The Fixer

By WESLEY LONG

Illustrated by Kramer

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Astounding Science-Fiction

, May 1945.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Sandra Drake sat in her perfect apartment on Telfu, and cursed in an unladylike manner. She was plying a needle with some difficulty, and the results of her work were decidedly amateurish. But her clothing was slowly going to pieces, and there was not a good tailor in nine light-years of Sandra Drake.

The Telfan tailors didn't understand Solarian tailoring; Sandra was forced to admit that they were good—for Telfans. But for Solarians, they didn't come up to the accepted standards.

They had tried, she gave them credit for that. But the Telfan figure did not match the Solarian, especially the four-breasted female Telfan woman did not match Sandra's thin-waisted, high breasted figure. Her total lack of the Telfan skin; part feathers, part hair, but actually classifiable as neither, caused a different "hang" to the clothing. Telfans wore practically nothing because of the pelt and though Sandra's figure was one of those that should have been adorned in practically nothing, Telfu was not sufficiently warm to go running around in a sunsuit.

And making over Telfan clothing to fit her was out of the question. She stood half a head above their tallest women, and the only clothing that would have fit was clothing made in outsizes for extremely huge Telfan women. Needless to say this size of garment was shapeless.

Sandra finished her mending, tried on the garment and made a wry face. "I used to curse the lack of humans here," she told her image in the mirror, "but now I'm glad I'm the only one. I'd sure hate to have any of my old friends see me looking like this."

The image that repeated silently was not too far a cry from the Sandra Drake that had called the Haywire Queen in for a landing on Telfu some months ago. But they hadn't waited, and she now knew why. Well, she was forced to admit that her try at either trapping them here or getting off with them had failed, and therefore she had been outguessed.

That made her burn. Being outguessed by a man was something that Sandra didn't care to have happen. She could live through it; but it was the aftermath that really hurt. The Telfans came to understand her too well after that incident. They no longer looked upon her as a leading figure in her system. They knew that her knowledge of Solarian science was sketchy and incomplete. Therefore she had lost her hold upon Telfu, and was now forced to do her own mending.

On the other hand, Sandra Drake was an intelligent woman. Her contempt for the Telfan language was gone. It went on that memorable day when she discovered that everyone who understood any Terran had gone to greet the landing Haywire Queen and had left her unable to convey her desires. From that time on, Sandra plied herself and was quite capable of conversing in Telfan, and fluently.

So Sandra Drake had been living with the Telfans for several months. She had been forced to live with her wits and her mind and she found it interesting. Telfans were quite cold to her charms, which made her angry at times; on Terra she was used to admiration from anything masculine from fourteen to ninety-eight. Below fourteen they didn't know any better and over ninety-eight they didn't care, but the years between were aware of Sandra Drake. On Telfu, posturing, posing, and offering had no effect. They looked upon her as an encyclopedia; an animate phonograph, which, upon proper stimulation, could be made to sound interesting.

They had their machinery of action, too. Either Sandra assisted them—or she did not find things easy. It was adjustable, too, and the better assistance she gave, the better she found things.

Well, thought Sandra, it has been interesting—

She was startled by a knock upon her door. She admitted two Telfan men and a Telfan woman. The woman she knew.

"Yes, Thuni?" she asked the woman.

"Sandrake," announced the woman, putting the Telfan pronunciation on the Terran name, "These are Orfall and Theodi, both of whom are among the leading medico-physicists of Telfu. They desire your help."

Sandra reflected quickly. After all, this ability to be of assistance did give her a sop to her vanity. The fact that as little as she really knew of Terran science she could assist, and at times direct, gave her first feeling of real self-assurance.

"I shall, if I can," she told them.

"You, in spite of your untrained mind, have been extremely valuable," Orfall said simply. "While you do not know the details, you at least have some knowledge of the channels of Terran science, and you may, and have, explained down which channel lies truth, and along which line of endeavor lies but a blank wall. That in itself is valuable."

"Another item of interest," said Theodi, "is the fact that the books left us by the Haywire Queen are ponderous and often obscure; they assume that we have a basic knowledge which we have not. You have been able to direct us to the proper place in them to find the proper answer to many of our questions."

"I see," said Sandra. All too seldom had anyone told her she was valuable and interesting. It had been more likely a statement of her headstrong nature, her utter uselessness, and her nuisance value.

"As you know, we of Telfu are slightly ahead of you in chemistry. Yet there are things in chemistry that can not be solved without an advanced knowledge in the gravitic spectrum that Terra has exploited. Perhaps it was the lack of a channel in the gravitic that drove us into higher chemical development; but we are planet-locked until your people return to remove the block."

"Go on," said Sandra impatiently. "I gather that you are in trouble of some sort?"

"We are, indeed. A plague of ... ah, there is no word for it in Terran"—he switched to Telfan, "Andryorelitis," and back again to Terran—"which is an air-borne disease of the virus type. No inoculation has been discovered, and no immunity zone can be established. Telfu is in danger of halving the population."

"Bad, huh?"

"It is terrible. It strikes unknown. Its incubation period is several days, and then the victim gets the first symptoms. Nine days later, the victim is dead. Unfortunately, the victim is a carrier of andryorelitis during the incubation period, and therefore isolation is impossible."

"Sounds like real trouble to me," said Sandra. "Will examination reveal it?"

"Of course," answered Orfall. "But what planet can examine the population daily?"

"I see the impossibilities. Then what do you hope? We have nothing that will combat it; knowing nothing of it in Sol would preclude any possibility. What can we do?"

"To return to chemistry," said Theodi, "I will explain. Our chemico-physicists have predicted the combination of a molecule which will combat the virus selectively. It is a complex protein molecule of unstable nature—so unstable, unfortunately, that it will not permit us to compound it. We have used every catalyst in the book, and nothing works. Follow?"

"I think so," said Sandra. "What keeps it from forming?"

"As I said, it is very unstable. The atomic lattice appears to be structurally unsound. That happens in a lot of cases, you know. At any rate, we can make this molecule—and have made it successfully. But its yield is less than four ten-thousandths of one percent, and the residue precipitates out in an insoluble compound that can not be reprocessed."

"Otherwise you would keep the process going until completion?"

"Precisely. If reprocessing would work, we could leave the batch to cook until all of it went into combination. Or we could add fresh 'mix' to the processing batch and make the process continuous. But the stuff is not re-processable. We must complete each batch, and then go on a long process of fractionation to distill the proper compound out of the useless residue."

"I can see that a process of that inefficiency would be bothersome," said Sandra.

"Not bothersome, Sandrake. Impossible. Imagine going into a project giving about .000,37% yield for two hundred-fifty billion Telfans. The required dose of the antibody is forty-seven milligrams. Call it fifty, for round numbers, Sandrake, and you get a total figure of one trillion, two hundred-fifty billion milligrams, or one million two hundred fifty thousand kilograms. At four ten-thousandths of one percent yield, we'd have to process something like three hundred billion kilograms of raw material and then rectify it through that long and laborious process of fractional crystallization, partial electrolysis, and fractional distillation—with a final partial crystallization. Processing that much raw material would be a lifetime job at best. Doing it under pressure, with the planning and procurement problems intensified by the certainty of the few short weeks we have ... ah, Sandrake, it is impossible."

"What is this trouble specifically?"

"The final addition of silicon. It will not enter the compound, but forces something less active from the combination."

"Making it useless?"

"Right."

"You've tried it?"

"And it works," nodded Orfall.

"And knowing that you of Terra have some wonders in science, we would like to know—"

"You see," interrupted Orfall, "they've figured that the catalyst would be less than sixty-one percent efficient, if we could combine the silicon with it and let it replace into the other compound. That would work. But again we are stuck. The catalyst is stable as it is. What has Terra done to assist in forcing combination in unstable compounds?"

"Must be something," said Sandra, thoughtfully. "May I have a moment to think?"

"Certainly."

"And one thing more. Haven't you anything that even resembles tobacco on this sterile planet?"

"I'm afraid not," said Theodi. "Believe me, we have sought it."

