, astride the little

spacescooter which they used for transportation between ships of the

expedition and between asteroids.

The pilot jockeyed the Lavoisier as near as safely desirable, then

signaled Underwood. The physicist pressed the control that opened

the lock in the side of the vessel. The scooter shot out into space,

bearing him astride it.

"Ride 'em, cowboy!" Terry Bernard yelled into the intercom. He gave a

wild cowboy yell that pierced Underwood's ears. "Watch out that thing

doesn't turn turtle with you."

Underwood grinned to himself. He said, "Your attitude convinces me of a

long held theory that archeology is no science. Anyway, if your story

of a material impervious to the Atom Stream is wrong, you'd better get

a good alibi. Phyfe had some work he wanted to do aboard today."

"Come and see for yourself. This is it."

As the scooter approached closer to the asteroid, Underwood could

glimpse the strangeness of the thing. It looked as if it had been

coated with the usual asteroid material of nickel iron debris, but

Terry had cleared this away from more than half the surface.

The exposed half was a shining thing of ebony, whose planes and angles

were machined with mathematical exactness. It looked as if there were

at least a thousand individual facets on the one hemisphere alone.

At the sight of it, Underwood could almost understand the thrill of

discovery that impelled these archeologists to delve in the mysteries

of space for lost kingdoms and races. This object which Terry had

discovered was a magnificent artifact. He wondered how long it had

circled the Sun since the intelligence that formed it had died. He

wished now that Terry had not used the Atom Stream, for that had

probably destroyed the validity of the radium-lead relationship in the

coating of debris that might otherwise indicate something of the age of

the thing.

Terry sensed something of Underwood's awe in his silence as he

approached. "What do you think of it, Del?"

"It's—beautiful," said Underwood. "Have you any clue to what it is?"

"Not a thing. No marks of any kind on it."

The scooter slowed as Del Underwood guided it near the surface of the

asteroid. It touched gently and he unstrapped himself and stepped off.

"Phyfe will forgive all your sins for this," he said. "Before you show

me the Atom Stream is ineffective, let's break off a couple of tons of

the coating and put it in the ship. We may be able to date the thing

yet. Almost all these asteroids have a small amount of radioactivity

somewhere in them. We can chip some from the opposite side where the

Atom Stream would affect it least."

"Good idea," Terry agreed. "I should have thought of that, but when

I first found the single outcropping of machined metal, I figured it

was very small. After I found the Atom Stream wouldn't touch it, I was

overanxious to undercover it. I didn't realize I'd have to burn away

the whole surface of the asteroid."

"We may as well finish the job and get it completely uncovered. I'll

have some of my men from the ship come on over."

It took the better part of an hour to chip and drill away samples to be

used in a dating attempt. Then the intense fire of the Atom Stream was

turned upon the remainder of the asteroid to clear it.

"We'd better be on the lookout for a soft spot." Terry suggested. "It's

possible this thing isn't homogeneous, and Papa Phyfe would be very

mad if we burned it up after making such a find."

From behind his heavy shield which protected him from the stray

radiation formed by the Atom Stream, Delmar Underwood watched the

biting fire cut between the gemlike artifact and the metallic alloys

that coated it. The alloys cracked and fell away in large chunks,

propelled by the explosions of matter as the intense heat vaporized the

metal almost instantly.

The spell of the ancient and the unknown fell upon him and swept him up

in the old mysteries and the unknown tongues. Trained in the precise

methods of the physical sciences, he had long fought against the

fascination of the immense puzzles which the archeologists were trying

to solve, but no man could long escape. In the quiet, starlit blackness

there rang the ancient memories of a planet vibrant with life, a

planet of strange tongues and unknown songs—a planet that had died

so violently that space was yet strewn with its remains—so violently

that somewhere the echo of its death explosion must yet ring in the far

vaults of space.

Underwood had always thought of archeologists as befogged antiquarians

poking among ancient graves and rubbish heaps, but now he knew them

for what they were—poets in search of mysteries. The Bible-quoting of

Phyfe and the swearing of red-headed Terry Bernard were merely thin

disguises for their poetic romanticism.

Underwood watched the white fire of the Atom Stream through the lead

glass of the eye-protecting lenses. "I talked to Illia today," he said.

"She says I've run away."

"Haven't you?" Terry asked.

"I wouldn't call it that."

"It doesn't make much difference what you call it. I once lived in an

apartment underneath a French horn player who practised eight hours a

day. I ran away. If the whole mess back on Earth is like a bunch of

horn blowers tootling above your apartment, I say move, and why make

any fuss about it? I'd probably join the boys on Venus myself if my job

didn't keep me out here. Of course it's different with you. There's

Illia to be convinced—along with your own conscience."

"She quotes Dreyer. He's one of your ideals, isn't he?"

"No better semanticist ever lived," Terry said flatly. "He takes the

long view, which is that everything will come out in the wash. I agree

with him, so why worry—knowing that the variants will iron themselves

out, and nothing I can possibly do will be noticed or missed? Hence,

I seldom worry about my obligations to mankind, as long as I stay

reasonably law-abiding. Do likewise, Brother Del, and you'll live

longer, or at least more happily."

Underwood grinned in the blinding glare of the Atom Stream. He wished

life were as simple as Terry would have him believe. Maybe it would be,

he thought—if it weren't for Illia.

As he moved his shield slowly forward behind the crumbling debris,

Underwood's mind returned to the question of who created the structure

beneath their feet, and to what alien purpose. Its black, impenetrable

surfaces spoke of excellent mechanical skill, and a high science that

could create a material refractory to the Atom Stream. Who, a half

million years ago, could have created it?

The ancient pseudo-scientific Bode's Law had indicated a missing planet

which could easily have fitted into the Solar System in the vicinity

of the asteroid belt. But Bode's Law had never been accepted by

astronomers—until interstellar archeology discovered the artifacts of

a civilization on many of the asteroids.

The monumental task of exploration had been undertaken more than a

generation ago by the Smithson Institute. Though always handicapped by

shortage of funds, they had managed to keep at least one ship in the

field as a permanent expedition.

Dr. Phyfe, leader of the present group, was probably the greatest

student of asteroidal archeology in the System. The younger

archeologists labeled him benevolently Papa Phyfe, in spite of the

irascible temper which came, perhaps, from constantly switching his

mind from half a million years ago to the present.

