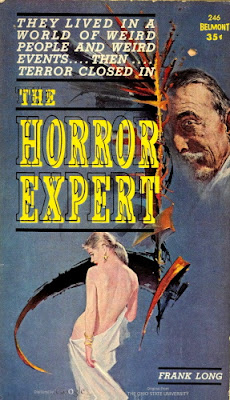

THE HORROR EXPERT

A New Novel by

Frank Long

BELMONT BOOKS

NEW YORK CITY

THE HORROR EXPERT is an original full-length novel

published by special arrangement with the author.

BELMONT BOOKS

First Printing December 1961

© 1961 Belmont Productions, Inc., all rights reserved

BELMONT BOOKS

published by

Belmont Productions, Inc.

66 Leonard Street, New York 13, N. Y.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TWISTED

"She had a secret library of psychological case histories, featuring pathological and brutal departures from normalcy in the area of sex. She never missed a weird movie. Terror in any form excited her physically...."

Helen Lathrup had a curious twist in her imagination ... a twist that needed an outlet in real life. Close friends found themselves drawn into a nightmare world of terror and guilt. Finally one violent act triggered an explosion.

"She's the kind of woman who can make a man hate and despise himself—and hate her even more for making him feel that way. I'm not the only one she's put a knife into. Do you hear what I'm saying, do you understand? I'm not her first victim. There were others before me, so many she's probably lost count. But she'll do it once too often. She'll insert the blade so skillfully that at first Number Fifteen or Number Twenty-two won't feel any pain at all. Just a warm gratefulness, an intoxicating sort of happiness. Then she'll slowly start twisting the blade back and forth ... back and forth ... until the poor devil has been tormented beyond endurance. He'll either wrap a nylon stocking around her beautiful white throat or something worse, something even uglier, will happen to her. I know exactly how her mind works, I know every one of her tricks. I keep seeing her in a strapless evening gown, with that slow, careful smile on her lips. She's very careful about how she smiles when she has the knife well-sharpened. It's a wanton smile, but much too ladylike and refined to give her the look of a bar pickup or a hip-swinging tramp. Brains and beauty, delicacy of perception, sophistication, grace. But if she were lying in a coffin just how many of those qualities do you think she'd still possess? Not many, wouldn't you say? Not even her beauty ... if someone with a gun took careful aim and made a target of her face."

The voice did not rise above a whisper, but there was cold malice and bitterness in it, and something even more sinister that seemed to be clamoring for release. It was just one of many millions of voices, cordial or angry or completely matter-of-fact that came and went in the busy conversational life of New York City. It might have come from almost anywhere—a quickly lifted and re-cradled telephone receiver perhaps, or from a recording on tape or from the recklessly confidential lips of a man or woman seated in a crowded bus, or walking along the street in the company of a close friend.

It might even have been addressed to no one in particular—an angry outburst prompted by some mentally unbalanced person's compulsive need to bare secret, brutally uninhibited thoughts.

But whatever its precise nature and from whatever source arising, it was quickly lost and swallowed up in the vast conversational hum of a city that was no stranger to startling statements and ugly threats.

Chapter I

The heat had been oppressive all night, but now the streets were glistening, washed clean by rain, and there was a holiday freshness in the air. The rain had stopped, but the taxi moving slowly down Fifth Avenue in the wake of the storm was still wet and gleaming and had the same washed-clean look.

The woman who sat staring out of the cab window at the cluster of pedestrians waiting to cross 42nd Street had dressed at leisure, eaten a light breakfast of orange juice, toast and three-minute eggs, glanced briefly at the morning headlines, and descended in a private elevator through a tall, gray house in the East Eighties without manifesting the slightest outward strain.

But once in the taxi a fierce impatience had taken possession of her—an impatience which far exceeded that of the pedestrians who were waiting for the Don't Walk light to vanish at New York's most crowded intersection.

Helen Lathrup had been chain-smoking and was now on her fourth cigarette. It was burning the tips of her fingers a little but she seemed not to care about the pain. She inhaled deeply, blew a cloud of smoke from her nostrils and fanned it away with her hand, her lips tightly compressed.

The hurry and bustle of shopgirls, clerks and early morning shoppers annoyed and angered her. She had no sympathy at all with the look of keen anticipation on many of the faces, for she was not in a holiday mood.

There was no reason why she should be, she told herself with considerable bitterness. The long Fourth of July week-end had not yet begun—was, in fact, a full day away. An interminable Friday stretched out before her, with important work piling up, work neglected or improperly handled, and there was no one except herself she could depend on to see that no mistakes were made.

It wasn't just the avoidance of costly stupidities she had to concern herself with. There were a hundred minor annoyances awaiting her. A grinning fool like Macklin, with his head in the clouds, could joke about them and call them "office headaches." But she knew that they could be serious, like grains of sand clogging the moving parts of a complex and very expensive machine.

She leaned forward and spoke sharply to the driver, gripping one nylon-sheathed knee so tightly that her knuckles showed white.

"What's holding you up? You waited too long at the last light, and now we're being stopped again."

"Sorry, lady," the driver said, without turning his head. "That's the way it is sometimes."

She leaned back, whispering under her breath: "Stupid man!"

"What did you say, lady?"

"Not a goddam thing."

Her mood did not improve as the taxi neared its destination, turning east a few blocks north of Washington Square and then west again, slowing down amidst a crosstown traffic snarl that seemed outrageous to her and entirely the fault of the police. She was lighting her sixth cigarette when the cab drew to the curb before a twenty-story office building with an impressive façade of gleaming white stone.

Ten minutes later Helen Lathrup sat alone in the most private of private offices, a sanctuary where interruptions were infrequent even when permitted, and intrusion under other circumstances absolutely forbidden.

The office was in all respects in harmony with the prestige and dignity of an editorial director of a nationally famous group of magazines. Large and paneled in oak, its main furnishings consisted of a massive oak desk, three chairs, one facing the desk, and a circular table with a glass top and nothing on it at all.

If the décor was a little on the severe side and there was something distinctly unbending about the woman who now sat facing the door upon which, in gilt lettering, her name was inscribed, a visitor entering the office for the first time would not have felt ill at ease.

Not, at any rate, if that visitor happened to be a man. Great feminine beauty, however much it may be combined with qualities intimidating to the male, is seldom intimidating at first glance. The glow, the warmth, the splendor of it is too instant and overwhelming. Even when it is allied with a harsh coldness which is quick to manifest itself, it is so very easy to believe that a miracle will occur, that secret delights are in store for any man bold enough to make light of obstacles which are certain to prove transitory ... if just the right technique is applied.

Though it is impossible to judge beauty by any rigid set of rules, though tastes may differ and the experts disagree, it is doubtful if one man in a hundred would have failed to be dazzled by the absolute perfection of Helen Lathrup's face and figure. She had only to cross a room, walking slowly and with no accentuation of movements which were as natural to her as breathing, to transport men into another world, where the sun was brighter, the peaks higher, and unimaginable delights awaited them.

Even in moments when she herself felt empty and drained, completely unstirred by the close presence of a man, there were few of her suitors who would not have stopped before a door marked "Danger—Enter at Your Peril," pressed a button, and walked into a room as chill and depressing as the gas chamber at San Quentin, solely for the pleasure of keeping a dinner date with her.

By whatever yardstick her friends or enemies might choose to judge her by, Helen Lathrup remained what she was—an extraordinary woman. And by the same token, extraordinary in her profession, with accomplishments which inspired admiration and respect, however grudgingly accorded.

There was another aspect of Helen Lathrup's personality which she seldom talked about and which made her unusual in a quite different way.

At times, her thoughts would take a very morbid turn; she would fall into restless brooding and seek out a kind of diversion which most people looked upon as pleasurable only when it remained completely in the realm of entertainment. To her, it was something more.