"Thanks," said Sandra. "I know it was for me. But, fellows, I think better with a cigarette."

"We have analyzed the one you gave us, and haven't found a similar weed—"

"O.K., I'll do my thinking in a higher plane," smiled Sandra.

A thought, fleeting as the touch of a moth's wing, crossed Sandra's mind. She fought to reclaim it. It had some association with an experience—some experience in which she had failed, somewhere.

Recently? It might have been.

Long ago?

Sandra didn't think so.

She sat there silent, and the Telfans left with a short statement to the effect that she might be able to think better alone. They would return later.

It had to do with something highly scientific; something of a nature that staggered her imagination. It was coupled with something vast, something deep, something complex.

Her eyes fastened on a spot of brilliant light, reflected from a polished and silvered glass vase at her bedside, and as she sat there with her eyes unseeing, deep in concentrated thought, her mind focused upon the one thing of vastness that she had been involved in.

Sandra's mind was good, in spite of her inferiority complex. It was sharp, retentive, and above all, imaginative. It is a point for speculation whether the imaginative qualities might not have been responsible for her antics; certainly her escapades were the result of some imaginative desire to excel. At any rate, she fastened her eyes on the spot of light, and concentrated herself into a partial self-hypnosis. The train of thought went on before her unseeing eyes with the vividness of a color moving picture, and she was not living the scene, but seeing herself live through a train of events that seemed to jump the unimportant parts like a well-planned motion picture.

Her semihypnotized mind seemed to know the right track, though Sandra's wide-awake mind either ignored the key to the problem or was not certain of the right path to follow.

She was in a room of steel. Steel and machinery and gleaming silver bars. There was some chaos there, too. The silver busbars had lost their die-straightness, and in one place, a single lamination of the main bus hung down askew. It was about a foot wide and one inch thick, and the nine-foot section that hung from the ceiling was slightly lower than the top of her head.

There was blood on the sharp corner, and Sandra looked down to see the red splotch on the floor. She shuddered.

Cables ran in wriggly tangles across the floor. Some were still smoking from some overload, and others, still new from their reels, were obviously part of a jury-rigged circuit. Boxes of equipment were broken open and their contents missing, though the spare parts in the boxes were intact. The whole scene spelled—

Trouble!

The floor was not level; a slight tilt made standing difficult, until a man from some other room shouted:

"The mechanograv is working—hold on!"

And the floor rotated until it was the usual, level platform. The huge busbar swung gently on its loose mooring like a ponderous, irresistible mass.

And there was a man who came striding in. His contempt for her still hurt, and Sandra winced. Even in that motion-picture dreaming, wherein the girl in the picture seemed apart from Sandra Drake, the ire vented upon the red-headed image made Sandra writhe in sympathy.

And then she heard the words come from the man's lips. They were clear and concise, and seemed to come from the man himself instead of from within her own memory:

"The electronic charge is great enough to force an inert element—xenon—to accept an additional electron in its ring-system. This permits combination with active elements such as bromine. When xenon-bromide forms, we know that our intrinsic charge is highly electro-negative. See?"

The scene within Sandra's mind dissolved, and she shook her head. It cleared, but the words remained.

"Orfall," she called. "Theodi! Thuni—bring them here!"

They returned. "McBride," she said. "He can do it!"

"How?" asked Theodi skeptically.

"You've read their books," said Sandra Drake. "You know the principle of the Plutonian Lens—and also that the alternating stations require terrible electronic charges to maintain the lens that focuses Sol on Pluto. They check that with the formation of xenon-bromide for negative, and decomposition of tetrachloro dibromo-methane for the positive charge. They can do it."

"Can't they do it on a planet?" asked Orfall sadly.

"Not unless they can raise the whole planet to a high negative charge," snapped Sandra. "What do you think?"

"I don't know—none of us do. Can they?"

"No."

"Then—?"

"We'll call them, tell McBride what's the matter and what we need. He'll fix it."

"It sounds like a fool's gesture to me," said Theodi.

"Utterly impossible. How are we going to get in touch with them in the first place?"

"Look," said Theodi. "We can call them. See what McBride says and put the problem to them. If there's a way out, fine. If not, we've lost nothing."

"But how are we going to call them over nine light-years of space?"

"Ah—yes," said Theodi. "We can't."

"Maybe I can," said Sandra. "That'll be my contribution. I think I can call them."

"Nine light-years—" objected Theodi.

"Remember that the gravitic spectrum propagates at the speed of light raised to the 2.71828 ... th power. That'll make talking to Terra like calling across the room. May I try?"

"You think they'll be listening for you?"

"Can't miss," said Sandra with a positive gesture. "My ship, the Lady Luck, is equipped with the standard communications set. It puts out right in the middle of the main communications band of the electrogravitic. If I can get enough power to beam towards Sol, it'll hit them right in the middle."

"You intend to use the set in the Lady Luck?"

"Overloaded to the utmost. They tell me that they'll take one hundred percent overloads for an hour. Make that one thousand percent, and it may last ten minutes. Ten minutes is all I need to give them our trouble—they have recorders if McBride isn't there to hear it in person."

"Where are you going to get that power?" asked Theodi.

"From you."

"Impossible, Sandrake. You know that there is not sufficient power available to make such a program possible."

"Ridiculous. The resources of a planet are unmeasurable."

"Perhaps so," said Theodi. "But remember that our power, like Terra's power, is spread out all over the face. The transmission of power such as you will require would be impossible because the line losses will be greater than the power input. It might be possible to connect the networks together and draw the entire power output of Telfu into one district, but line losses would prohibit its operation."

"I only need ten minutes maximum," said Sandra.

"You're asking us to sacrifice—? You mean—overload every plant within efficiency-distance of your ship until it breaks down?"

"What have you to lose?"

"Can we do it?" asked Orfall.

"Of course," said Sandra. "You run your machinery at low load until it is running at ten times the velocity, and then I cram on the power. Momentum will carry me through."

"And if one machine goes, under that load, the entire district will go completely dead."

"Oh no," said Sandra. "The closer and most powerful one will not be used. That one will be used to talk to the boys when they arrive. They'll only have a distress signal, and the details must be held until they come investigating. They can't land, and so we'll have to tell 'em the story while they're in space. We'll need that power."

"Small consolation. Then Indilee will be an oasis of power in a radius of powerless country."

Sandra looked Theodi in the eye and said in a cold voice:

"Then go on out and die with the rest of your kind. What good will your machinery do you if you're all dead?"

"This is a democracy, Sandrake. We cannot just take the machinery and the equipment of others—even to save ourselves."

"How's your red tape factory?" she asked with a smile.

"Meaning?"

"Either you get those power plants or die. I don't care if you steal them, buy them, or borrow them. But get them—and quick."

"But there is a chance to save Telfu," suggested Orfall.

"Sensible fellow," smiled Sandra. In her mind she cursed the whole planet. This was a place for Sandra to undulate a bit; to turn on those two-million kilovolt-ampere eyes; to stretch one rounded arm out straight, putting the other hand below the ear and raising the elbow to a level just above those eyes and shielding the victim from the warmth in them. This showed off Sandra's svelte figure to perfection, and few men in Sol could have refused Sandra anything after that perfect performance.

But they were very few.

The Telfan ideal of beauty did not include Sandra Drake's perfection. She could have postured from now until galaxy's end, and they wouldn't have known her intent. Against their women, Sandra was alien—not sickeningly ugly or deformed, but alien and acceptable—and totally undesirable.

Sandra sighed, told the subconscious mind not to bother with the spotlights and provocative sultriness, and tried to think her way to the mastery of these Telfans.

"Couldn't we divert the electrical supply plants across Telfu?" objected Theodi. "Seems to me—"

"Not a chance," said Sandra. "You have no idea of the power required. I must shoot the works all at once. The set, the generators, and the supply lines will all go out at once. That'll give me ten minutes, I hope."

"But the dissipation of such power—Where can we collect it?"

"There's only one place on Telfu. That's in the power room of the Lady Luck. That is still intact?"