In their use of semantic correlations, Underwood was discovering, the

archeologists were far ahead of the physical scientists, for they had

an immensely greater task in deducing the mental concepts of alien

races from a few scraps of machinery and art.

Of all the archeologists he had met, Underwood had taken the greatest

liking to Terry Bernard. An extremely competent semanticist and

archeologist, Terry nevertheless did not take himself too seriously. He

did not even mind Underwood's constant assertion that archeology was

no science. He maintained that it was fun, and that was all that was

necessary.

At last, the two groups approached each other from opposite sides of

the asteroid and joined forces in shearing off the last of the debris.

As they shut off the fearful Atom Streams, the scientists turned to

look back at the thing they had cleared.

Terry said quietly, "See why I'm an archeologist?"

"I think I do—almost," Underwood answered.

The gemlike structure beneath their feet glistened like polished ebony.

It caught the distant stars in its thousand facets and cast them until

it gleamed as if with infinite lights of its own.

The workmen, too, were caught in its spell, for they stood silently

contemplating the mystery of a people who had created such beauty.

The spell was broken at last by a movement across the heavens.

Underwood glanced up. "Papa Phyfe's coming on the warpath. I'll bet

he's ready to trim my ears for taking the lab ship without his consent."

"You're boss of the lab ship, aren't you?" said Terry.

"It's a rather flexible arrangement—in Phyfe's mind, at least. I'm

boss until he decides he wants to do something."

The headquarters ship slowed to a halt and the lock opened, emitting

the fiery burst of a motor scooter which Doc Phyfe rode with angry

abandon.

"You, Underwood!" His voice came harshly through the phones. "I demand

an explanation of—"

That was as far as he got, for he glimpsed the thing upon which the

men were standing, and from his vantage point it looked all the more

like a black jewel in the sky. He became instantly once more the eager

archeologist instead of expedition administrator, a role he filled with

irritation.

"What have you got there?" he whispered.

Terry answered. "We don't know. I asked Dr. Underwood's assistance in

uncovering the artifact. If it caused you any difficulty, I'm sorry;

it's my fault."

"Pah!" said Phyfe. "A thing like this is of utmost importance. You

should have notified me immediately."

Terry and Underwood grinned at each other. Phyfe reprimanded every

archeologist on the expedition for not notifying him immediately

whenever anything from the smallest machined fragment of metal to the

greatest stone monuments were found. If they had obeyed, he would have

done nothing but travel from asteroid to asteroid over hundreds of

thousands of miles of space.

"You were busy with your own work," said Terry.

But Phyfe had landed, and as he dismounted from the scooter, he stood

in awe. Terry, standing close to him, thought he saw tears in the old

man's eyes through the helmet of the spaceship.

"It's beautiful!" murmured Phyfe in worshipping awe. "Wonderful. The

most magnificent find in a century of asteroidal archeology. We must

make arrangements for its transfer to Earth at once."

"If I may make a suggestion," said Terry, "you recall that some of the

artifacts have not survived so well. Decay in many instances has set

in—"

"Are you trying to tell me that this thing can decay?" Phyfe's little

gray Van Dyke trembled violently.

"I'm thinking of the thermal transfer. Doctor Underwood is better able

to discuss that, but I should think that a mass of this kind, which is

at absolute zero, might undergo unusual stresses in coming to Earth

normal temperatures. True, we used the Atom Stream on it, but that heat

did not penetrate enough to set up great internal stresses."

Phyfe looked hesitant and turned to Underwood. "What is your opinion?"

Underwood didn't get it until he caught Terry's wink behind Phyfe's

back. Once it left space and went into the museum laboratory, Terry

might never get to work on the thing again. That was the perpetual

gripe of the field men.

"I think Doctor Bernard has a good point," said Underwood. "I would

advise leaving the artifact here in space until a thorough examination

has been made. After all, we have every facility aboard the Lavoisier

that is available on Earth."

"Very well," said Phyfe. "You may proceed in charge of the physical

examination of the find, Doctor Underwood. You, Doctor Bernard, will be

in charge of proceedings from an archeological standpoint. Will that

be satisfactory to everyone concerned?"

It was far more than Terry had expected.

"I will be on constant call," said Phyfe. "Let me know immediately of

any developments." Then the uncertain mask of the executive fell away

from the face of the little old scientist and he regarded the find with

humility and awe. "It's beautiful," he murmured again, "beautiful."

Phyfe remained near the site as Underwood and Terry set their crew to

the routine task of weighing, measuring, and photographing the object,

while Underwood considered what else to do.

"You know, this thing has got me stymied, Terry. Since it can't be

touched by an Atom Stream, that means there isn't a single analytical

procedure to which it will respond—that I know of, anyway. Does your

knowledge of the Stroids and their ways of doing things suggest any

identification of it?"

Terry shook his head as he stood by the port of the laboratory ship

watching the crews at work outside. "Not a thing, but that's no

criterion. We know so little about the Stroids that almost everything

we find has a function we never heard of before. And of course

we've found many objects with totally unknown functions. I've been

thinking—what if this should turn out to be merely a natural gem

from the interior of the planet, maybe formed at the time of its

destruction, but at least an entirely natural object rather than an

artifact?"

"It would be the largest crystal formation ever encountered, and

the most perfect. I'd say the chances of its natural formation are

negligible."

"But maybe this is the one in a hundred billion billion or whatever

number chance it may be."

"If so, its value ought to be enough to balance the Terrestrial budget.

I'm still convinced that it must be an artifact, though its material

and use are beyond me. We can start with a radiation analysis. Perhaps

it will respond in some way that will give us a clue."

When the crew had finished the routine check, Underwood directed his

men to set up the various types of radiation equipment contained within

the ship. It was possible to generate radiation through almost the

complete spectrum from single cycle sound waves to hard cosmic rays.

The work was arduous and detailed. Each radiator was slowly driven

through its range, then removed and higher frequency equipment used. At

each fraction of an octave, the object was carefully photographed to

record its response.

After watching the work for two days, Terry wearied of the seemingly

non-productive labor. "I suppose you know what you're doing, Del," he

said. "But is it getting you anywhere at all?"

Underwood shook his head. "Here's the batch of photographs. You'll

probably want them to illustrate your report. The surfaces of the

object are mathematically exact to a thousandth of a millimeter.

Believe me, that's some tolerance on an object of this size. The

surfaces are of number fifteen smoothness, which means they are plane

within a hundred-thousandth of a millimeter. The implications are

obvious. The builders who constructed that were mechanical geniuses."