The darkly sinister and terrifying in literature and art disturbed and fascinated her. She had long been a reader of supernatural horror stories and there were a dozen writers in that chilling branch of literature to whose work she returned again and again. Edgar Allan Poe, Ambrose Bierce, M. R. James and H. P. Lovecraft—all supreme masters in the art of evoking terror—occupied an entire shelf in her library, along with scholarly studies of witchcraft, medieval demonology and Satanism.

Another shelf was entirely taken up with modern psychological studies of crime in its more pathological and gruesome aspects, including those often brutal departures from normalcy in the sphere of sex that appall even the most sophisticated minds.

She never missed an outstanding screen production of a terrifying nature. Mystery films which dealt with criminal violence in a somber setting never failed to excite her. The psychopathic young killer, haunted, desperate, self-tormented and guilt-ridden, had a strange fascination for her, whether in books or on the screen, and she experienced a pleasure she would not have cared to discuss as she watched the net closing in, the noose swinging nearer ... and then darkness and despair and the terrible finality of death itself.

But always there was a price which had to be paid. With the ending of the picture or the closing of the book a reaction would set in, and she would sit shivering, fearful, visualizing herself, not in the role of the furtive, tormented slayer—even when that slayer was a woman—but as the victim.

The victim of the very violence she had welcomed and embraced, with wildly beating heart, when she had thought of it as happening to someone else.

She could not have explained this aberration even to herself, and the impulse to succumb to it, to make herself agonizingly vulnerable by seeking out a certain movie or a certain book, would come upon her only at times.

This Friday morning, however, Helen Lathrup was in an entirely different mood.

She was almost trembling now in her impatience to get on with the day's work, to make every minute count, precisely as she had determined to do on the long, frustrating ride from her home to the office.

She picked up the mail which lay before her, looked through it, and leaned toward the intercom to summon her secretary. The door of the office opened then, and someone she was not expecting to see until later in the morning, someone whose presence at that exact moment was distasteful to her, stared at her unsmilingly and closed the door again very firmly by backing up against it.

The intruder made no attempt to apologize for the outrageousness of such behavior—made no effort, in fact, to speak at all.

The gun in the intruder's hand was long-barreled, black and ugly-looking and capped by a silencer. It was pointed directly at her. The intruder's eyes were half-lidded, but when the light in the room shifted a little the lids went up, disclosing a cold rage and a firmness of purpose that told Helen Lathrup at once that she was in the deadliest kind of danger.

It was not in her nature to remain immobile when a threat confronted her. Neither was it in her nature to remain silent.

She rose slowly, keeping her eyes trained on the intruder's face, displaying no visible trace of fear. Her voice, when she spoke, was coldly contemptuous and tinged with anger.

"Why are you pointing that gun at me?" she demanded. "What do you want? I'm not afraid of you."

Still without uttering a word the intruder grimaced vindictively, took a slow step forwards, raised the gun a little and shot Helen Lathrup through the head.

The gun's recoil was violent, the report quite loud. A silenced gun is not silent. It can be heard from a considerable distance. But the intruder appeared either willing to accept that risk, or had discounted it in advance as of no great importance.

Helen Lathrup did not cry out, and the impact of the bullet did not hurl her backwards, for the bullet passed completely through her head and the weapon had been fired at no more than medium-close range.

For an instant the tip of her tongue darted along the quivering, scarlet gash of her mouth, but the rest of her face remained expressionless. Her eyes had gone completely blank. It was as if tiny, weighted curtains, iris-colored, had dropped across her pupils, obliterating their gleam, making both eyes look opaque.

For five full seconds she remained in an upright position behind the desk, her back held rigid. A barely perceptible quivering of her shoulders and a spasmodic twitching of her right hand gave her the look, if only for an instant, of a strong-willed woman shaken by a fit of ungovernable rage and still capable of commanding the intruder to depart.

Then her shoulders sagged and she shuddered convulsively and fell forward across the desk, her head striking the desktop with such force that it sent an ashtray crashing to the floor. An explosive sound came out of her mouth, and her body jerked and quivered again, but less violently, and after that she did not move.

The door opened and closed, with a barely audible click.

Chapter II

The clicking of typewriters in two of the offices almost drowned out the sound of the shot. It was just a faint zing, with a released-pressure kind of vibrancy about it. A ping-pong ball striking a metal screen might have produced such a sound.

It was strange and unusual enough to make Lynn Prentiss look up from the manuscript she was reading and wrinkle her brow. If a fly had alighted on her cheek she might have paused in much the same way, startled, incredulous—asking herself if it really could be a fly. A fly in an air-conditioned office, with all of the windows shut?

The zing puzzled and disturbed her more than a fly would have done, because the mystery could not be instantly solved with a quick flick of her thumb.

The angry impatience, the annoyance with trifles which she had been experiencing all morning—an impatience which hours of manuscript reading had done nothing to alleviate—turned even so trivial an unsolved mystery into an infringement on her right to work undisturbed.

She blew a thin strand of red-gold hair back from her forehead, and sat for an instant drumming her fingers on the desktop. Then her woman's curiosity got the better of her. She arose quickly, piled the unread manuscripts on top of the blue-penciled ones and strode out of the office.

The clicking of the battered typewriter in the office adjacent to her own stopped abruptly and Jim Macklin, his collar loosened and his tie awry, called out to her.

"When you get through taking out commas, Monroe, there's something here you can help me with. Or maybe you should be more of the Bardot type. With that sweater you're wearing, it's hard to tell."

"What is it this time?" she demanded, pausing in the doorway, but making no attempt to smile. Then, the way he grinned, the boyish impulsiveness which made him seem out of place in a briskly efficient magazine office at ten in the morning, caused her face to soften.

It was insane, of course—that she should think of him in an almost maternal way. There was a dusting of gray at his temples and he was almost twice her age. But he was such a big bear cub of a man, with such a lost-orphan kind of helplessness about him at times, that he ignited the maternal spark in her.

She hoped it wasn't too bright a spark and that it didn't show in her eyes. She had a feeling that he could ignite it in other women, too, and knew it only too well and perhaps even traded on it. A man could go very far, she told herself with more cynicism than she ordinarily felt, if he could do that to a woman and be exceptionally virile looking at the same time.

"I could be wrong," Macklin said. "But I've a feeling that if you'd just bend over and breathe on this manuscript something wonderful would happen to it. Just the whiff of a really beautiful femme would do the trick. The guy has all kinds of complexes and plenty of painful hungers and I'm not sure the right girl is sitting beside him in chapter three."

"I bet there's a wolf pack on every page," she said. "I wouldn't be safe anywhere near a story like that."

"Nope, you're way off base, gorgeous. Just one guy. He's slightly beat, sure. But basically he's a romantic idealist. He's the kind of guy it would be hard to separate from a room in Paris overlooking the Seine. Wine bottles on the floor, tubes of half-squeezed-out paint scattered around, everything in wild disorder. Being human, with the hungers and all, he's been out on the Boulevard looking for—I blush to say it—a pickup. He's found one, but, as I say, I'm not sure she's the right girl for him. But judge for yourself. It won't take a minute."

"Very amusing, Jim. But I just haven't time right now."

"Make time. You've got all afternoon to work down to the last of your manuscripts. And this is sure to interest you. She's right there beside him, sitting on a rumpled couch. Her long blonde hair is falling down and her lips are slightly parted—"

"Well—"

"Get the picture? Not a morsel of food has touched her lips for two days, and there's a tragic hopelessness in her eyes. But pallor becomes her. She's prepared to make any sacrifice, but she hopes she won't have to. It could develop into a great love, and she's hoping he'll have the strength to be understanding and wait. All right. He may look cynical, but he'd no more think of making a pass at that girl without encouragement than I would."

"You'll get no encouragement from me, you grinning ape!"