"Yes. Handled, inspected, photographed, and manipulated without driving power, of course, but it is still intact."

"Should be," commented Sandra wryly. "After all, my trouble was not being able to make the drive work. Couldn't get any push. Used up my entire stock of cupralum. So, do we?"

"I hate to say 'yes,'" said Theodi.

"Look," said Sandra, realizing something for the first time. "We have lots of gravitic machinery. Give me your useless power plants and I'll see that you get gravitic machinery to replace them."

"Um-m-m."

"Look, Theodi, you're used to thinking in Telfan terms—which means no gravitics. Think in Terran terms. You are no longer alone in the universe. You are in contact with a race that has gravitic power."

"Well—"

Sandra smiled. "Take it or leave it—and die," she told him. "Think of it. Andryorelitis comes like a thief in the night, giving no warning. Like the black wings of a gigantic, clutching bat, silent and ominous and unseen it comes and spreads its horde of hell on the city. Men go on in their way, meeting other men and inoculating them, passing the germ of death to whomever the black visitor may have missed on his visit. Men take it to their families and spread it from hand to hand, from lip to lip, from mother to babe to grandparent and beyond. The unborn is as cursed as the almost-dead, for it is within their bodies. The days pass in which every soul is given the opportunity of catching and spreading the dread disease.

"Then in this peaceful, unawareness of the terror, nine days pass and one sees a red spot on his arm. He shies away from his friends not knowing that they, too, have red blotches. The city is made of slinking men, ashamed women, and scared children. The newspaper headlines scream of the plague, but none will buy, for they fear inoculation on the part of the newsboy. They fight and fear one another, and the plague has its way, spreading across the city like the falling of night and missing none.

"The Grim Reaper swings his sharp scythe, and the populace falls like shorn wheat.

"And the stricken city becomes a place of horror. The smell of rotting bodies taints the air and makes life impossible for those unlucky few who have not been given the peace of death. None are interested in the cries of the dying, and no one sees the sunken cheeks, the withered bodies, the redding flesh. Do you like that picture, Theodi?"

"You speak harshly, Sandrake."

"You paint a prettier one," said Sandra, scorning him. "Go home and dream. Let your imagination roam—or haven't you Telfans got imagination?"

"We have, but—"

"You utter fool! To stand there like a stick of wood between Telfu and some lumps of worthless metal! Like the drowning man that clutched his gold—which pulled him under. Fool's gold. Theodi."

"There is much in what she says, Theodi," added Orfall.

"It is hard to think, sometimes," said Theodi slowly.

"Men!" sneered Sandra. "The whole sex is the same, here or on any inhabited planet. You know so much! Your vaunted power of reasoning is so brilliant. You pride yourselves on your inflexible wills or your willingness to accept new ideas, depending upon which your utter self-esteem thinks is best to exhibit at the instant. Thuni, what do you think?"

"The metal is of little importance to dead men," said Thuni promptly. "And you claim that Terra and Pluto have machines in abundance. The answer is obvious."

"You see?" said Sandra triumphantly.

"I've forgotten," admitted Theodi. "I'd been taught from childhood that high power was hard to get. It is hard to think that another star has it a-plenty and is willing, and able, to give us enough for our needs. It is a revolutionary thought and seems unreal. A story, perhaps. Yes, Sandrake, you shall have your power."

"Good," said Sandra, taking a deep breath. "And thanks. I'll also need your best students for the job."

"Our best are poor enough. Gravitics were known in theory only. A detectable phenomenon, utterly useless. We could not pass the initial doorway—the power generating bands—because of our satellite's absorption of the primary effects. To study the higher and more complex effects was impossible save in theory. But you shall have them."

"I have some practical working knowledge of the stuff," said Sandra. "One can't live and work with McBride and Hammond and the rest without getting a bit of it. Oh, I was only with them for a few weeks at best, but they are ardent teachers. I'll get along with the help of your students."

"You're certain?"

"Not certain—but fairly sure. At best, you have nothing to lose and everything to gain."

"I think we have misjudged you," said Theodi. "You're fundamentally fine—"

"Thank you," said Sandra, simply. "Convincing you was the hardest job I've ever done, believe me."

"Convincing the Terrans—?"

"Will be the second hardest job. Darn it, we can't use television."

McBride shook his head at Steve Hammond. "Don't believe it," he said.

"You don't."

"No, I don't. Drake has something up her sleeve."

"It's a pretty big sleeve, then," grinned Hammond. "Rigging anything to call from Telfu to Sol is no small potatoes."

"She overloaded everything in sight. That'd about make it right," said McBride. "It went blooey right in the middle of the third sentence—'McBride or Hammond: Telfu in grip of serious epidemic. Need highly charged laboratory to prepare mis-valenced compound for synthetic serum. Danger is imminent, so implore your help for the lives of—' and that's all. Either she's as dramatic as Shakespeare, or this is the real juice."

"And you think it is joy-juice."

"Her past record—and yet we can't afford to pass this up. She should know, though, that if this is the malarkey, she'll be scorned out of the system. Both systems."

"She wrecked the lens—and she's still here," reminded Hammond.

"'Here' is right," said the pilot cheerfully. "In case you birds are wondering about our position, Telfu is right below us by ten million miles."

"Suppose she's got anything left of that set?" asked McBride.

"Imagine so. The thing couldn't have gone to pieces like the Wonderful One Horse Shay. Give a call and see. If Sandra's not kidding, she'll be listening."

"Kidding or not," laughed McBride, "Sandra will be listening."

Hammond turned on the communications set and coughed into the microphone, watching the meters swing. Then, satisfied, he said: "This is the Haywire Queen answering S. D. I. from Telfu. Calling Sandra Drake. If you are listening, break in. This is Hammond of the Haywire Queen listening for a repeat of previous S. D. I." Hammond broke into Telfan and repeated the message.

Then the answer-light winked on the panel and he heard:

"This is Sandra Drake. Is it really you?"

"No," said Hammond. "Just a reasonable facsimile. What's the matter?"

"Oh!" said Sandra. There was a world of feeling in the word. "This has been the longest seven days in my life. It worked, then."

"What worked then?"

"The communications set."

"Obviously. What did you do to it?"

"Not much, personally. I sort of managered it, though. They lent me their best gravitic students and we went to work on the thing. We remade everything in the set—everything that could stand it, that is—about four times their size. That's where I came in. Some things couldn't be increased in size without ruining the tuning, and I knew which ones. Is my output all right?"

"Shaky, but strong enough for service."

"I'm running without an output stage. We used the output stage to drive a super-power stage made of the beefed-up parts and when the works went blooey, it took the Telfan output and my output with it. I'm running off to my own driver stage."

"You've been a busy little girl," said Hammond. "What did you use for power?"

"I talked them into giving me every power plant in the district so that I could call you. It all went in eight minutes flat. The Lady Luck is a mess—again."

"Are you brave or foolish?" asked Hammond.

"Both," answered Sandra. "After all, this is no tea party. There isn't a good generator on the Lady Luck; I ruined them all trying to call you. Can you understand how urgent this is?"

"I think so," said Hammond. "How did you wreck the whole shooting-match?"

"I used the gravitic generators to generate local fields and used 'em as communications-band reflectors. Part of it was theory on the part of the Telfans and part of it was ideas given me by your experiments with the super-drive. Anyhow, I'll bet that Soaky is fifty degrees hotter, now, with all the soup we put into the transmitter. That'll make your problem easier—hey?"

"Yup," smiled Hammond. "Just like the guy whose only reason for sending telegrams was that he hated to see the mail-carrier work so hard."

"Well, fifty degrees is one percent of the way, anyway."

"That's right," grinned Hammond. "But look, we're killing valuable time if this is as important as it sounds. What's needed?"'

Sandra explained.

"And you say the silicon won't combine? Shucks, we can do that all right," said John McBride.

"Fine."

"Our problem is delivering the goods."

"Why?"

"Name me a container that will carry the electronic charge."