"Did you get any radioactive dating?"

"Rather doubtfully, but the indications are around half a million

years."

"That checks with what we know about the Stroids."

"It would appear that their culture is about on a par with our own."

"Personally, I think they were ahead of us," said Terry. "And do you

see what that means to us archeologists? It's the first time in the

history of the science that we've had to deal with the remains of a

civilization either equal or superior to our own. The problems are

multiplied a thousand times when you try to take a step up instead of a

step down."

"Any idea of what the Stroids looked like?"

"We haven't found any bodies, skeletons, or even pictures, but we think

they were at least roughly anthropomorphic. They were farther from the

Sun than we, but it was younger then and probably gave them about the

same amount of heat. Their planet was larger and the Stroids appear

to have been somewhat larger as individuals than we, judging from

the artifacts we've discovered. But they seem to have had a suitable

atmosphere of oxygen diluted with appropriate inert gases."

They were interrupted by the sudden appearance of a laboratory

technician who brought in a dry photographic print still warm from the

developing box.

He laid it on the desk before Underwood. "I thought you might be

interested in this."

Underwood and Terry glanced at it. The picture was of the huge,

gemlike artifact, but a number of the facets seemed to be covered with

intricate markings of short, wavy lines.

Underwood stared closer at the thing. "What the devil are those? We

took pictures of every facet previously and there was nothing like

this. Get me an enlargement of these."

"I already have." The assistant laid another photo on the desk, showing

the pattern of markings as if at close range. They were clearly

discernible now.

"What do you make of it?" asked Underwood.

"I'd say it looked like writing," Terry said. "But it's not like any

of the other Stroid characters I've seen—which doesn't mean much, of

course, because there could be thousands that I've never seen. Only how

come these characters are there now, and we never noticed them before?"

"Let's go out and have a look," said Underwood. He grasped the

photograph and noted the numbers of the facets on which the characters

appeared.

In a few moments the two men were speeding toward the surface of their

discovery astride scooters. They jockeyed above the facets shown on the

photographs, and stared in vain.

"Something's the matter," said Terry. "I don't see anything here."

"Let's go all the way around on the scooters. Those guys may have

bungled the job of numbering the photos."

They began a slow circuit, making certain they glimpsed all the facets

from a height of only ten feet.

"It's not here," Underwood agreed at last. "Let's talk to the crew that

took the shots."

They headed towards the equipment platform, floating in free space,

from which Mason, one of the Senior Physicists, was directing

operations. Mason signaled for the radiations to be cut off as the men

approached.

"Find any clues, Chief?" he asked Underwood. "We've done our best to

fry this apple, but nothing happens."

"Something did happen. Did you see it?" Underwood extended the

photograph with the mechanical fingers of the spacesuit. Mason held it

in a light and stared at it. "We didn't see a thing like that. And we

couldn't have missed it." He turned to the members of the crew. "Anyone

see this writing on the thing?"

They looked at the picture and shook their heads.

"What were you shooting on it at the time?"

Mason glanced at his records. "About a hundred and fifty angstroms."

"So there must be something that becomes visible only in a field of

radiation of about that wave length," said Underwood. "Keep going and

see if anything else turns up, or if this proves to be permanent after

exposure to that frequency."

Back in the laboratory, they sat down at the desk and went through

the file of hundreds of photographs that were now pouring out of the

darkroom.

"Not a thing except that one," said Terry. "It looks like a message

intended only for someone who knew what frequency would make it

visible."

Underwood shook his head. "That sounds a little too melodramatic for

me. Yet it is possible that this thing is some kind of repository, and

we've found the key to it. But what a key! It looks as if we've got to

decipher the language of the Stroids in order to use the key."

"The best men in the field have been trying to do that for only about

seventy-five years. If that's what it takes, we may as well quit right

now."

"You said that this was nothing like any other Stroid characters that

you had seen. Maybe this belongs to a different cultural stratum. It

might prove easier to crack. Who's the best man in the field on this

stuff?"

"Dreyer at the semantics lab. He won't touch it any more. He says he's

wasted fifteen years of his life on the Stroid inscriptions."

"I'll bet he will tackle this, if it's as new as you think it is. I've

seen some of those antiquarians before. We'll get Phyfe to transmit

some copies of this to him. Who's the next best man?"

"Probably Phyfe himself."

"It won't be hard to get him started on it, I'll bet."

It wasn't. The old scientist was ecstatic over the discovery of the

inscriptions upon the huge gem. He took copies of the pictures into his

study and spent two full days comparing them with the known records.

"It's an entirely new set of characters," he said after completing the

preliminary examination. "We already have three sets of characters that

seem to be in no way related. This is the fourth."

"You sent copies to Dreyer?"

"Only because you requested it. Dreyer admitted long ago that he was

licked."

During the week of Phyfe's study, the work of radiation analysis had

been completed. It proved completely negative with the single exception

of the 150 A. radiation which rendered visible the characters on the

gem. No secondary effects of any significance whatever had been noted.

The material reflected almost completely nearly every frequency imposed

upon it.

Thus, Underwood found himself again at the end of his resources. It

was impossible to analyze material that refused to react, which was

refractive to every force applied.

Underwood told Terry at the conclusion of a series of chemical tests,

"If you want to keep that thing out here any longer, I'm afraid

you've got to think of some more effective way of examining it than

I have been able to do. From a physical standpoint this artifact is

in about the same position as the language of the Stroids had been

semantically—completely intractable."

"I'm not afraid of its being sent back to the museum now. Papa Phyfe's

got his teeth into it and he won't let go until he cracks the key to

this lingo."

Underwood didn't believe that it would ever be solved, unless by

some lucky chance they came upon a sort of Rosetta Stone which would

bridge the gap between the human mind and that of the alien Stroids.

Even if the Stroids were somewhat anthropomorphic in makeup as the

archeologists believed, there was no indication that their minds would

not be so utterly alien that no bridge would even be possible.

Underwood felt seriously inclined to abandon the problem. While

completely fascinating, it was hardly more soluble than was the problem

of the composition of the stars in the days before the spectroscope

was invented. Neither the archeologists, the semanticists, nor the

physicists yet had the tools to crack the problem of the Stroids. Until

the tools became available, the problem would simply have to go by the

boards. The only exception was the remote possibility of a deliberate

clue left by the Stroids themselves, but Underwood did not believe in

miracles.