"A man can dream, can't he?"

"He can do other things as well. I've learned that much about men just in the short time I've been reading the stories you've passed on to me for final editing. Honest writing—stark realism. Brother! I should be the last to deny that most of it is very, very good. Brimming over with artistic integrity. Strong writing you'll never find me objecting to. But I hope you realize I couldn't read stories like that day after day and remain a naïve little girl from Ohio."

"Now who's doing the kidding," Macklin said, with mock solemnity. "There are no naïve little girls in Ohio any more—or in Indiana or Idaho. TV has taken care of that. But why should I deny your accusation? No punches drawn, baby. That's how Hemingway got his start, remember?"

Some of the levity went out of her gaze and she shrugged impatiently. "How would you expect me to remember? His first book was published twenty years before I was born."

Macklin's grin vanished and a hurt, almost accusing look came into his eyes. "I was pretty sure you'd read it anyway. That's the fourth time you've flared up at me in three days. Do you have to catch me up on everything I say? If you were like Lathrup I could understand it. She has a compulsion to cut people down to size, men especially. Three or four sizes smaller than they actually are. It's very bad. I'm not passing a moral judgment on her, understand? I'm just saying it's bad."

"What are you trying to say, Jim?"

"That you're not like Lathrup at all. You never had a terrible scare when you were eight months old—or three years old. You were never left alone in the dark, in mortal fear, crying out for food and warmth and not knowing if help would ever come to you. According to the psychologists, that's what makes people behave the way she does. A tragic accident in childhood, something parents can't always help or be held accountable for. You've never had any such scare. But the way you've been catching me up the past few days—"

Lynn tightened her lips and started to turn away, anger flaming in her eyes. Then, as if realizing that the rebuke had been merited, she swung back to face him again and said in a weary voice: "Sorry, Jim. I guess I've been driving myself too hard. Everyone feels they have to when Lathrup is in one of her moods. She's been practically standing over me with a whip for a week now. You can't do your best work when you're under that kind of pressure. If she could only realize—"

"She realizes," Macklin said. "She's cutting off her nose to spite her face, but she can't help it. She won't wreck the concern, no danger of that. She's too skillful a manipulator. What she loses in one direction, she'll make up for in another. She knows just how to prevent the really big blunders that could prove costly. If we publish a few stories and articles that just get by under the fence, because she's kept us from exercising our best judgment, it will all even up in the wash. Gawd, how I'm mixing my metaphors."

Lynn suddenly remembered why she had emerged from her office in such haste and the mystery of the strange sound began to trouble her again. It was neurotic, of course, a haywire kind of curiosity that she ought not to have succumbed to. But whenever she started anything she liked to finish it.

She thought of asking Macklin to accompany her down the corridor, but almost instantly thought better of it. He'd probably laugh her concern to scorn and she'd taxed his patience enough already.

It was her baby and she'd better carry it—as far as the reception desk anyway. She'd ask Susan Weil, and if Susan hadn't heard anything she'd know she was being foolish. She'd go back and sit down and finish the pile of remaining manuscripts. She said goodbye to Macklin and went on her way.

There were three offices to pass before she reached the end of the corridor and turned into the small, reception desk alcove.

Three offices to pass ... pigeons in the grass. It sounded like something from Gertrude Stein, or some nonsense rhyme from childhood.

She amused herself by repeating it over and over, as most people are prone to do with snatches of song or meaningless limericks when they're under tension.

"Why should that sound have disturbed me so much?" she asked herself and got no answer.

One of the offices, behind which she suspected that Fred Ellers would be sitting with his tie off, not just awry as Macklin's had been, presented to her gaze only a frosted glass exterior. The door was closed and probably locked, for Ellers had a habit of locking himself in when he was hitting the bottle.

The second office, from which the sound of another clicking typewriter issued, was occupied by Ruth Porges, trim and immaculate in the stiff, tailormade suit she customarily wore as if it were some kind of uniform.

The third door was ajar and a very distinguished-looking individual sat behind it. Allen Gerstle, white-haired and bespectacled, spent a lot of time over his exposé columns. He had a rare feeling for beautiful prose, wasted perhaps at times, but Lynn knew that a good style was an asset, even when only the cafe society set was prepared to take it seriously.

Lynn found herself at the reception desk almost before she realized that she had completely traversed the corridor. Susan Weil was answering the phone, but she cupped the mouthpiece with her hand and turned from it when she saw Lynn standing at her elbow.

"Is there something—?" she asked.

"I heard a funny sound a few minutes ago," Lynn said. "It sounded like ... like...."

"I know," Susan Weil said, helping her. "I heard it too."

"Where do you think it came from?"

"How should I know?" Susan asked, annoyed by a furious buzzing from the switchboard.

Then the irritation suddenly went out of her eyes and she replied cooperatively. "From either Eaton's office or Lathrup's office. I didn't pay much attention to it. It wasn't the only funny sound I've heard around here. When Lathrup—no, I guess I'd better skip it."

"Why, Susan, for Pete's sake?" Lynn asked, smiling a little. "You know I wouldn't repeat it. You've as much right as we have to say what you think. With that graduate major in anthropology you're using as an excuse to spend the summer at a switchboard when you could just as easily—oh, well."

"It's simple work and I like it," Susan replied. "I could spend the summer on Cape Cod and just about squeeze by. But why do it? I like New York in summer and I can use a little extra dough, and I don't feel like secretarying for a stuffy old professor of anthropology. That answer you? When they give out prizes for curiosity—"

"Like Alice in Wonderland, you mean? Curiouser and curiouser. Okay, I plead guilty. I just happen to be interested in people."

"It's forgotten. I forgive you. About that sound—"

"Let me find out for myself. I've gone too far to turn back now. I may as well pull out all the stops and make an absolute fool of myself."

A moment later Lynn was standing before the closed door of Helen Lathrup's private office, wondering if she should knock and announce herself before entering.

She decided not to knock. Either way, Lathrup was sure to be furious and she didn't want to be told to go away.

She took firm hold of the knob and opened the door.

The first thing she saw was the glistening red stain on the floor immediately in front of Lathrup's desk, where blood from the wound in Lathrup's right temple had trickled down over the front of the desk to the floor.

Then she saw the blonde head resting on the desk, and the wound itself and the limp white hand dangling over the edge of the desk.

Lynn Prentiss screamed.

Frederick Ellers had locked the door of his office and was pouring twelve-year old Bourbon from a private-stock fifth into a paper cup when he heard the scream.

The glass door was thin, and he could hear the scream distinctly. But he could not identify the voice, even though it made him sit bolt upright in his chair, dead sober for an instant.

I'm not the only one, he thought. Someone else has stumbled on agony.

Then the mist came swirling back and his thoughts became chaotic again.

Fire me. Just like that ... snap of her fingers. You'd better stay away from me. That's what I told her. When I go out of here I'm through. Told her that too. Just because she was so damn mean ... so cold rotten mean.

Feelings? You'd search a long while ... never find ... woman so goddam.... Told her I was sorry. How about that? What'd she expect? Go down on my knees? Listen, wait a minute. Before I'd do that—

Fifty-seven years old. Look at me, I said. Fifty-eight after the next fifty drinks. Fifty-eight and a fraction. Old, old, old.

Fire me. Didn't get the facts straight. Little straight facts in a big important article. Facts ... facts. What are a few frigging facts anyway? I can still write well, can't I? Can't I? Good strong ... strongstraightforward writing.

Drink too much. Drink all the time. Always polluted. Who am I to deny it? I'll tell you who I am. Graduate Columbia School of Journalism. Twelve years on the New York Times, seven Herald Tribune, five....

Sish to all that. Switch to magazines. Big mistake. Big mistake ever to switch. Newspaper man. First, foremost and always. Should never have switched.