"Oh? I was thinking—"

"Don't bother," said McBride. "There isn't anything better than ten million miles of pure and absolute space. She'll corona, and then arc, and then she'll assume the normal charge and the stuff will come unstuck again. And you couldn't possibly send every Telfan out into space for a treatment. There aren't enough years in a century to do that."

"First, we'll have to do away with Soaky," said Hammond.

"We can do that," said McBride. "The converted spacecraft are about ready. We can get 'em off in twenty-four hours. But landing this compound is the tricky job. How are we going to do it?"

"Let's assume that we can think of something and get the rest of this yarn. How do you feel, Sandra?"

"Tired, sort of. I've been busy."

"I gather."

"But this slight relaxation is doing me a lot of good. Is the Lady Thani with you? Her sister, Thuni, asked me to ask."

"She and her husband are on Terra. We didn't pass that way. But you may tell Thuni that they are well, happy, and being treated with Terra's best. Our main trouble is shooing away vaudeville agents, flesh merchants, and screwball politicians who either want to tie their wagon on behind or run their wagon up against."

"You'll never get rid of them," said Sandra. "Are they pointing with pride or viewing with alarm?"

"The pointers-with-pride hold a very slight majority."

"That's a fair sign."

"You're right. It is. Luckily, most of the newspapers follow the pointers-with-pride and the general feeling is that way. Most of the malcontents fear that Telfu will have a finger in the division of the universe and they are not going to get as much because of it. They think we should step in and run Telfu, or Telfu may step in and run us."

"We're far enough apart to save 'em the trouble," said Sandra. "But look, fellows, you're running back to Terra—or Sol, anyway. Can you bring me something the next time you come? Please?"

"If possible," said Hammond.

"I need cigarettes, and clothing. I look seedy. I'm frantic for a smoke; I know where you can buy a corpus delectable, dressed in old clothing, for a pack of smokes."

"Willing to sell your body for a mess of potash?"

"Just about. But remember the old one—Caveat Emptor!"

"Knowing you—I'll remember," laughed Hammond. "How have you enjoyed your visit?"

"So-so. It's been an experience. A lonely experience, believe me. I've had my troubles, and I've had my triumph. Aside from the complete lack of human companionship, it's been interesting enough."

"You mean male adoration?"

"Might as well admit it," said Sandra. "These birds look upon me as they might view one of those platter-lipped Ubangis. I'm not interesting nor disgustingly repulsive. Here I am, and I'd have been washing floors for a living if it hadn't been for the fact that I do have some experience and knowledge in gravitics. At least, I know where to find the answer."

"Well, take it easy, Sandra, and we'll be back. Look, I'm dropping a message-carrier with a radio spotter in it. It'll carry all of our spare cigarettes. Can't do much about clothing. None of us wear lace undies."

"I'll bear up," answered Sandra with a laugh. "Thanks."

"O.K., then, see you later."

"Right," said Sandra. "So long!" the set died, but before it went completely off, they heard her say to someone in the background: "You can turn the lights on again."

"What did she mean by that?" asked Hammond.

"I'll bet a cooky that they had the entire output of some city diverted into her communications set. After all, what with Soaky's absorption plus the normal power-gravitic communication, they'd do a lot of running on a waterfall plant, or a coal burning plant to make up for what we accomplish with a single machine in Sol. Our power took a beating, as far as we are from it, and we know what kind of power it takes to do anything with the gravitics on Telfu. Well, let's get going. This seems to be the beginning of Our Busy Week."

At Hellsport, on Pluto, twenty-four huge ships were grouped. They looked like the Devil's spawn; their upright ovoid shapes set in the glimmering background of the light that danced from the open-hearth furnaces of Mephisto. In the sky, the reflection glowed, and it was known for hundreds of miles as The Eternal Fire.

But the men that were arriving were too busy to notice the picture it presented. They were too close to that scene, although they had seen the photographs in the News From Hell and Sharon's Post, where almost identical pictures filled a whole page in the roto-gravure sections.

They kept arriving, these men who were going to Sirius to set up another Lens. They came from resorts on the Sulphur Sea near Hell and they all asked the reason. They came from Sharon, which lies across the River Styx from Hell, and they asked the same question. The hurried call sought men from their play-spots in the Devil's Mountains and from the vacation wonderlands of the Nergal Canyon. The Great Cave of Loki in the Æsir Plains lost a dozen or so, and Fafnir's Abyss no longer rang to the click of camera shutters as the group left for Hellsport. Vulcan, the frustrated volcano, felt the downward-moving footsteps of the seven who were studying the embryonic crater that was beginning to show signs of life under the heat of Pluto's synthetic sun; the men left eagerly to be on their way to Sirius, but they all prayed that the cold of Pluto's interior would remain cold until they returned.

The Hall of the Mountain King rang to their laughter as they returned to their hotel accommodations near Hellsport, and then again was silent as they went to Hellsport and made the last finishing touches on their equipment.

Just before take-off time, the old familiar cry of "Where's Carlson?" went the rounds until Carlson himself took up the general communicator microphone and called "Here, dammit!" and was informed that it was good because they couldn't start the lens without him. That cooled Carlson off, because it was true and all of them knew it.

Then the two dozen mighty ships lifted in the air above Pluto and headed for Sirius. They joined the Haywire Queen on her way from the Plutonian Lens, and after a few minutes of discussion—all done while accelerating at one hundred and fifty feet per second per second—they fell silent and started on the run to Sirius, nine light-years away.

The trip was made without mishap.

"Now," said McBride, through the general communicator, "in order that we understand, I'm going to repeat the general plan again.

"This is a problem different from the central heating system. We are not going to make a planet livable—we are going to destroy it! Honestly, it is but a satellite, but the problem is only made more difficult since it is harder to hit with a stellar beam. But enough of that, we've got the calculations necessary.

"We intend to burn Soaky. Our trick, then, is to set up the maximum possible heat-energy field around or on Soaky. Therefore a lens-system such as the Plutonian Lens is out of the question. Far better is a duplex system. We shall, therefore, send twelve of our ships to a point in space less than thirty million miles from Sirius. This will give us a solid-angle of considerable magnitude—a power intake, if you will—that will extract about all that we can handle.

"The front lens-element will cause the divergent rays from Sirius to become parallel or nearly so. We can't help but lose some.

"Now these parallel rays will hit the second element, which will be set up less than ten million miles from Telfu. That's about as close as we can get without losing our control due to Soaky's field-absorption. And it will focus the entire possible bundle of energy on Soaky. Unless Soaky is utterly impossible, we'll cook his goose. Right?"

The answer came with a laugh. Then someone asked about Soaky.

"Soaky," continued McBride, "is a satellite of Telfu. It is approximately one quarter million miles from the planet, and is invisible from Telfu, being less than a hundred miles in diameter. The Telfans, by means of crude gravitic detectors, have discovered Soaky plotted his orbit pretty well, and so we really have little to do."

Steve Hammond went to the microphone and laughed. "McBride is a master at the art of understatement," he said. "But my contribution to the art of eliminating planets is an anachronism. We have, on the Haywire Queen, one of the most useless things in the universe. I shudder to mention it, fellows, but there must be some good place for everything, no matter how useless it may seem. We—and hold your hats—have a rocket ship."

A series of groans and catcalls returned over the communicator, and there was the shrill whistle of someone outrageously murdering "La Miserere."

"Yep," continued Hammond, "Skyways, who boast that they can furnish transportation anywhere within reason or realm of operating practice, have furnished the Pyromaniac, which, named, appropriately, may operate on or near Soaky. It is a useless bit of machinery for anything else, and once the Pyromaniac has landed on Soaky and planted spotter generators for us to get a precise 'fix' on, the Pyromaniac will be relegated to some museum—if she doesn't get scuttled on the way in."

At this point McBride returned and finished by saying: "We shall set up our lens, and exceeding Archimedes, 'Having a place to stand, we shall burn up a satellite.' So now go on and make the thing cook, fellows. You all have your orders. The Haywire Queen will be a roving factor, feel free to call us for any trouble. We've got our own job cut out for us."