His final conviction came when word came back from Dreyer, who said,

"Congratulations, Phyfe," and returned the copies of the Stroid

characters with a short note.

"Well, that does it," said Underwood.

Phyfe was dismayed by Dreyer's reply. "The man's simply trying to

uphold a decaying reputation by claiming the problem can't be solved.

Send it to the museum and let them begin work on it. I'll give it my

entire time. You will help me, if you will, Doctor Bernard."

Terry himself was becoming somewhat dismayed by the magnitude of the

mystery they had uncovered. He knew Phyfe's bulldog tenacity when he

tackled something and he didn't want to be tied to semantics for the

rest of the term of the expedition.

Underwood, however, had become immersed in X-ray work, attempting

to determine the molecular structure of the artifact from a

crystallographic standpoint, to find out if it could be found it might

be possible to disrupt the pattern.

After he had been at it for about a week, Terry came into the lab in a

disgruntled mood at the completion of a work period.

"You look as if Papa gave you a spanking," said Underwood. "Why the

downcast mood?"

"I think I'll resign and go back to the museum. It's useless to work on

this puzzle any longer."

"How do you know?"

"Because it doesn't follow the laws of semantics with respect to

language."

"Maybe the laws need changing."

"You know better than that. Look, you are as familiar with Carnovan's

law as I am. It states that in any language there is bound to be a

certain constant frequency of semantic conceptions. It's like the

old frequency laws that used to be used in cryptographic analysis

except a thousand times more complex. Anyway, we've made thousands of

substitutions into Carnovan's frequency scale and nothing comes out.

Not a thing. No concept of ego, identity, perfection, retrogression, or

intercourse shows up. The only thing that registers in the slightest

degree is the concept of motion, but it doesn't yield a single key

word. It's almost as if it weren't even a language."

"Maybe it isn't."

"What else could it be?"

"Well, maybe this thing we've found is a monument of some kind and

the inscriptions are ritualistic tributes to dead heroes or something.

Maybe there's no trick at all about the radiation business. Maybe

they used that frequency for common illumination and the inscription

was arranged to show up just at night. The trouble with you strict

semanticists is that you don't use any imagination."

"Like to try a hand at a few sessions with Papa Phyfe?"

"No, thanks, but I do think there are other possibilities that you

are overlooking. I make no claim to being anything but a strictly ham

semanticist, but suppose, for example, that the inscriptions are not

language at all in the common sense."

"They must represent transfer of thought in some form."

"True, but look at the varied forms of thought. You are bound down to

the conception of language held as far back as Korzybski. At least to

the conception held by those who didn't fully understand Korzybski. You

haven't considered the concept of music. It's a very real possibility,

but one which would remain meaningless without the instrument. Consider

also—Wait a minute, Terry! We've all been a bunch of thoroughbred

dopes!"

"What is it?"

"Look at the geometrical and mechanical perfection of the artifact.

That implies mathematical knowledge of a high order. The inscriptions

could be mathematical measurements of some kind. That would explain the

breakdown of Carnovan's principles. They don't apply to math."

"But what kind of math would be inscribed on a thing like that?"

"Who knows? We can give it a try."

It was the beginning of their sleeping period, but Terry was fired with

Underwood's sudden enthusiasm. He brought in a complete copy of all the

inscriptions found upon the facets of the black gem. Underwood placed

them on a large table in continuous order as they appeared around the

circumference.

"It's mud to me," said Terry. "I'm the world's worst mathematician."

"Look!" exclaimed Underwood. "Here's the beginning of it." He suddenly

moved some of the sheets so that one previously in the middle formed

the beginning of the sequence. "What does it look like to you?"

"I've seen that until I dream of it. It's one Phyfe tried to make the

most of in his frequency determinations. It looks like nothing more

than some widgets alongside a triangle."

"That's exactly what it is, and no wonder Phyfe found it had a high

frequency. That is nothing more nor less than an explanation of the

Stroid concept of the differential. This widget over here must be the

sign of the derivative corresponding to our dy/dx."

Hastily, Underwood scrawled some symbols on a scratch pad, using

combinations of "x"s and "y"s and the strange, unknown symbols of the

Stroids.

"It checks. They're showing us how to differentiate! Not only that,

we have the key to their numerical system in the exponentials,

because they've given us the differentiation of a whole series of

power expressions here. Now, somewhere we ought to find an integral

expression which we could check back with differentiation. Here it is!"

Terry, left behind now, went to the galley and brewed a steaming pot of

coffee and brought it back. He found Underwood staring unseeingly ahead

of him into the dark, empty corners of the lab.

"What is it?" Terry exclaimed. "What have you found?"

"I'm not sure. Do you know what the end product of all this math is?"

"What?"

"A set of wave equations, but such wave equations as any physicist

would be thought crazy to dream up. Yet, in light of some new

manipulations introduced by the Stroids, they seem feasible."

"What can we do with them?"

"We can build a generator and see what kind of stuff comes out of

it when we operate it according to this math. The Stroids obviously

intended that someone find this and learn to produce the radiation

described. For what purpose we can only guess—but we might find out."

"Do we have enough equipment aboard to build such a generator?"

"I think so. We could cannibalize enough from equipment we already have

on hand. Let's try it."

Terry hesitated. "I'm not quite sure, but—well, this stuff comes about

as near as anything I ever saw to giving me what is commonly known as

the creeps. Somehow these Stroids seem too—too anxious. That sounds

crazy, I know, but there's such alienness here."

"Nuts. Let's build their generator and see what they're trying to tell

us."

Phyfe was exuberant. He not only gave permission to construct the

generator, he demanded that all work aboard the lab ship give priority

to the new project.

The design of the machine was no easy task, for Underwood was a

physicist and not an engineer. However, he had two men, Moody and

Hansen, in his staff who were first rate engineers. On them fell

the chief burden of design after Underwood worked out the rough

specifications.

One of the main laboratories with nearly ten thousand square feet of

floor space was cleared for the project. As the specifications flowed

from Underwood's desk, they passed over to Moody and Hansen, and from

there out to the lab where the mass of equipment was gathered from all

parts of the fleet.

An atomic power supply sufficient to give the large amount of energy

required by the generator was obtained by robbing the headquarters

ship of its auxiliary supply. Converter units were available in the

Lavoisier itself, but the main radiator tubes had to be cannibalized

from the 150 A equipment aboard.