That guy down in Florida. Miami? No, hell no. Somewhere in Florida. Palm Beach? No, no, no. Where then? What's it matter?

Important writer, wonderful guy, Pulitzer Prize winner. Think of it—Pulitzer Prize winner. Older 'n I am. Sixty-five, maybe seventy by now. Couldn't keep away from the stuff. Drank, drank, drank—always polluted. Now he's asking for handouts. Sitting by yacht basin. Watching the big ones—half-million-dollar yachts. Never own a flat-bottomed skiff. Neither will I....

Ellers got swayingly to his feet, pushing the chair in which he'd been sitting back so violently that it toppled over with a crash that caused him to shudder and cry out, as if a leather thong had bitten cruelly into his flesh.

He grasped the desk edge with one hand and with the other made circling motions in the air.

All her fault! Vicious inhuman.... "Don't! Don't come near me, you bitch. Don't touch me!"

He continued to sway and gesture, his voice rising shrilly. "Bitch, bitch, bitch!"

Ruth Porges heard the scream and stopped typing. She sat very still, her hands tightening into fists. After a moment she swayed a little, but she made no attempt to rise. The old fear of facing anything even possibly harsh kept her glued to her chair.

It was a fact, a hard fact, that most men found Ruth Porges difficult and cold and thought of her as unemotional. But she wasn't that way now and hadn't ever been and never could be that way.

It was a lie, a falsification which she had never quite known how to refute. She had seen Lathrup refute it for herself when she was not in one of her moods, when she wanted a man to grab hold of her and bring his lips down hard on hers.

How often Ruth Porges wanted that too—and more. How often she'd wished herself dead, not having that, being forced to pretend that it wasn't important, to lie to herself about it and go on, day after day, living a lie. To go on knowing how men felt about her, and how horrible it was that they should feel that way, and how deeply, sincerely, terribly she wanted them not to look upon her as a reluctant virgin with ice in her veins.

She wasn't, she wasn't, she didn't want to be. Why couldn't they see that and understand? Why couldn't they see that she was a woman with a great wealth of understanding to offer a man, a woman with the blood warm in her veins, a woman who could free herself to....

A wave of bitterness, or returning rage almost impossible to control, searing, destructive, hardly to be endured, swept over her and she buried her face in her hands.

If only Lathrup hadn't—

Roger Bendiner. The only man who'd refused to be angered by her shyness, by her panic when the moment actually came and she knew that there was no escape and she'd have to—

Let him undress her. Yes ... yes. She could let herself remember it now, she could begin to bring it out into the open, with no fear of being laughed at and misunderstood. His rough hands on her shoulders and that look in his eyes....

It was like a night of lightning and thunder and you fled into the dark woods and you fled and were overtaken and stuck down.

But it was what she had always wanted, always longed for, a bursting wonder and you didn't care about the cruel, dark shafts of pain.

But with Roger alone. Because Roger wasn't just any man. He respected her and loved her and was not afraid to frighten her because he knew that there was nothing for her to fear.

Oh, why was she lying to herself, even now? She would never see him again. Even if he came back to her, and begged her forgiveness for what he had done, even if he swore that Helen Lathrup meant nothing to him, she could never forgive him. It was too late, too late now, too late for—

The desk shook with her sobbing.

He stood by the down elevator with a bulging briefcase under his arm, a pale, hatless young man with unruly dark hair and deepset, feverishly bright eyes. His features were gaunt, the cheekbone region looking almost cavernous beneath the heavy overhang of his brow. A strange face, a remarkable face, not unappealing, but different somehow—a young-old face with bony contours, strange ridges, and depressions, a shadowy ruggedness of aspect which some women might have greatly liked and others looked upon with disfavor.

He was staring now at the double glass door with its gilt lettering—hateful to him now. EATON-LATHRUP PUBLICATIONS. He had come out of that door for the last time, he told himself, with a sudden trembling which he was powerless to control. He was free of her at last and he'd never go back again.

If a man is born with just one kidney or a right-sided heart how can he hope to operate on himself and make himself resemble the general run of people?

She'd encouraged him, hadn't she? Given him the feeling that she did understand, did sympathize. She'd acted at first like another Thomas Wolfe had walked into the office.

Could he help it if he was one of the few, one of the chosen, a really great writer? It was tragic and terrible perhaps and people hated him for it, but could he help it?

If she felt that he had no talent why had she built him up at first? It didn't make sense. Why had she built him up and then tried to tear him down? Why had she attacked him with pages of criticism, carping, unreasonable, tearing the guts out of his manuscripts?

She'd made him feel like a high school boy flunking an exam in English composition. And what had happened once between them didn't mean anything. How could it have meant anything when she'd turned on him like that?

He closed his eyes again, remembering, and the torment within him increased. He could see her eyes again, level with his own, and feel the softness of her body pressed so close that it seemed to mold itself into his own flesh, and he could smell again the perfume she'd worn, and taste the sweetness of her lips....

The elevator door swung open, startling him. He moved quickly past the operator and stood behind the one other passenger—a stoutish woman with a briefcase very similar to his own—and waited for the door to close again with a sudden look of panic in his eyes.

At any moment now his nerves would start shrieking again. He had to get back to the street and into the subway before his heart began to pound and his temples swelled to bursting, had to bury himself in the anonymity of a crowd that knew nothing about him and—because they didn't know—couldn't turn on him and bare their claws as she had done.

He had to get away before the inward screaming began again.

Chapter III

There was a screaming inside of her and she couldn't seem to breathe. She was being followed. Someone had stepped out of a warehouse doorway and was following her, matching his pace with hers, keeping close on her heels.

She dared not look back, because he was being very careful not to let the distance between them lengthen, even for an instant, and she was afraid of what she might see in his eyes.

Ordinarily she would have become indignant, turned abruptly and faced him, threatened to call a policeman. Then—if he had attempted to grab her, if he had turned ugly—she would have screamed for help.

But now she only wanted to escape as quickly as possible from the terrible ordeal that had made her almost physically ill—twice before leaving her office she had been on the verge of fainting and she'd had to clutch a policeman's arm for support. But the mere thought of facing another policeman, of meeting his cool, arrogant gaze—yes, they were arrogant when they asked you question after question, even though they knew and you knew that not the slightest shadow of suspicion rested upon you—now just the thought of coming face to face with a policeman again was intolerable to her.

Pretending to be sympathetic, understanding, big-brotherly but always the cool, arrogant persistence lurking in the depths of their eyes. She remembered: "I know it's been mighty nerve-shattering for you, Miss Prentiss. A terrible shock. Just to walk into her office, and see her lying there—"

The big, slow-talking one especially, with the beat-up face—a detective lieutenant, he'd said he was. All afternoon until she couldn't endure another moment of it ... the office filled with policemen and photographers and Lathrup not even mercifully covered with a sheet, her dead eyes staring. Not that she'd gone in again to look or would have been permitted inside after the medical examiner had arrived and they'd started dusting the office for fingerprints. But she could picture it, she knew exactly how it was, because Macklin had gone in for a brief moment to discuss something very important with them, and had told her how it was, not sparing her any of the details. (Not his fault! She'd nodded and let him talk on.)

The body stretched out on the floor, with chalk marks on the desk to indicate just how it had been resting when—resting! How mocking, how horrible the image that one word conjured up!

They'd let her go at last, advising her to take a taxi home but to go to a restaurant first and eat something—a sandwich, at least—with two or three cups of black coffee.

Out on the street she'd begun to breathe more freely, had felt the horror receding a little, the strength returning to her limbs. Then, suddenly, terribly, unexpectedly—this!