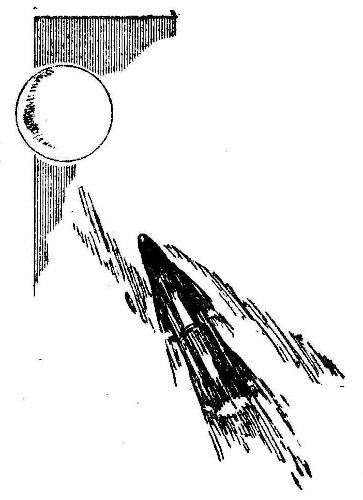

The twenty-four great ships of space, already spread out across the space between Sirius I and Telfu, began to jockey for their selected positions in space. McBride listened to the quick-running patter of the lens-technicians and the astrogators as they juggled their ships into the first semblance of order. Then he turned and nodded to Larry Timkins. Larry shook his head and left, going aloft to the rocket ship.

The loft opened and the Pyromaniac diverged from the opening. Hannigan, the Haywire Queen's regular pilot, snapped the switches briefly and the Queen darted away from the free-running Pyromaniac for several miles. Then the first burst of flame came searing out in a mushroom, which lengthened to a long rapier of white fire. The Pyromaniac moved off ponderously, and the sky was cut into two parts by the river of flame that burned in the rocket's jets. The rapier of flame curved slightly and pointed toward Telfu.

"No worrying about him," said McBride. "We'll know where he is."

"So will the rest of the system. O.K., Jawn, you've got the boys running—now for our problem. How do we make Silicon-acetyldiethyl-sulfanomid?"

"Yeah. How?"

"Well, according to La Drake, their trouble is the lack of stability. We can probably make it under high electronic charge—in fact, that's what she was suggesting."

"What'll it do when we remove the intrinsic charge? Remember the xenon-bromide. It falls apart when we leave the high negative."

"It's more than likely that the stuff will collapse when we neutralize."

"Do you suppose we could get it there before it falls apart?"

"You mean like the guy who used to put the light switch off and get into bed before it got dark?" laughed McBride. "What would happen to our xenon-bromide if we were to get it to zero charge all at once?"

"I don't know, but file that one away for future reference," said Hammond, thoughtfully. "Make up a batch of xenon krypto-neide, or any of that ilk which might be crystalline, and then heave it in an electrostatically charged shell at the enemy. Upon neutralization, what with the hellish electronic charge plus the reversion to gas—probably white-hot from electrical discharges—we'd have an explosive that would really be good."

"Good!" exploded McBride. "Look, my little munitions expert, the neutralizing charge—happening instantaneously—would paralyze everything electronic in nature for seventy miles even in space, and the electronic charge, reaching zero in nothing flat, would cause instantaneous decomposition of the compound. Since it is held together electrically, the decomposition, or burning rate, would propagate at the speed of light, or approaching that velocity. Whoooo. Blooey for everything in sight!"

"Funny how the human animal can always dream up a scheme for something lethal out of every invention."

"Yeah—even while they're trying to figure out something to save a planetful of people, they'll invent something deadly. That's one of the things that makes us us. But what do we do with the Telfans?"

"Theodi says it is stable once made—do you suppose it would be stable even if made in the forced process?"

"Let's try. Got the stuff?"

"Barrels of it," said McBride. He went to the shelves of bottles and removed the ingredients for Telfu's antibody. He weighed the chemicals, and placed them in a combustion boat. This he placed under a cover-glass and then called for Hannigan to run the intrinsic-charge generator.

As the collectors began to load the ship with electrons, and the various chemical indicators began to change color at various levels of charge, McBride and Hammond set up long-focus microscopes to watch the compound.

The final tube on the indicator panel changed from the mixture of xenon and bromine to a gray-green gas, and then McBride called: "Enough, Hannigan."

"Right, boss," said Hannigan.

"Any action?"

"Not yet. First the atmosphere of pure nothing so the stuff won't try to combine with the aforementioned atmosphere. Then twelve hundred degrees Kelvin, and finally the slow-cooling to form large crystals." McBride opened a valve and the trapped air under the sealed glass whipped out into space. "This stuff is stubborn," he added, turning on the heater. The mixture grayed a bit, and then started to turn cherry red all over at once. Hammond manipulated the color-temperature meter and when the color was right, he motioned and McBride cut the heater, riding the control all the way to room temperature.

"Anything?"

"Won't form."

"Huh?" asked Hammond. "I thought we could form anything."

"We can. But we might not live to tell about it. Some items of unstable planetary systems are easily converted from their normal valence-ratings to others of wide and ridiculous values. We picked xenon for our final indicator because it fits in nice with the negative value we need. But this stuff has valence-inertia beyond that value. According to this stuff here, I'd say that its instability was less than that of the carbon-chains that go into the human body."

Hammond whistled.

"And that means, little brother, that by the time we hit the right negative charge to make this stuff combine, we'll end up with being completely and irreplaceably dead."

"Ugh!" grunted Hammond. "Did we get anything?"

"Can't tell," said McBride. "Darned stuff sets like cement when it cools. Warm up the tensile strength machine and we'll crush it and paw through the wreckage."

He inspected the crushed mass a few minutes later and managed to separate two minute crystalline specks under the microscope. "I don't know whether these are the stuff, Steve," he said, "or whether it is just wishful thinking. Is it better than that four ten-thousands of one percent yield?"

"Not if you can weigh it. We started off with a hundred grams. One percent is one gram; four ten-thousandths of one gram is four hundred micrograms. The balance will swing over on less than ten micrograms. This isn't even that much. No good, Mac."

"Call Theodi and ask about that catalyst-conversion stunt."

"Huh?"

"He intimated that if they could combine the silicon with the catalyst, they'd be able to cause metathesis at better than sixty-one percent efficient. Trick is getting silicon to combine with an already-filled compound."

"They are better at chemistry than we," admitted Hammond. "I'll call."

Apparently the receiver in the Lady Luck was attended constantly, for the sleepy voice of a Telfan answered. He answered that he would get Theodi, and as he was about to shut off the transmitter, another voice came over. It was Thuni.

"Hello, Thuni," said Hammond cheerfully. "How goes it?"

"Bad," said the woman. "But I must go."

"I wouldn't," advised Steve. "Your sister Thani and her husband would like to talk to you."

"Oh," said Thuni in a strained voice. "I'd like to speak, too. But this expenditure of power ... I fear—"

"Nonsense. Thani has been nine light-years away for almost a year. Think, Thuni, the light that started from our star is only one ninth of the distance on the way, and Thani has been there and back."

"I know, but this power—"

"What's power?" laughed Hammond. "We've plenty of power."

"But we have not. Realize that the entire city of Indilee is in darkness because of my desire to speak."

"So what?" asked Hammond. "You have the chance, have you not?"

"But I am not Sandrake, who would think nothing of expending the entire power-availability of a whole city just to talk."

"Sandra is pretty much a human being in spite of her faults," said Hammond. "I'm certain that any of us would have done it, just in the same manner. In fact, I'm not too certain that Drake is inclined to be a little inefficient, not knowing too much about the finer points of operation. I'd probably divert the power output of the whole planet just to be sure I was heard."

"Does nothing stop Terrans?"

"Not for long," laughed Hammond. "And here's Thani. And the operator won't be asking for another thirty thousand dollars after the first three minutes, because there's no operator."

"I fear," started Thuni, and then ceased her worry. She finished: "I'll hold this open until Theodi comes, at least."

"Good. That's learning to use the gifts of the universe to your own comfort and pleasure. See you later, Thuni." To Thani, standing at his side, he said: "Here's your sister. She needs cheering up."

Thani flashed him a smile that might have been enticing in a Terran woman, and then turned to talk to her sister.

"Meanwhile," said McBride, "I've a thought. Not a good one, but a couple of dark ones. We know that silicon is a tough character. It doesn't take to planetary changes with the ease of xenon, for instance. It is way high up on the electronic-stability table."