Slowly the mass of improvised equipment grew. It would have been a

difficult task on Earth with all facilities available for such a

project, but with these makeshift arrangements it was a miracle that

the generator continued to develop. A score of times Underwood had to

make compromises that he hoped would not alter the characteristics of

the wave which, two weeks before, he would have declared impossible to

generate.

When the equipment was completed and ready for a trial check, the huge

lab was a mass of hay-wiring into which no one but Moody and Hansen

dared go.

The completion was an anti-climax. The great project that had almost

halted all other field work was finished—and no one knew what to

expect when Hansen threw the switch that fed power from the converters

into the giant tubes.

As a matter of fact, nothing happened. Only the faint whine of the

converters and the swinging needles of meters strung all over the room

showed that the beam was in operation.

On the nose of the Lavoisier was the great, ungainly radiator a

hundred feet in diameter, which was spraying the unknown depths of

space with the newly created power.

Underwood and Terry were outside the ship, behind the huge radiator,

with a mass of equipment designed to observe the effects of the beam.

In space it was totally invisible, creating no detectable field. It

seemed as inactive as a beam of ultraviolet piercing the starlit

darkness.

Underwood picked up the interphone that connected them with the

interior of the ship. "Swing around, please, Captain Dawson. Let the

beam rotate through a one hundred and eighty degree arc."

The Captain ordered the ship around and the great Lavoisier swung

on its own axis—but not in the direction Underwood had had in mind.

He failed to indicate the direction, and Dawson had assumed it didn't

matter.

Ponderously, the great radiator swung about before Underwood could

shout a warning. And the beam came directly in line with the mysterious

gem of the universe which they had found in the heart of the asteroid.

At once, the heavens were filled with intolerable light. Terry and

Underwood flung themselves down upon the hull of the ship and the

physicist screamed into the phones for Dawson to swing the other way.

But his warnings were in vain, for those within the ship were blinded

by the great flare of light that penetrated even the protective ports

of the ship. Irresistibly, the Lavoisier continued to swing, spraying

the great gem with its mysterious radiation.

Then it was past and the beam cut into space once more.

On top of the ship, Underwood and Terry found their sight slowly

returning. They had been saved the full blast of the light from the gem

by the curve of the ship's hull which cut it off.

Underwood stumbled to his feet, followed by Terry. The two men stood

in open-mouthed un-belief at the vision that met their eyes. Where the

gem had drifted in space, there was now a blistered, boiling mass of

amorphous matter that surged and steamed in the void. All semblance to

the glistening, faceted, ebon gem was gone as the repulsive mass heaved

within itself.

"It's destroyed!" Terry exclaimed hoarsely. "The greatest archeological

find of all time and we destroy it before we find out anything about

it—"

"Shut up!" Underwood commanded harshly. He tried to concentrate on the

happenings before him, but he could find no meaning in it. He bemoaned

the fact that he had no camera, and only prayed that someone inside

would have the wit to turn one on.

As the ship continued its slow swing like a senseless animal, the

pulsing of the amorphous mass that had been the jewel slowly ceased.

And out of the gray murkiness of it came a new quality. It began to

regain rigidity—and transparency!

Underwood gasped. At the boundary lines of the facets, heavy ribs

showed the tremendously reinforced structure that formed the skeleton.

And each cell between the ribs was filled with thick substance that

partially revealed the unknown world within.

But more than that, between one set of ribs he glimpsed what he was

sure was an emptiness, a doorway to the interior!

"Come on," he called to Terry. "Look at that opening!"

They leaped astride the scooters clamped to the surface of the lab

ship and sped into space between the two objects. It required only an

instant to confirm his first hasty glimpse.

They navigated the scooters close to the opening and clamped them to

the surface. For a moment, Underwood thought the gem might be some

strange ship from far out of the Universe, for it seemed filled with

mechanism of undescribable characteristics and unknown purposes. It was

so filled that it was impossible to see very far into the interior even

with the help of the powerful lamps on the scooters.

"The beam was the key to get into the thing," said Terry. "It was

intended all along that the beam be turned on it. The beam had to be

connected with the gem in some way."

"And what a way!"

The triangular opening was large enough to admit a man. Underwood and

Terry knelt at the edge of it, peering down, flashing their lights

about the revealed interior. The opening seemed to drop into the center

of a small room that was bare.

"Come into my parlor, said the spider to the fly," quoted Terry. "I

don't see anything down there, do you?"

"No. Why the spider recitation?"

"I don't know. Everything is too pat. I feel as if someone is watching

behind us, practically breathing down our necks and urging us on the

way he wants us to go. And when we get there we aren't going to like

it."

"I suppose that is strictly a scientific hunch which we ignorant

physicists wouldn't understand."

But Terry was serious. The whole aspect of the Stroid device was

unnerving in the way it led along from step to step, as if unseen

powers were guiding them, rather than using their own initiative in

their work.

Underwood gave a final grunt and dropped into the hole, flashing his

light rapidly about. Terry followed immediately. They found themselves

in the center of a circular room twenty feet in diameter. The walls

and the floor seemed to be of the same ebony-black material that had

composed the outer shell of the gem before its transmutation.

The walls were literally covered from the floor to the ten-foot

ceiling with inscriptions that glowed faintly in the darkness when the

flashlights were not turned on them.

"Recognize any of this stuff?" asked Underwood.

"Stroid III," said Terry in awe. "The most beautiful collection

of engravings that have ever been found. We've never obtained a

consecutive piece even a fraction this size before. Dreyer has got to

come now."

"I've got a hunch about this," said Underwood slowly. "I don't know a

thing about the procedures used in deciphering an unknown lingo, but

I'll bet you find that this is an instruction primer to their language,

just as the inscriptions outside gave the key to their math before

detailing the wave equations."

"You might be right!" Terry's eyes glowed with enthusiasm as he looked

about the polished walls with the faintly glowing characters inlaid in

them. "If that's the case, Papa Phyfe and I ought to be able to do the

job without Dreyer."

They returned to the ship for photographic equipment and to report

their finding to Phyfe. It was a little difficult for him to adjust to

the view that something had been gained in the transformation of the

gem. The sight of that boiling, amorphous mass in space had been to him

like helplessly standing on the bank of a stream and watching a loved

one drown.

But with Terry's report on the characters in Stroid III which lined the

walls of the antechamber which they had penetrated, he was ready to

admit that their position had improved.