The footsteps seemed louder than they should have been, even though he was very close behind her and was making no effort to cushion his tread. Each step seemed to strike the pavement with a hollow sound, making her feel for an instant as if she'd become entrapped in a stone vault, and he was walking, not behind, but above her, sending hollow echoes reverberating through—

Her tomb? Dear God, no! She must not allow such thoughts to creep into her mind. Quite possibly she was completely mistaken about him, and he wasn't deliberately following her at all.

It happened often enough. Two people hurrying to catch a train or bus, or headed for the same destination, walking along a street where office buildings had been replaced by warehouses and empty stores, with no other pedestrians in sight and dusk just starting to gather. It was so easy to imagine that you were the victim of calculated pursuit.

She must keep fear at arm's length, Lynn told herself, despite the wild fluttering of her heart, must not give way to panic or hysteria. Otherwise her wrought-up state would warp her judgment and make her do something she'd regret.

The sensible thing to do would be to slow her pace slightly, turn and glance casually back at him, as any woman might do at dusk on a deserted street. It would not indicate that she actually thought that he was following her deliberately or with criminal intent. It would just imply slight bewilderment, a curiosity easy to understand. He wouldn't take offense and it would put an end to all doubt.

But somehow she couldn't even do that! What if she turned and saw that his eyes were fastened upon her as she feared they might be? What if she saw that they were not just the eyes of an annoyer of women, some tormented sex-starved wretch who couldn't resist making an ugly nuisance of himself—what if they were the eyes of a murderer?

What if they were the eyes of a man who had killed once and would not hesitate to kill again—a man with the murder weapon still in his possession, a man who would feel no qualms about putting a bullet in her heart if he suspected that she knew more than she did about Helen Lathrup's murder?

What if he'd found out in some way that she'd been the first to discover what he had done, and that she had been talking to the police, answering their shrewd and persistent questions all afternoon? What if he thought he'd left some damning clue, some tell-tale piece of evidence in Lathrup's office—something which had slipped Lynn's mind completely, but which might come back to her later?

She was quite sure she'd told the police everything. But how could he be expected to know that? Could he afford to let her go on living long enough for some damning memory to come back to her?

He might even be a homicidal maniac. She wasn't a child. She'd read a great many books that dealt with such horrors in a clinical, completely realistic way. One murder was just the beginning; just the igniting spark. They had to kill again and again. The first slaying made them even more dangerous, more insensately brutal and enraged. They weren't satisfied until they had vented their rage on many victims, had waded through a sea of blood.

The mental hospitals were filled with them but you never knew where you'd meet one—on the street, in a bus, sitting next to you in a crowded subway train.

"Lady, I just don't like you. All my life you've been getting in my hair. I've never set eyes on you before, but this time I'm going to wring your neck."

She saw the lighted window of a restaurant out of the corner of her eye and breathed a sigh of relief. She was almost abreast of it, but not quite—there was an empty store she'd have to pass first, as dark as a funeral parlor when the embalmer has turned out all of the lights and gone home for the night. And the footsteps seemed suddenly even closer, as if in another moment she'd be feeling his hot breath on the back of her neck.

She quickened her own steps, almost breaking into a run. She heard him draw in his breath sharply, but she forced herself not to think, to keep her eyes fastened on the lighted pane until she was at the door of the restaurant and pressing against the heavy plate glass with all her strength. The door opened inward—slowly, too slowly—and then she was inside, safe for the moment, with light streaming down and two rough-looking men at the counter and a waitress writing out a check and a big, heavyset man with steel-hard eyes at the cashier's desk who glanced at her quickly and then seemed to lose interest in her.

She wasn't disappointed or irritated or even slightly piqued by his lack of interest—not at all. She wanted to throw her arms around him and say: "Thank you. Thank you for just being here."

She went quickly to a table and sat down, not trusting herself to sit at the counter, unable to control the trembling of her hands. Not just her hands—her shoulders were shaking too, and she would have been embarrassed and ashamed if one of the two men at the counter had turned to her and asked, "What's wrong, lady?" and looked at her the way such men usually do when they see a chance to ingratiate themselves with a young and attractive woman in distress—thinking perhaps that she'd had a little too much to drink and they might stand a chance with her if they went about it in just the right way.

She couldn't parry that sort of thing now—even though it was comparatively harmless if you knew how to look after yourself and there was often a real solicitude mixed up with the amorous, slightly smirking part of it.

She saw him then—saw him for the first time. A tall, very thin young man, not more than twenty-four at the most, hatless and a bit unkempt-looking with burning dark eyes that seemed to dissolve the glass barrier between them as he stared in at her through the window.

Only for an instant—and then he was gone. He moved quickly back from the window and his form became vague, half-swallowed up in the twilight outside. Whether he'd crossed the street or continued on down the street she had no way of knowing. He was simply not there any more.

A sudden tightness gripped her throat and a chill blew up her spine. How completely not there? Would he be waiting for her when she left the restaurant, standing perhaps in the doorway of another building, and falling into step behind her again the instant she passed?

She refused to let herself think about that. There was no real need for her to think about it, for she could phone for a cab from the restaurant—there was a phone booth near the door—and when it came she could dash across the pavement, climb in and tell the driver that she was late for an appointment uptown and would he please ... please ... not waste a second getting started.

But what if he actually was the murderer and still had the gun he'd killed Lathrup with? Why, he could have shot her through the window, could have whipped out the weapon and shot her right through the glass. Or come into the restaurant after her. The cashier, despite his strength and his hardness, would have been powerless to interfere, to protect her in any way. If he even started to come to her aid, he'd be dead himself.

Nothing could save her—if he actually was the murderer and was determined to take her life.

But he hadn't tried to kill her. Not even when he'd had a good chance, outside on the street. Would he be likely to change his mind and try to kill her now?

She stopped trembling abruptly, buoyed up by the thought, as if a great white wave of hope and reassurance had burst all about her, carrying away every vestige of her fear.

A psychopathic killer wouldn't have held back that way. The presence of others would have added fuel to the flames. He'd have realized at once that there were other victims right at hand and would have killed and killed again, in an uncontrollable frenzy, his guilt feelings, his secret desire to be caught and punished, making him welcome the added danger and risk.

And if he was the other kind, the completely sane kind—were murderers ever completely sane?—concerned about saving his own skin, wouldn't he have shot her on the street, the instant he saw that she was heading for the restaurant? Wouldn't he have shot her in front of the darkened store, the store she'd darted past with her heart in her mouth, and not even waited for her to fall to the pavement? Just turning and fleeing, knowing it would take the police minutes to arrive, time enough to put him beyond reach of the law for a few days, perhaps forever. The risk he'd taken in Lathrup's office had been ten times as great.

She was feeling relaxed now, and a little light-headed. Almost all of the fear had left her. It was almost as if the two rough-looking men at the counter had been right about her, as if she'd taken three or four drinks of straight whiskey, the kind that burned your throat—she'd never in her life taken more than two cocktails—and was feeling the effects of it.

He came into the restaurant so quietly, gently pushing the door open and advancing so slowly toward her that for an instant he seemed remote, unreal, like a mist-enveloped figure in a very tenuous, not in the least frightening dream.

Then stark terror whipped through her again. Her hand went to her throat and all of the blood drained from her face.

He was carrying something under his left arm—a black, square something, much flatter than a briefcase, with no handle. But she wasn't looking at what he carried. She was looking at the bulge in his right coat pocket and at the half-inch of white wrist protruding above the pocket, the even whiter shirt-cuff pushed back, the hand itself completely invisible, buried in the pocket, as if the fingers were tightly clasped around whatever it was that made the pocket bulge.

She wanted to scream but couldn't, and when she tried to rise a great heaviness seemed to grow up inside of her, to spread and spread until it enveloped her entire body and turned her into a leaden woman sitting there.

Was the gun that caused the bulge—how could she doubt that it was a gun?—about to go off, or did he merely mean to frighten her?