"That's correct," said Hammond. "But we've been thinking in terms of not trying to add the silicon, but to combine the sulphur to the rest of the compound containing the silicon already."

"Frankly, not too much is known about the electro-combining processes with the more complex organic compounds. But what I'm thinking is this: A chain is as strong as its weakest link, and the attempt to add silicon to the compound only fails. When the more active sulphur is added, it automatically forces the silicon out of the compound, and will continue to do so until the right electro-negative charge is reached. Electro-combining silicon at a level less than its electro-stability level is impossible."

"That means trouble, Mac," said Hammond slowly. "Want to try the decomposition of silicon-fluoride?"

"Might, to kill some time." McBride reacted fluorine with silicon in a combustion chamber and then called for Hannigan to run the charge down again. They watched, and as they expected, nothing happened.

"That's it," said McBride. "We're stumped."

"I wonder—" mused Hammond.

"Have you any doubt? Are you thinking of automatically operated space-chambers set up for the formation of Silicon-acetyldiethyl-sulfanomid?"

"That might work if we had time to build 'em. But look, Mac. Suppose we generate a terrific electrogravitic field, monopolar as according to the first orders of gravitic fields. Generate this field in a volume of less than a foot in diameter, and accordingly intense. Then we'll negatize the ship, and at the same time bombard the electrogravitic sphere with electrons from a standard electron-gun. It'll take gobs of power, John, to drive 'em in, but the field will help, and also keep 'em there. What do you think?"

"Sort of localizing our collection of electrons, hey? Hm-m-m. We'll have to do that in vacuo—but that'll keep the atmosphere from combining, too, and is better as she goes. We have plenty of electrons when the ship runs negative, and that'll tend to collect them in the place where they're needed the most. Might work, Steve. Break out the E-grav and we'll try."

Hammond called Pete Thurman and James Wilson and told them what he wanted. They all set to work, but an interruption came for Hammond and Hannigan as the Pyromaniac returned in a blaze of fire.

The rocket went off, and the Haywire Queen's pilot did some fancy work until the inert rocket ship entered the space lock above. Larry Timkins emerged, holding his head between his hands. "It's murder," he said. "Downright murder!"

"What's murder?"

"Manipulating that fire-breathing gargoyle. Y'know how the regular drive takes hold all at once? Well, this thing sort of hangs fire. There's a bit of a lag—ever so little—since the jets are sheer mechanical and the time-function requires that the mechanical linkages from lever-turn to fuel-release, ignition, and ultimate movement—well, they act in considerably less time than the electrogravitic drive."

"Do you have to use it again?"

"Nope. I planted the spotter-generators and—picked up a souvenir of Soaky. Look," and he pulled a piece of crystal from his spacesuit pouch and dropped it on the table.

"Dirty looking hunk of glass," said Hammond. "Going to use it for a paperweight?"

"It'd go better on the gal friend's finger, but I'm going to sell it and lay away the profits for my edification and amusement. It'll assay four karats if it's worth a dime, and that ain't quartz."

"Diamond?" asked Hammond in surprise.

"It has an index of refraction higher than 2.4, and is harder than Sandra Drake's heart."

"Sounds like. How did it get there?"

"Ask the bird that dropped it. I only picked it up. If I'd found it in a blue-clay flue, I'd have mined Soaky for fair, but a loose diamond lying on the surface is strictly a changeling. Soaky must have known high-falutin' friends in his younger and more promising days. Call it one of those inexplicable mysteries and forget it. I give up."

"Hm-m-m. Might be more there, hey?"

"Yeah, but the life of Telfu depends upon our getting rid of Soaky."

Thani, who heard the latter part of the discussion, came over and looked at the uncut stone in wonder. "You will want to inspect our satellite?" she asked Hammond.

"I'd like to," he said. "But we have no time. While we've never synthesized anything larger than fractional-karat diamonds, and this four to five karats worth of crystallized carbon will be worth a small fortune to Timkins, here, the idea of forestalling help to Telfu whilst we chase a will-of-the-wisp is strictly a phony. Besides, it looks to us as though this one was a sport—an impossible find. Chances are that Larry was extremely lucky."

Thani shook her head. The chances of a huge fortune in precious stones going up the chimney because of danger to an alien race gave her food for thought.

McBride's shout cut all future conversation along this line. Hammond called for Larry to follow, and they went to the room in which the electrogravitic generator was being worked on.

McBride met them. "We're about ready," he said. "There's peepholes for all."

"Peepholes?"

"Unless you want to be in an airless room along with umpty-gewhillion electron volts. Better take a peephole."

McBride's hole was equipped with telescope and controls for the equipment. They set their eyes to the windows and watched. McBride explained: "First off, I open the space cock and let the vacuum of space in. Said vacuum drives the air out, leaving the place filled with hard nothing. That eliminates the possibility of corona with the voltages we are going to use."

Then he depressed the generator-on control button, and the pilot lights winked. He read the meters through the telescope, and adjusted the variable controls until a faintly outlined sphere formed between the radiator gravitodes of the generator. This sphere was invisible in that it reflected no light and was transparent, but the light from the wall beyond was refracted slightly, and the sphere was constantly changing in index of refraction, so that the sphere shimmered like heat waves over a meadow.

"We set the spherical warp, so. Now on the boom we insert the combustion tube containing the mix. The insertion of the boom is easy due to the heavy gravitic field, which attracts proportional to the square of the distance. I think it increases the inertia-constant—"

"Woah, Mac. Inertia is a property of matter, not a phenomenon."

"You can stir up a good argument later, here or at the annual meeting of the Gravitic Society. Right now I'm about to turn on the heat." McBride withdrew the boom, leaving the combustion tube in the warp, where it was fixed against the infinitesimal point of zero-attraction, with all sides of the boat in contracting-urge. He snapped the button and watched through the color-temperature meter. Then, as the color was reached, he threw over a series of controls, and the spherical field became a riot of color.

It fluoresced, as the bombardment of electrons hit it, coming from all sides. The sphere grew, and McBride tightened the warp by applying more power. Still it grew as the repulsion of the electrons tried to nullify the gravitic attraction, and McBride continued to step up the power of the electrogravitic generator to keep the sphere from expanding.

"Hannigan," he called. "Give me just a bit more?"

"We can stand about six more electrons," laughed Hannigan. "No more."

"Give 'em to me," returned McBride cheerfully.

And then the sphere refused to be confined. It grew, and McBride made comic motions with the hand that held the control, as if to turn the knob from its shaft in a supreme effort to increase the power by a single alphon.

The sphere grew to huge proportions, and McBride cranked the control to zero just as the surface of the sphere grew instable and threatened to expand without limit.

His other hand turned the heat control slowly down, and the color of the combustion tube died. A hiss of air entered, and they ran inside to see the result.

The combustion boat was ablaze with scintillating crystals. Beautiful blue-green crystals that were half-hidden in the gray-yellow powder of the catalyst. Their surfaces caught the lights, and sent little darting spots of blue fire dancing over the approaching people.

McBride lifted the combustion tube with a pair of tongs. "This is the pure stuff," he said quietly. "Looks like a good crop this year, too. What's it insoluble in, Steve?"

"Sulphur dioxide, according to Theodi."

"Good. We'll remove the catalyst with that and weigh the residue which will be the entire output of our hundred grams of stuff. The percentage will be higher than .004%, I'd say. Come on—"

The communicator barked: "McBride! McBride! This is Peters on Number One, Telfan element."

McBride answered: "What's the matter?"

"Nothing. We're in! We had a bit of trouble getting the warp going at this end. The image-size of Sirius when projected by a lens as close as the fore element is larger in diameter than Sirius is according to the distances involved, you know, and getting the warp started across the face of the Telfan Lens was some going. But we're about to thicken the center and shorten the focal length of the aft element right now."

"O.K. No trouble, hey?"

"Excepting it is hot in the hind-end stations. The interstices that give the spill-overs from Lens One do a swell job of heating up the stations when it hits."