Underwood was merely a by-stander as they returned to the gem. Two

photographers, Carson and Enright, accompanied them along with Nichols,

assistant semanticist.

Underwood stood by, in the depths of speculation, as the photographers

set up their equipment and Phyfe bent down to examine the characters at

close range.

Terry continued to be dogged by the feeling that they were being led

by the nose into something that would end unpleasantly. He didn't know

why, except that the fact of immense and meticulous preparation was

evidenced on all sides. It was the reason for that preparation which

made him wonder.

Phyfe said to Underwood, "Doctor Bernard tells me your opinion is that

this room is a key to Stroid III. You may be right, but I fail to find

any indication of it at present. What gives you that idea?"

"The whole setup," said Underwood. "First, there was the impenetrable

shell. Nothing like it exists in Solarian culture today. Then there

was the means by which we were able to read the inscriptions on the

outside. Obviously, if heat and fission reactions as well as chemical

reactions could not touch the stuff, the only remaining means of

analysis was radiative. And the only peoples who could discover the

inscriptions were those capable of building a generator of 150 A.

radiations. We have there two highly technical requirements of anyone

attempting to solve the secret of this cache—ability to generate the

proper radiation, and the ability to understand their mathematics and

build a second generator from their wave equations.

"Now that we're in here, there is nothing more we can do until we can

understand their printed language. Obviously, they must teach it to us.

This would be the place."

"You may be right," said Phyfe, "But we archeologists work with facts,

not guesses. We'll know soon enough if it's true."

Underwood felt content to speculate while the others worked. There was

nothing else for him to do. No way out of the anteroom was apparent,

but he was confident that a way to the interior would be found when the

inscriptions were deciphered.

He went out to the surface and walked slowly about, peering into the

transparent depths with his light. What lay within this repository

left by an ancient race that had obviously equaled or surpassed man

in scientific attainments? Would it be some vast store of knowledge

that would come to bless mankind with greater abundance? Or would it,

rather, be a new Pandora's box, which would pour out upon the world new

ills to add to its already staggering burden?

The world had about all it could stand now, Underwood reflected. For a

century, Earth's scientific production had boomed. Her factories had

roared with the throb of incessant production, and the utopia of all

the planners of history was gradually coming to pass. Man's capacities

for production had steadily increased for five hundred years, and

at last the capacities for consumption were rising equally, with

correspondingly less time spent in production and greater time spent in

consumption.

But the utopia wasn't coming off just as the Utopians had dreamed of

it. The ever present curse of enforced leisure was not respecting the

new age any more than it had past ages. Men were literally being driven

crazy with their super-abundance of luxury.

Only a year before, the so-called Howling Craze had swept cities

and nations. It was a wave of hysteria that broke out in epidemic

proportions. Thousands of people within a city would be stricken at

a time by insensate weeping and despair. One member of a household

would be afflicted and quickly it would spread from that man to the

family, and from that family it would race the length and breadth of

the streets, up and down the city, until one vast cry as of a stricken

animal would assault the heavens.

Underwood had seen only one instance of the Howling Craze and he had

fled from it as if pursued. It was impossible to describe its effects

upon the nervous system—a whole city in the throes of hysteria.

Life was cheap, as were the other luxuries of Earth. Murders by the

thousands each month were scarcely noticed, and the possession of

weapons for protection had become a mark of the new age, for no man

knew when his neighbor might turn upon him.

Governments rose and fell swiftly and became little more than

figureheads to carry out the demands of peoples cloyed with the

excesses of life. Most significant of all, however, was the inability

of any leader to hold any following for more than a short time.

Of all the inhabitants of Earth, there were but a few hundred thousand

scientists who were able to keep themselves on even keel, and most of

these were now fleeing.

As he thought of these things, Underwood pondered what the opening of

the repository of a people who sealed up their secrets half a million

years ago would mean to mankind. This must be what Terry felt, he

thought.

For perhaps three hours he remained on the outside of the shell,

letting his mind idle under the brilliance of the stars. Suddenly, the

phones in his helmet came alive with sound. It was the voice of Terry

Bernard.

"We've got it, Del," he said quietly. "We can read this stuff like

nursery rhymes. Come on down. It tells us how to get into the thing."

Underwood did not hurry. He rose slowly from his sitting position and

stared upward at the stars, the same stars that had looked down upon

the beings who had sealed up the repository. This is it, he thought.

Man can never go back again.

He lowered himself into the opening.

Doctor Phyfe was strangely quiet in spite of their quick success in

deciphering the language of the Stroids. Underwood wondered what was

going through the old man's mind. Did he, too, sense the magnitude of

this moment?

Phyfe said, "They were semanticists as well. They knew Carnovan's

frequency. It's right here, the key they used to reveal their language.

No one less advanced in semantics than our own civilization could have

deciphered it, but with a knowledge of Carnovan's frequency, it is

simple."

"Practically hand-picked us for the job," said Terry.

Phyfe's sharp eyes turned upon him suddenly behind the double

protection of his spectacles and the transparent helmet of the

spacesuit.

"Perhaps," said Phyfe. "Perhaps we are. At any rate, there are certain

manipulations to be performed which will open this chamber and provide

passage to the interior."

"Where's the door?" said Underwood.

Following the notes he had made, Terry moved about the room, directing

Underwood's attention to features of the design. Delicately carved,

movable levers formed an intricate combination that suddenly released

a section of the floor in the exact center of the room. It depressed

slowly, then revolved out of the way.

For a moment no one spoke while Phyfe moved to the opening and peered

down. A stairway of the same glistening material as the walls about

them led downward into the depths of the repository.

Phyfe stepped down and almost stumbled into the opening. "Watch for

those steps," he warned. "They're larger than necessary for human

beings."

Giants in those days came to Underwood's mind. He tried to vision the

creatures who had walked upon this stairway and touched the hand rail

that was shoulder high for him.

The repository was divided into levels and the stairway ended abruptly

as they came to the level below the anteroom. The chamber in which

they found themselves was crowded with artifacts of strange shapes and

varying sizes. Not a thing of familiar cast greeted them. But opposite

the bottom of the stairway was a pedestal and upon it rested a booklike

object that proved to be hinged metallic sheets, covered with Stroid

III inscriptions, when Terry climbed up to examine it. He was unable

to move it, but the metal pages were locked with a simple clasp that

responded to his touch.