Surely, she told herself, that was not a sane question. What possible good would it do him to frighten her if he didn't mean to kill her? If the bulge was made by his hand alone did he think that fear alone would bind her to silence? Could he possibly be counting on that?

No, no—it was too wild a hope, too slim a threat to cling to. No man who had killed once would ever show that much restraint, would bother to resort to such trickery. It was not the way of a killer. He would make sure. He could never be certain of her silence otherwise.

She suddenly realized that he was no longer standing. He had sat down opposite her and was speaking to her. His lips moved, but for a moment the words themselves seem to blur and run together.

Then she heard him distinctly. "Miss Prentiss, I don't know just how to say this—how to begin even. I'm afraid you'll think me an impulsive young fool with more nerve than talent...."

He paused an instant to moisten his lips and then went on almost breathlessly, the words coming in a torrent. "You're listed as an associate editor in the two Eaton-Lathrup magazines which use the most interior art work—as a rule, anyway—and the girl at the desk told me you can recommend art work sometimes, even though you don't do any actual buying. I know even assistant editors can do that—put in a strong plug for a drawing. What I'm really trying to say is—you look at most of the work when it first comes in, and when you need a particular kind of illustration for a story you've been editing your recommendation almost always means that the drawing will be bought. It's the same as if you'd made the final decision."

He smiled suddenly—a boyish, not unattractive smile, "I've tried my best to get in to see Miss Lathrup, but they keep telling me she's out for lunch, or in conference or taken the afternoon off or gone away for the week-end. I suppose if I'd been very persistent and made a nuisance of myself she might have consented to see me for a minute or two. But what good would that have done me? What good, really? I could never have persuaded her to spend a half hour looking at my drawings—or even fifteen or twenty minutes. It would have been better than not seeing her at all, but I wasn't counting on it to do me much good."

The smile widened a little. "So I suddenly asked myself—why not? Why not wait until you were through for the day and introduce myself and have a talk with someone with just a little more time, and trust to luck that you wouldn't be offended and that if I showed you some of my work and you liked it you might become interested enough to give me a chance to do at least one illustration on speculation."

Lynn Prentiss sat rigid, her mouth dry, staring at him with such an appalled look in her eyes that he suddenly fell silent, his boyish grin vanishing.

She could not yet fully grasp what he said, could only wait, shocked, paralyzed, for something to happen that would widen her understanding quickly enough for all of the terror to be dispelled. For an awful moment the youth who sat facing her remained what he had been—a sinister and dangerous killer who had no intention of permitting her to leave the restaurant alive. The gun....

She saw his right hand then, the hand she'd imagined firmly clasping a gun, one finger on the trigger ... the gun that would explode in his pocket with a terrible roar, ripping the cloth to shreds and killing her.

He'd removed the hand from his pocket and it was resting on the table now, the stubby fingers still contracted into a fist. A fist ... nothing more! A fist which had been thrust deeply into the coat pocket of a boy keyed up, embarrassed, uncertain of himself—a hard-knuckled fist making, quite naturally, a weapon-like bulge.

She had a sudden, almost uncontrollable impulse to laugh hysterically, to let herself go, not caring what anyone in the restaurant might think, least of all this crazy kid with his sheaf of drawings. It was a portfolio he'd been carrying, she could see that now. The square, black object was a portfolio and it rested on the table; there was nothing but drawings in it, good, bad or indifferent. She had been given back her life and had nothing at all to fear.

"I guess ... I took too much for granted," he stammered. A deep flush had crept up over his cheekbones and he seemed almost on the verge of tears. "You do crazy things at times when you feel that you really can draw, and that just a brief talk with an editor in a position to recommend—"

He gulped and tried again. "I'd never submit a drawing I didn't believe in myself. It took me a long time to learn, and I still turn out bad work at times—some very bad things. But there are a few drawings I'm proud of and not ashamed to show to editors. All I ask is a chance to show one of the really big groups what I can do if the incentive is there, the opportunity ... if I'm given half a chance.

"I suppose that isn't the way an artist should talk ... or even think. He should do his best without giving a thought to the rewards—to commercial success or artistic recognition on a more important level, like getting a picture hung in the Museum of Modern Art. I almost did last year. But even if that happened I could still starve to death."

The impulse to laugh hysterically was gone now, or she found herself able to control it. She wouldn't have been laughing at him, she was sure of that. There was something appealing about him, something honest and forthright—even if brash and almost incredibly naïve—which was beginning to affect her in a strange way. And that was to his credit also, for she was just recovering from the worst scare she'd ever had, the most ghastly fifteen minutes she'd ever lived through.

It was difficult for her to think clearly, to listen with complete sympathy to what he was saying, as she would have done had he talked with her at the office before—

All of the horror came back for an instant and she shut her eyes, seeing the police again, her eyes blinded by the exploding flash bulbs, hearing Macklin's voice, calm, unruffled, but filled with understanding and deep concern.

"I wish you wouldn't be quite so stubborn, Lynn. They'll let you go out right now and get a sandwich and some coffee if you simply remind them that you've had no lunch and it's too great a strain to answer any more questions. I'm having some coffee sent up, but it may not get here for another fifteen or twenty minutes. Just say the word and I'll tell them off and make them like it. That detective lieutenant isn't a bad guy. Naturally he wants to get the nearest thing they have to an eye-witness account down on paper while it's still fresh in your mind. Later, you might forget some important detail. But if you feel bad, it makes sense to say so. You can go out and come back again."

There was a whirling in her mind now, a dizziness that kept her eyelids glued shut for a second or two longer. Why had she been so stubborn, preferring to think of herself as trapped, forced to answer questions while a fierce rebelliousness tugged at her, when she could so easily have followed Macklin's advice and gained at least an hour's respite? With a respite at two, she could have gone on talking until six and perhaps avoided this encounter with another kind of horror—a horror of the dusk that had almost destroyed what remained of her control.

It was gone now, completely. The sinister Jack-the-Ripper figure, cloaked and hugging the shadows, darkly gleaming dagger in hand, had become a blue-eyed, completely harmless young man, as innocent of homicidal malice as a friendly postal clerk or a smiling conductor on a train.

But it was only when she felt convinced that her self-mastery would not falter, that her behavior would be normal and controlled, that she dared to meet the young man's gaze squarely. Even then she found herself trembling slightly and could think of nothing to say.

He had fallen silent, and was staring at her with a kind of pleading desperation in his eyes, as if just a few crumbs of interest had become of almost life-and-death importance to him.

He had to have at least a few crumbs; she could see that. She could sense a stiffening in him already, a refusal to let his pride suffer further indignity. Another moment of silence on her part, and she was quite sure that he'd get to his feet and dash from the restaurant, hurt badly, wounded where he was most vulnerable and not caring what kind of a fool she thought him—except that he would care, later on, and feel bitter about it and think her a supercilious, male-deflating little witch. And she wasn't, she wasn't at all.

She made a supreme effort. "I'm afraid you gave me quite a start just now," she said. "I thought you were following me with the deliberate intention of—well, trying at least to pick me up. Some fairly decent men have been known to do that. But why pretend? What I feared most was that you were the other kind, the sidewalk wolf who makes a habit of annoying women, and won't be put off by a lack of encouragement or harsh words or even a threat to call the police. The ugly kind, the really dangerous kind. And when you looked in at me through the window, when you just stood there for a minute looking in, I got so scared I thought of asking the cashier for protection."

The young man blinked, but said nothing. She frowned and went on quickly: "Why didn't you just walk right up and tell me you had some drawings you wanted me to look at? I wouldn't have been offended in the least. If you'd asked to see me at the office I'd have come out and talked with you. On some of the big magazine groups, editors are hard to see, I'll admit. But that isn't true of all groups and it happens to be our policy to treat writers and artists like visiting royalty. We believe it builds up good will, and we don't worry about whether we'll be wasting advice or guidance on someone who is just learning to draw and hasn't a credit to his name. We're not that conceited or foolish."