"Sirius is hot stuff."

"Look, Mac, how much energy will it take to ruin Soaky?"

"Well," grinned McBride, "Lothar's 'Handbook of Useless Facts' says that a globe of ice the size of Terra, if dropped into Sol, would melt and boil so quick it wouldn't go 'Psssst.' Is Carlson handy?"

"Here, Mac. On the hind surface in the flitter and it is hotter than the hinges of Hell."

"The one on Pluto?"

"No, the one in the real Nether Regions."

"O.K., Carl. You're the balance wheel in this outfit. If you must aberrate, lean outward a bit, will you? I'd hate to singe the pants off of a couple of billion Telfans whilst trying to save their lives."

"I'll keep an eye on it," promised Carlson.

"Eye?" grunted Peters. "He means ear. Or has Carlson got his semicircular canals in his eyes?"

Hammond interrupted with a gloating shout. "Mac! We're in! Ninety-one percent. Pure, crystalline Silicon-acetyldiethyl-sulfanomid. And the charge is almost equal to the galactic mean; meaning that the stuff is stable."

McBride nodded and said into the communicator: "Our half is did, boys. All that stands between we-all and Telfu is a stinking, one-hundred mile satellite. Frankly, I'm agin it!"

Peters did not answer McBride. He shouted, his voice strained with excitement: "Here comes Soaky now, around the edge of Telfu. This is it, gang. Bore him deep and give him Hell!"

Sandra Drake sat down on the edge of a hard bench and took a deep breath. With her free hand, she rubbed her eyes and pushed the stray hair out of them. Her eyes were red-rimmed and puffed with lack of sleep. She stretched and took a longing look at the surface of the hard bench; one of those looks that was calculating not the hardness of the bench but wondering if she could catch forty winks without having trouble call her away again. She decided not. She knew herself, and she knew that as long as she kept going she could stay awake, but if she slowed down for a moment, she'd drop off and nothing would awaken her. And forty winks would actually make her feel worse than no sleep at all.

Outside of the window, dawn was just breaking. It was a strange dawn, an alien sunrise, but one that was nothing new to Sandra Drake. Sirius II was just above the horizon, but almost lost in the mists because of its low radiation. Sirius I was not above the horizon yet, but his strong radiation was coloring the sky blue-gray.

Sandra looked out of the window at the graying sky above. Carefully and hopefully she scanned it but she was not surprised that nothing was there for her to see. The idea of doing away with a hundred-mile satellite was too much, even for McBride, Hammond, and the rest of their gang. A hundred miles of celestial body was not large as celestial bodies go, but against man's futile efforts it was simply vast.

In all of the man-made works on Terra, Pluto, Venus, Mars, and Luna, considerably less than the volume of a hundred-mile sphere had been moved. Affected, perhaps, but not man-moved; the pile-up of rivers behind a dam could not be counted.

So man pitting himself against a celestial object seemed almost like sacrilege, though Sandra Drake knew that these men would take a job of analyzing the course-constants of the Star of Bethlehem if they thought they knew where it was now.

And as small as Soaky was against the giants of the galaxy, it was none the less a celestial object.

So she searched the sky hopefully and was not surprised that nothing was there. Her search was more "Will it happen" instead of "When will it happen?"

And then a Telfan stuck his head in the room and called: "Sandrake! Can you come?"

Sandra shook her head, rubbed her eyes again, and went.

"Now what?" she asked wearily. "We don't have to evacuate another district?"

"No," smiled Theodi, "not that bad this time. But we are going out to Loana—a small town not too far from here—and try out some of this latest stuff."

"Have any hope for it?"

"I must have hope," said Theodi.

"That's selling yourself a bill of goods," said Sandra.

"I know. But unless I play self-deception to the limit, I'll quit from sheer futility. No, Sandrake, I must hope with all my soul and I must force myself to believe that this may work."

"I won't even mention my friends," she said.

"You are beginning to give up?"

"I hate to think of it," said Sandra honestly. "It'll be the first time that they failed to do what they said they could do. I know they planned it, perhaps it takes longer than they think. Or perhaps they came unprepared; their equipment not complete. After all," and Sandra managed a reminiscent smile in spite of her feelings, "I've seen them running some of the haywirest equipment in the world and making it perform. Maybe this time the law of averages caught up with them."

"You think perhaps they are finding that our satellite is too much for them?"

"I hate to think of it. I'd hate to admit that they could fail."

"You have changed, Sandrake."

"Have I? I wonder if it is my hope that they will take me home. No, Theodi, in spite of what I may say about them, they know their potatoes. They're the typical genius-type. Whether they rate as genius I wouldn't know, but they're that kind of people. Give them a situation, and from somewhere in their memory they can bring forth the darnedest things which fit in like jigsaw pieces to complete the whole picture."

"I hope they continue," said Theodi. "Feel up to coming along?"

"Sure."

"Good. We need you."

"Who, me?" asked Sandra.

"Yes."

"Why?"

"Because you are alien. You are impartially alien. Though you have friends on Telfu, they are few, and in your secret mind you class us all as 'Telfan' and forget about sub-classifications. This experimentation is just that, to you, and we are the subjects. Therefore when you select one hundred victims out of a district, we get a perfect, impartial selection; a true cross-section of the district."

"Any of you could do that."

"No. We'd be biased by our knowledge of who is important, who is the sicker, who is young and who is old. And, though it may seem strange to you, you have absolutely no idea of beauty. Therefore you are impartial among the ugly and the beautiful."

"So what?"

"In experimentation on humans, we are inclined to pick those of less value to the community. We pick the lame and the halt and the ugly. We are inclined to pick those who are likely not to live anyway, and this biases our selection. Come, let's get going."

"O.K. Lead on."

Three hours later, and still without sleep, Sandra strode up the line of Telfans and pointed out one after the other. Those selected followed silently to the auditorium in the center of the village and seated themselves. They looked neither happy nor regretful, but rather a resignation was upon them.

Sandra said: "Is this the best place you could pick?"

"Sorry," smiled Theodi. "I didn't know it made any difference."

"I suppose it is good from a functional standpoint," said Sandra. "Being on the stage permits them to pass before us from one side to the other. It is the only clear place in the auditorium in which to work, and as far as I could see, there isn't any other suitable place in town. But being on the stage sort of makes me ... oh, come on. I'm just tired, I guess. Where's the pills?"

"No pills on this deal," said Theodi, opening a case and removing a set of large hypodermics. "This goes into the vein. Right in the main line. You'll have to help."

"Me? Look, Theodi, I don't feel well enough to go shoving needles into people."

Theodi looked up sharply. Her brash-sounding statement was made in a hard voice in spite of its humanitarian and pleading sound. Sandrake, to Theodi's opinion, was really feeling ill.

"It must be done," he said simply. "You fill and hand them to me."

Sandra took the first hypo, inserted it into the disinfectant, and then filled it from an ampule. She handed it to Theodi and watched him with fascination as he took the first Telfan in line and thrust the needle into his arm. It went in and in, and Theodi felt around with the needle-point until he found the vein, and then he emptied the cylinder. "Next!" he called, and so on until the hundred had been inoculated.

"Now," said Theodi, "we'll proceed to Dorana and do likewise."

Sandra was silent all the way to the next village, and as she started down the line of people, picking them out one by one, her face began to whiten.

Halfway through, Sandra stopped.

"Go on," urged Theodi.

"Go on?" screamed Sandra. "Go on? No!"

"But—"

"Go on and on and on and on and on?" shrieked Sandra in a crescendo that ended in a toneless, inarticulate screech. She stopped the sentence only because her voice had no more range and she had no more breath. "Theodi, I feel like a murderess! I go on selecting people as I would select specimens to be speared with a mounting pin and stuck on a cardboard. I point them out. They follow dumbly with a look of resignation. They come and you try something new on them—every time it is something new, and you don't know whether it'll kill 'em or not! I can't stand it."

"But who can we have to do this?"

"Get one of your own to do your own dirty work! You need me! Bah! Suppose—?"