"It looks as if we've got to read our way along," said Terry. "I

suppose this will tell us how to get into the next room."

Underwood and the other expedition members moved cautiously about,

examining the contents of the room. The two photographers began to make

an orderly pictorial record of everything within the chamber.

Standing alone in one corner, Underwood peered at an object that

appeared to be nothing but a series of opaque, polychrome globes

tangent to each other and mounted on a pedestal.

Whether it were some kind of machine or monument, he could not tell.

"You feel it, too," said a sudden quiet voice behind him. Underwood

whirled about in surprise. Phyfe was there behind him, his slight

figure a shapeless shadow in the spacesuit.

"Feel what?"

"I've watched you, Doctor Underwood. You are a physicist and in

far closer touch with the real world than I. You have seen me—I

cannot even manage an expedition with efficiency—my mind lives

constantly in the past, and I cannot comprehend the significance of

contemporary things. Tell me what it will mean, this intrusion

of an alien science into our own."

A sudden, new, and humbling respect filled Underwood. He had never

dreamed that the little archeologist had such a penetrating view of

himself in his relation to his environment.

"I wish I could answer that question," said Underwood, shaking his

head. "I can't. Perhaps if we knew, we'd destroy the thing—or it might

be that we'd shout our discovery to the Universe. But we can't know,

and we wouldn't dare be the judges if we could. Whatever it is, the

ancient Stroids seem to have deliberately attempted to provide for the

survival of their culture." He hesitated. "That, of course is my guess."

In the darkened corner of the chamber, Phyfe nodded slowly. "You are

right, of course. It is the only answer. We dare not try to be the

judges."

Underwood saw that he would get nowhere in his understanding of

the Stroid science by merely depending on the translations given him

by Terry and Phyfe. He'd have to learn to read the Stroid inscriptions

himself. He buttonholed Nichols and got the semanticist to show him the

rudiments of the language. It was amazingly simple in principle and

constructed along semantic lines.

The going became rapidly heavier, however, and it took them the

equivalent of five days to get through the fairly elementary material

disclosed in the first level below the antechamber.

The book of metal pages did little to satisfy their curiosity

concerning either the ancient planet or its culture. It instructed them

further in understanding the language, and addressed them as Unknown

friends—the nearest human translation.

As was already apparent, the repository had been prepared to save the

highest products of the ancient Stroid culture from the destruction

that came upon the world. But the records did not even hint as to the

nature of that destruction and they said nothing about the objects in

the room.

The scientists were a bit disappointed by the little revealed to them

so far, but, as expected, there were instructions to enter the next

lower level. There, an entirely different situation confronted them.

The chamber into which they came after winding down a long, spiral

stairway, narrow, yet with the same high steps as before, was spherical

in shape and seemed to be concentric with the outer shell of the

repository. It contained a single object.

The object was a cube in the center of the chamber, about two feet on

a side. From the corners of the cube, long supports of complicated

spring structure led to the inner surface of the spherical chamber.

It appeared to be a highly effective shock mounting for whatever was

contained within the cube.

The sight before the men was impressive in simplicity, yet was

anticlimactic, for there was nothing here of the great wonders that

they had expected. There was only the suspended cube—and a book.

Quickly, Phyfe advanced along the narrow catwalk that led from the

opening to the cube. The book lay on a shelf fastened to the side of

the cube. Phyfe opened it to the first sheet and read haltingly and

laboriously:

"Greetings, Unknown Friends, Greetings to you from the Great One. By

the token that you are now reading this, you have proven yourselves

mentally capable of understanding the new world of knowledge and

discovery that may be yours.

"I am Demarzule, the Great One the greatest of great Sirenia—and the

last. And within the storehouse of my mind is the vast knowledge that

made Sirenia the greatest world in all the Universe.

"Great as it was, however, destruction came to the world of Sirenia.

But her knowledge and her wonders shall never pass. In ages after, new

worlds will rise and beings will inhabit them, and they will come to a

minimum plane of knowledge that will assure their appreciation of the

wonders that may be theirs from the world of Sirenia.

"You have minimum technical knowledge, else you could not have created

the radiation necessary to render the storehouse penetrable. You have a

minimum semantic knowledge, else you could not have understood my words

that have brought you this far.

"You are fit and capable to behold the Great One of Sirenia!"

As Phyfe turned over the first metal sheet, the men looked at each

other. It was Nichols, the semanticist, who said, "There are only two

possibilities in a mind that would write a statement of that kind.

Either it belonged to a truly superior being, or to a maniac. So far,

in man's history, there has not been encountered such a superior being.

If he existed, it would have been wonderful to have known him."

Phyfe paused and peered with difficulty through the helmet of the

spacesuit. He continued, "I live. I am eternal. I am in your midst,

Unknown Friends, and to your hands falls the task of bringing speech to

my voice, and sight to my eyes, and feeling to my hands. Then, when you

have fulfilled your mighty task, you shall behold me and the greatness

of the Great One of Sirenia."

Enright, the photographer said, "What the devil does that mean? The guy

must have been nuts. He sounds like he expected to come back to life."

The feeling within Underwood was more than bearable. It was composed

of surging anticipation and quiet fearfulness, and they mingled in a

raging torrent.

The men made no sound as Phyfe read on, "I shall live again. The Great

One shall return, and you who are my Unknown Friends shall assist me to

return to life. Then and only then shall you know the great secrets of

the world of Sirenia which are a thousand times greater than your own.

Only then shall you become mighty, with the secrets of Sirenia locked

in my brain. By the powers I shall reveal, you shall become mighty

until there are none greater in all the Universe."

Phyfe turned the page. Abruptly he stopped. He turned to Underwood.

"The rest of it is yours," he said.

"What—?"

Underwood glanced at the page of inscription. With difficulty he took

up the reading silently. The substance of the writings had changed and

here was a sudden wilderness of an alien science.

Slowly he plodded through the first concepts, then skimmed as it became

evident that here was material for days of study. But out of his hasty

scanning there came a vision of a great dream, a dream of conquest of

the eons, the preservation of life while worlds waned and died and

flared anew.

It told of an unknown radiation turned upon living cells, reducing them

to primeval protoplasm, arresting all but the symbol of metabolism.

And it spoke of other radiation and complex chemical treatment, a

fantastic process that could restore again the life that had been only

symbolized by the dormant protoplasm.