She was forcing herself to smile now, doing her best to break down the barrier which her fright had erected between them. "You never know when real talent—great talent, even—will leap right out at you. You didn't get in to see Miss Lathrup simply because—well, she actually is tied up three-fourths of the time. She'd refuse to see the President of the United States if he called at the wrong time."

It was difficult for her to speak of Lathrup as if the slain woman were still sitting before her desk in an interview-considering frame of mind. It was hard to keep the ghastly memory from coming back and overwhelming her again—the terrible look of fear on the sightlessly staring face, the slumped shoulders, the red stain on the floor by the desk. But apparently he knew nothing and breaking the news to him abruptly would have been no help at all in putting him at his ease.

The waitress had snapped her order pad open, and was just starting toward the table to find out why Lynn had failed to catch her eye or indicate with an impatient gesture that she was waiting to be served. Lynn shook her head, and the girl took the cue, scowling slightly and returning to the counter with her eyes trained in curiosity on the table's other occupant.

Having seen him enter the restaurant and sit down uninvited opposite Lynn, she could hardly have failed to think him a pickup artist with a bold way of going after what he wanted, even to taking the risk of being thrown out on his ear.

But it wasn't her problem and she seemed content to watch his progress with mild interest and wait for Lynn to rise from the table in anger and appeal to the cashier for aid. When that didn't happen and the young man straightened his shoulders and a look of elation came into his eyes the waitress' frown was replaced by a knowing smirk and a glance which said as plain as words: "Brother, you sure are a fast-working stud! Funny—I'd never have taken her for a round-heels."

Lynn stared down at the white table-top, picked up a salt shaker and set it down again. She let her gaze stray to the black portfolio and said in an even tone: "We could have discussed your work at the office, and I wouldn't have been in the least bit hasty. You can't just glance briefly at drawings and hope to form a considered artistic judgment. Sometimes you can't even—well, never mind. What I'm trying to say is I think I understand why you preferred to wait until I was through for the day. Office-pressures do interfere—they're a kind of strait jacket. For some people, anyway. I've done things just as—well, impulsive as you just did. Not once, but a dozen times."

He leaned toward her eagerly, all of the uncertainty gone from his gaze. "I sure behaved goofy," he said. "But I'm a shy sort of guy. I try my best to hide it but maybe it would be wiser to just accept it, go along with it. I've been told I'm giving it an importance it doesn't deserve."

"Of course you are," she said. "Some women like shy men. Perhaps sixty percent of them do, when the shyness has something very genuine behind it. Shyness has nothing to do with courage—or lack of it. It's often a blending of humility and strength. And humility is a very fine quality."

"That's the charitable way of looking at it, I guess," he said. "But I'm a great deal harder on myself at times. I started off shy—was that way when I was five—but I could have conquered it if I'd tried hard enough."

The boyish grin was back on his face again. "Sometimes I feel that way, and then again—I don't at all. I ask myself if it isn't a mistake to try to change people too much. There has to be a wide variety of human behavior, doesn't there? That's what makes the world go round. I've always liked something that André Gide once said: 'We are what we are, and we do what we do.' But perhaps you don't agree."

"One doesn't have to be fatalist to agree with that," she said.

His face sobered suddenly. "You should be burned up," he said. "Angry enough to give me a cold stare and refuse to talk to me. About the only thing I can say in my own defense is—I had no idea I'd seriously scared you. I guess that's because no woman has ever before mistaken me for a wolf on the prowl."

"I knew you were walking right behind me and I was afraid to look back," she said. "It was downright silly of me—a surrender to panic that doesn't make sense. I've only myself to blame."

"But why?" he asked, puzzled. "If you'd turned I'd have spoken to you, and introduced myself. I'd have explained that I just wanted to show you a few of my drawings, and if you had the evening free...."

There was a slight curve to his lips again. "I'd have probably gone all the way out on a limb, and asked you to have dinner with me. I was building up to it, just giving myself a second or two more of grace. But then you became frightened and almost broke into a run—"

Should she tell him why, she asked herself? Exactly why she'd been afraid to turn and face his gaze? She decided not to. He'd be sure to think her silence strange, very strange, when he saw tomorrow morning's headlines; but to talk about it now, to watch shock and horror grow in his eyes, was a little more than she could take. Better to let him think that Lathrup was still alive, that she, Lynn, had emerged into the street from a perfectly normal, smoothly functioning magazine office.

Better, safer, wiser to let him suspect nothing. If she ever saw him again—and she had a feeling she would—she could explain why she hadn't come right out and told him about the tragedy. She could count on his complete sympathy and understanding. She was sure of that.

It seemed incredible to her that he hadn't noticed the police activity outside the building, but then she remembered how much that activity had thinned out just in the past hour. On leaving the building she'd seen only two police cars, and one had been parked half-way down the block. News of a murder usually gets around by word-of-mouth and spreads fast, especially in the immediate neighborhood. But apparently he hadn't heard about it, and that was good. It pleased her very much.

Actually, when she thought about it some more, it wasn't in the least surprising. The police tyranny had eased and she'd emerged from the building at five-fifteen, practically her usual hour. In all likelihood he hadn't been waiting for her outside for more than ten minutes, too short a time to become aware of the electric tension in the air, or the morbidly curious stares directed at the building. She was quite sure that only in Macbeth did the very stones cry murder.

She felt a sudden seriousness, a strange kind of heightened tension flowing between them, as if in some way he'd sensed that she was keeping something from him that she didn't want to talk about. To dispel it quickly, for she did not want him to start asking questions she would be compelled to answer evasively, she reached over and picked up the portfolio of drawings.

"Are these the drawings you wanted to show me?" she asked.

"Yes ... please look at them," he said. He seemed unable to restrain his eagerness. It showed in his eyes, which were bright with confidence, and the way he tapped with two fingers on the table-top, with a kind of anticipatory vehemence. It was easy to see that he didn't care how impulsively over-optimistic she thought him, if only she would study each drawing carefully and be completely just.

She opened the portfolio with fingers that trembled a little. Why, why couldn't she keep the hateful memory from unnerving her so when all danger was past, and she would soon be sitting in a taxi, completely safe, completely secure, moving through the crowded streets ... moving up Broadway with its great fountains of colored lights. People everywhere, thousands of people, as alive as she was alive, protected, guarded, shielded from danger by the massive strength of the city, with its law-enforcing agencies constantly on the alert.

She forced herself to examine each drawing with the utmost care, with an eye to color and line and originality of subject matter, putting aside for the moment, and as far as she was able, all of her previous experience in the judging of art work. She tried to think of herself as just an average person roaming at random through an art gallery, stopping here and there to admire a painting with some special quality about it that merited further study and set it a little apart from the paintings on both sides of it.

Then she considered the special qualities in a slightly different way, with a sharpening of critical judgment, summoning to her aid the knowledge and discernment she had acquired as a fiction editor on a magazine group which was always on the lookout for exceptional illustrations and preferred not to leave the discovery and selection of such material to the art department alone.

There were twelve drawings in the portfolio and she spent two or three minutes studying each of them and when she had completed her scrutiny she went back, and made a re-appraisal without saying a word. She was aware of his eyes upon her and an anxiety emanating from him that a word or two might have eased. But somehow she could not meet his gaze or bring herself to gloss over the truth or distort it in any way out of sympathy for him, or simply to spare him pain. He wasn't the kind of young man she could lie to without seriously impairing her own integrity and self-respect. Had she attempted to lie, she was quite sure that he would not have been deceived.

What could she say to him, how soften the blow without cutting him to the quick? Would it do any good at all to tell him the simple truth ... that these drawings had about them a quality of pure enchantment, of greatness, undoubtedly, a delicacy of perception that made her want to weep?