"Suppose we have the right combination?"

"Suppose you have? You haven't—and you know it."

"I wouldn't say that."

"I would. You're just experimenting." Sandra's lip curled over her perfect teeth in a perfect sneer. "Experimenting on your own kind. And I'm no better. You should hate me—and I'm beginning to hate you and every one of you."

"This must go on—"

"It'll go on without me."

"Come on, Sandrake. Buck up. Here, I'll give you a sedative and you sleep for an hour. You're over-tired. Then—"

"Then nothing. I can't go on murdering your people any more."

"It's not murder. It's—"

"It's worse than murder. You go on filling them with colored water and telling them that you think that this is the works—and you know it is just another blind try! Go away!" Sandra whirled and ran blindly. Across the field she ran, out and away from the village. On and on she ran, until she fell breathless beside a small brook.

Thankfully, she dabbled in the brook with her tired feet, and laved the cool water on her wrists and forehead. She drank sparingly, and then stretched on her back to relieve the strained muscles that seemed to make her back arch almost to the breaking point.

Unknowing, Sandra relaxed as the ground supported her back, and with the suddenness of falling night, Sandra slept.

Her dreams were less restful than the sleep. They were filled with a whirling panorama of lights, disembodied faces, grinning, leering faces who watched long, brutal needles find the vitals of mute sufferers whose only visible admission of unbearable pain was the tortured look on their mobile faces. And through the dream, McBride and Hammond fought against a huge metal barrier against which their mightiest efforts were futile.

The day wore on as Sandra slept, and night came, and in all that time Sandra had hardly moved. As the darkness fell, she aroused enough to drink from the brook and settle herself in a more comfortable position. Afterward she did not recall awakening at all but she did select a thick thatch of soft moss the second time and she wondered about it later. And it was about midnight when Sandra awoke.

She was slept out, rested. But the self-hatred was still vivid. The dream had kept it there, and though her body was rested, her mind was still tired from the furious mental action that went on even as she slept.

She stretched, rolled over on her back, and considered her actions of before with distaste. That had been a spectacle, and she hated spectacles except when they made her appear in a better light. She searched the sky wearily, picking out Garna, which was Telfu's sister planet, and Ordana, the behemoth of the Sirian system, both of which were shining close to the bright Geggenschein of Sirius. Above her, she spotted the place where all Telfans watched—the spot where Soaky should be according to their calculations. It was not a spot, but an area, and Sandra scanned it in a futile manner.

Nothing yet.

A minute change in the sky along the horizon made her turn quickly, hopefully. She scanned the sky carefully, and yet she knew that looking at the starry curtain was futile unless the scene became so evident that it could not be missed. She could see nothing, and besides, Soaky was supposed to be above, not on the horizon.

She looked above again, but there was nothing to see. Puzzled at that—that something that had caught her attention along the horizon. She shrugged, and in trying to rationalize she admitted that it might have been a meteorite; and she knew that she was overanxious.

It was the same, she knew.

But was it? Was it?

Was it?

No, but what in the name of—?

Garna and Ordana and Geggenschein were gone from the Telfan sky. What was this? Why should planets disappear?

Planets were about as permanent as—but they must still remain, it was their light that was gone! Sandra shouted. McBride! The lens. In her mind she saw the scaled layout; Sirius, Telfu, the other planets, and Soaky, the satellite that was oh, so close to Telfu. Place two biconvex lenses, one near Sirius and one near Telfu—and any light from Sirius that could normally reach Telfu—and the planets in line from Sirius—would be cut off by the lens, refracted into the energy beam that would ultimately be focused on Soaky.

They'd started at last! Sandra looked upward into the area containing Soaky.

And as she looked, a mite of colored pinpoint appeared in the sky above. It did not rise into the incandescence, it leaped. It passed upward through the red, the orange, the yellow, and the blue with lightning-flash speed, and then settled down in color to an intolerable white. It seared the eyes, that microscopic speck, and its brightness made it appear huge.

Sandra shook her head and looked down. The darkness was fading, and sharp shadows of the low bushes and herself marked the ground. The stars beside Soaky began to fade to the eye, and as the brightness took on solar brilliance, it was like the sudden return of daylight.

A flicker of the light caused Sandra to look into that intolerable light again. No, Soaky was still going strong. But it was scintillating, now, and there were streamers of incandescent vapor leaving the coruscating nucleus that was Soaky.

Full against Soaky the Sirian beam drove, and the surface vaporized. The streamers were the high-temperature vapors of incandescent metal, being driven away from the tortured satellite by the radiation pressure of that intolerable brilliance. The vapors condensed in finely divided droplets of metal, but still floated away in lines and whorls.

The landscape around Sandra was in full light, now, and the shadows were no longer sharp. The boiling, blue-white vapors were rushing from the satellite at high velocity, and they spoiled the point-source of light. They danced and flickered in the sky, and as Sandra watched, a slight twinge of terror crossed her, and she caught her breath.

This was not right. This was—was defying God Himself. And Sandra, never awed by the men themselves, fell in fear before the visible evidence of their ability. It was not right, this utter destruction of a celestial body by man. Men were supposed to be motes—bacterium on the skin of an apple—not mighty motes capable of almost literally eating the apple that—not eating but destroying ruthlessly—the apple that was spoiling their barrel.

And Sandra, not even awed by the God of her people, prayed to Him in fear. Fear, because people of her race dared to tamper with the universe.

But then the light passed away, and no omnipotent lightning flashed across the universe to destroy it. The night fell again, and darkness, unspoiled, crowded the landscape leaving Sandra light-blind. She fumbled aimlessly in the darkness that was by contrast the utter blackness of no-light.

Sandra Drake was not alone in that. Half of the people on the planet of Telfu were blinking in the darkness; silently groping their way into their houses. Their tongues were stilled by the awesome sight.

Sandra brushed her tattered skirt and smiled. She was a long way from Indilee and she wanted to be there as soon as she could. She was beginning to feel the pinch of the months of loneliness; before, it was futility to lie awake at night and think of the touch of a human hand and the sound of a human voice. Yes, she even admitted to the desire for a bit of admiration, after all, it had been her meat and drink.

But now it was a dream about to come true. There would be people of her own kind. People who could laugh at the hardy jokes of her race, and appreciate the casual acceptance of doing absolutely nothing for periods of time. The verbal sparring and blocking would be there, too; the nice trick of forcing someone into a trap of his own making and springing it with—not double talk—but triple talk. The sound of people who could discuss both downright earthy things and high theory with the same words but with slightly different inflections in their voices, and be understood by others who knew both lines of talk.

She gave a short laugh. They would never know whether she did it from sheer altruism or because she was scared to death at the idea of being exposed to andryorelitis.

She blinked. The sky flared briefly ahead of her in a brilliant and colorful display of some auroral discharge. It illuminated one full quarter of the celestial hemisphere in flowing color. Sandra thought and remembered a man saying: "The charge on Station One is so great that at twenty thousand feet it would arc a million miles or more." The words and the distances were forgotten, and probably wrong due to her faulty memory for those details, but she did remember something of that nature.

Obviously, one of the Stations had landed with a load of Silicon-acetyldiethyl-sulfanomid. The not-quite-perfectly neutralized electronic charge must have ionized the upper air in a sprinkling corona.

From another corner of the sky, a similar flare of color flashed, and it was followed by flashes from near and far, each one creating a streaking display of celestial fireworks.

At the sight of that auroral display, Sandra's head went up, her shoulders went back, and there returned to her step a bit of that lilting walk. She smiled crookedly and then broke into that saucy grin. She set her foot on the road to Dorana, from where she could get a ride back to Indilee.

There were Terrans here, all right. Her Terrans that nothing ever stopped. They came—and brought the goods with them.

But—who brought them?

Sandra Drake.

Throughout the night, the flashing of the celestial fireworks told the whole planet that Terrans were bringing the needed drug to Telfu. And with each flash, as with each mile, a bit of the old Sandra Drake returned.

There were a lot of miles back to the Haywire Queen.

THE END.