Underwood looked up. His eyes went from the featureless cube to the

faces of his companions.

"It's alive!" he breathed. "Five hundred million years—and it's alive!

These are instructions by which it may be restored!"

None of the others spoke, but Underwood's eyes were as if a sudden,

great commission had been placed upon him. Out of the turmoil of his

thoughts a single purpose emerged, clear and irrevocable.

Within that cube lay dormant matter that could be formed into a

brain—an alien but mighty brain. Suddenly, Underwood felt an

irrational kinship with the ancient creature who had so conquered time,

and in his own mind he silently vowed that if it lay within his power,

that creature would live again, and speak its ancient secrets.

"Del!" The shock of surprise and the flush of pleasure heightened the

beauty of Illia's delicate features. She stood in the doorway, the

aureole of her pale golden hair backlighted by the illumination from

within the room.

"Surprised?" said Underwood. He always found it difficult to speak for

a moment after the first sight of Illia. No one would guess a beauty

like her to be the top surgeon of Medical Center.

"Why didn't you let me know you were coming? It's not fair—"

"—not to give you time to build up your defenses?"

She nodded silently as he took her into his arms. But quickly she broke

away and led him to the seat by the broad windows overlooking the night

lights of the city below.

"Have you come back?" she said.

"Back? You put such a confusing amount of meaning into ordinary words,

Illia."

She smiled and sat down beside him, and swiftly changed the subject.

"Tell me about the expedition. Archeology has always seemed the most

futile of all sciences, but I've supposed that was because I could find

nothing in common between it and my medical science, nothing in common

with the future. I've wondered what a physicist could find in it."

"I think you'll find something in common with our latest discovery. We

have a living though dormant creature on an equal or superior plane of

intelligence with us. Its age is around half a million years. You will

be interested in the medical aspects of that, I am sure."

For a moment Illia sat as if she hadn't heard him. Then she said, "That

could be a discovery to change a world, if you're sure of what you've

found."

Underwood felt irritation more because he had been trying to fight down

the same idea himself than because she had spoken it. "Your semantic

extensions would turn Phyfe's whiskers white. We haven't found any such

world-shaking discovery. We've found a creature out of another age and

another culture, but it's not going to disrupt or change our society."

"If it's a scientifically superior culture, how do you know what it

will do?"

"We don't, but to apply so many extensions only confuses our

interpretation more. I mention it because we are going to need a

biological advisor. I thought you might like to be it."

Her eyes were staring far out across the halo of the city's lights. She

said, "Del, is it human?"

"Human? What's human? Is intelligence human? Can any other factor of

our existence be defined as human? If you can tell me that, perhaps I

can answer. So far, we only know that it is a sentient creature of high

scientific culture."

"Then that alone makes its relationship with us a sympathetic one?"

"Why, I suppose so. I see no reason why not."

"Yes. Yes, I agree with you! And don't you see? It can be a germ

of rejuvenation, a nucleus to gather the scattered impulses of our

culture and unify them in an absorption of this new science. Look

what biological knowledge the mere evidence of suspended animation

indicates."

"All right." Underwood laughed faintly in resignation. "There's no use

trying to avoid such a discussion with you, is there, Illia? You'd take

the first flower of spring and project a whole summer's glory from it,

wouldn't you?"

"But am I wrong in this? The people of Earth need something to cement

them together in this period of disillusionment. This could be it."

"I know," said Underwood. "We talked it over out there before we

decided to go ahead with the restoration. We talked and argued for

hours. Some of the men wanted to destroy the thing immediately because

it is impossible to forecast the effect of this discovery from a

strictly semantic standpoint. We have no data.

"Terry Bernard definitely fought for its destruction. Phyfe is afraid

of the possible consequences, but he maintains that we haven't the

right to destroy it because it is too great a heritage. I maintain

that from a purely scientific standpoint we have no right to consider

anything but restoration, regardless of consequences.

"And there is something more—the personal element. A creature whose

imagination and daring were great enough to preserve his ego through an

age of five hundred thousand years deserves something more than summary

execution. He deserves the right to be known and heard. Actually, it

seems ridiculous to fear anything that can come of this. Well, Phyfe

and Terry are expert semanticists, and they're afraid—"

"Oh, they're wrong, Del! They must be wrong. If they have no data,

if they have only a hunch, a prejudice, it's ridiculous for them as

scientists to be swayed by such feelings."

"I don't know. I wash my hands of all such aspects of the problem.

I only know that I'm going to see that a guy who's got the brains

and guts this one must have had has his chance to be heard. So far,

I'm on the winning side. Tomorrow I'm going to see Boarder and the

Director's Committee with Phyfe. If you're interested in taking the job

I mentioned, come along."

The enthusiasm of the directors was even greater than that of Illia,

if possible. None of them seemed to share the fears of some of the

expedition members. And, somehow, in the warm familiarity of the

committee room, those fears seemed fantastically groundless. Boarder,

the elder member of the committee of directors, could not hold back

his tears as he finished the report and Underwood had given verbal

amplification.

"What a wonderful thing that this should have happened in our

lifetime," he said. "Do you think it is feasible? The thing seems

so—so fantastic, the restoration of a living creature of half a

million years ago."

"I'm sure I don't know the answer to that," said Underwood. "No one

does. The construction of the equipment described by the Stroid,

though, is completely within range of our technical knowledge. I'm

certain that we can set it up exactly according to specifications. It

is possible that too much time has passed and the protoplasm has died.

It is possible that Demarzule thought in terms of hundreds of years,

or, at the most, a few thousand, before he would be found. There is

no way to know except to construct the equipment and carry out the

experiment, which I will do if the Directors wish to authorize the

expenditure."

"There is no question of that!" said Boarder. "We'd mortgage the entire

Institution if necessary! I'm wondering what laboratory space we can

use. Why not put it in the new Carlson Museum building? The specimens

for the Carlson can stay in the warehouse for a while longer."

Boarder looked about the circle of Directors facing him. He saw nods

and called for a vote. His proposal was upheld.

With approval given, Phyfe returned to the expedition to supervise

the transfer of the repository of Demarzule to Earth, while Underwood

began infinitely detailed planning for the construction and setup of

equipment as specified by the instructions he had brought from the

Stroid repository.

The great semanticist, Dreyer, was asked to help in a consulting

capacity for the whole project; specifically, to assist in

retranslation of the records to make absolutely certain of their

interpretation of the scientific instructions.