How could she tell him that they were the kind of drawings which no magazine could possibly accept? It wasn't just a question of their being too good. The line between the best commercial art and the canvasses of a Van Gogh wasn't quite that hard and fast. It could be broken down, dissolved away, if a drawing was powerful enough.

But these drawings were too tenuous in a fanciful way, too remote from—well, even the kind of reality that surrealism specialized in—the fragmentary, broken up, subconscious dream imagery that managed to remain sharply delineated, with many bold and contrasting scenic effects ... broken columns against a blood-red sky, an ancient castle crumbling into ruins, a giant's hand clasping an egg. These drawings suggested more a Midsummer Night's Dream seen through the spray of a Watteau fountain in an Alice-in-Wonderland kind of topsy-turvydom.

There were no bold contrasts at all, no clearly-defined human figures, no dramatic, story-telling content. Everything seemed to float and quiver, to be suspended in the air, or to recede into rainbow-hued distances. It was a blue world of enchantment and wonder, bathed in the light that never was on sea or land. But it was not a real world that dealt with the human condition on any level. A sensitive hand had worked with the pigments and hues of Merlin's realm of magic, avoiding the abstract and the symbolical but producing something just as provocatively illusive on an entirely different plane.

She tried to visualize just one of them—the least tenuous, the only one that held the faintest ray of hope—on the cover of a magazine.

No ... no ... absolutely not. The reproduction process alone would destroy whatever vitality the two foreground figures possessed. Didn't he know what the reproduction process could do at times to drawings so sharply delineated that the human figures seemed three-dimensional, right in the room with you?

Five minutes later Lynn Prentiss sat alone in the restaurant, glad that she had told him the complete truth, but unable to forget the look on his face when he'd gotten up and left her. It hadn't been an angry or reproachful look. He had kept a tight grip on his emotions, had even managed to smile and thank her, reaching out and giving her hand a firm squeeze, quite startling under the circumstances and totally unexpected.

He had thanked her for her candor and left, very quietly and with dignity. But behind the smile there had been a look of despair, almost of hopelessness, a shrinking together of his entire being. She could sense it: it was something that couldn't be hidden, that was beyond his power to conceal.

The waitress was staring at her again, her gaze completely mystified now, the cynical smirk erased, as if someone had passed a wet sponge dipped in a muscle-relaxing solvent across her lips. One of the rough-looking men had paid his bill and left, a little ahead of the young man with his sheaf of drawings that would never see publication anywhere unless—

Well, if he got them hung in an important midtown gallery—and it was not beyond the bounds of possibility—one of the art magazines might spend a small fortune to bring them out in just the right way, with the costliest of full-color techniques. The three in color were the best, the cloud formations extraordinary, and she was quite sure that someday the serious critics would sit up and take notice. But recognition might not come to him until he was too old to dream, and meanwhile—he desperately needed to sell a few drawings to bolster up his morale.

He hadn't come right out and told her that he was poor, but she knew he was. He would not have approached her outside the office in such a naïve, reckless way if he had been in any way loaded—she'd always disliked that word, but it came unbidden into her mind. With plenty of money to throw around he'd have acquired more self-confidence, even if serious artistic recognition was something money couldn't always buy. Not immediately anyway, not overnight. But with money and genius—

Was it genius—or merely a very great talent? She couldn't be sure. She didn't know too much about art, but she did know how she felt when she saw a drawing or painting that took her breath away. And the way she felt was important, because she was very sensitive, imaginative and deep in her feelings; she had as much right as anyone to recognize, dwell upon, understand and praise the qualities which made a work of art outstanding.

She had at least praised his drawings; had been unstinting in her praise. And if her absolute candor had seemed almost brutal to him it had been actually something quite different. The truth was never brutal. It only hurt for a moment, hurt terribly, and then there was recovery and healing—you were much better off than you would have been if you'd gone on deceiving yourself. Only deception was bad.... It was the deceivers of the world who were the closest allies of the sadistic ones, pretending to be kind and tactful while inflicting grievous wounds. Not the only criminals by any means—open brutality without any excuse at all was worse—but the kind deceivers were the opposite of admirable.

Or was she deceiving herself a little? Was there something obstinate in her nature which put too great a stress on absolute truth-telling? Well, perhaps. But it was too late for penitence and regrets now. She hadn't slammed a door in his face. She'd told him, quite frankly, to try again. Anyone who could draw that well—could turn out saleable work. She was sure of it. He'd simply have to come down a little more to earth, and put some flesh-and-blood people into his drawings. Heightened drama, direct conflict. Not all the great paintings of the world had that element, but it sure helped when you wanted to sell an illustration to a magazine. Keep things sharp and clear and forget about the beautiful gossamer webbing for awhile. Time enough for that when you're famous and standing with a cocktail glass in your hand on the opening day of your own show.

She found herself visualizing it, sitting very straight and still, aware that the cashier was watching her and not caring at all. Anything ... to keep the memory of the slumped body, the ashen face, the out-thrust arm and ... the blood ... from coming too precipitously back into her mind.

He'd be standing surrounded by his paintings, wonderful elfland vistas, white nymphs in the clasp of satyrs, hairy and dwarfish, with cloven hoofs, and still pools in the deep woods would mirror the background orgies. The women surrounding him would be remarkable too, with plunging neck-lines, ogling eyes, purple-tinted eyelids, incredible gowns, with Cadillacs parked outside, and a guest book bearing the signatures of a hundred celebrities of the art and literary worlds.

His shyness would be gone, but he'd be a little ungainly looking still, a very thin, pale youth with darkly burning eyes.

"So nice ... so glad ... so pleased. Do you really think so? Isn't it strange that we both should know John Tremaine? And Hodgkins. Yes ... I was very pleased by what he said about me in the New York Times. That's right. Some of my early things did appear in the Eaton-Lathrup publications. But I had to ruin them first. Couldn't be helped, though. I take a cynical, detached attitude—"

Suddenly ... fear began to grow in her again, and an icy wind blew up her spine. What if ... he hadn't been quite the naïve, awkward, appealing youth that he had seemed? A few of the drawings....

Morbid? Well, yes ... distinctly on the morbid or suggestively erotic side, with the female forms—creatures of light and air—assuming strange postures as they dwindled and faded into blue distances as if borne on invisible winds. There was nothing repulsive about the figures, they were beautiful with no hint of ugliness or the deliberately perverse about them. But there was a suggestion of amorous abandonment and a strange, smouldering kind of half-virginal, half-wanton sensuality in their attitudes. It was as if the mind which had depicted them could have gone much further in giving them an illicit, orgiastic aspect and had been strongly tempted to do so. What if, in other drawings which had perhaps been shown to no one, all restraint had been thrust aside, and scenes portrayed that would have brought a quick flush to her cheeks—forced her to avert her eyes. She was no prude, but when the erotic aspects of a drawing verged on the pathological, when a completely pagan glorification of sex orgies and unrestraint was accepted as a matter of course it never failed to embarrass her and give her a slight feeling of uneasiness which she was powerless to overcome. Revulsion even, when the candor was too great, and her Puritan heritage too violently assailed.

All her life she had been in revolt against the hypocritical and straight-laced and her Puritan heritage was two generations removed. But there were limits—

It did no good at all for her to tell herself that she was being very foolish and unjust. An impetuous young painter today, determined to be completely true to his inner vision, had every right to be completely candid. There was a wide gulf between powerful and genuine art, executed with complete sincerity and the luridly cheap and sensational which had no artistic merit at all. But it was a feeling she could not entirely overcome.

Always in the back of her mind was the thought: Is he really like his drawings; is that the kind of person he is?

She knew that if such a yardstick were to be rigorously applied two-thirds of the world's great artists and great writers would stand condemned. The erotic was an important aspect of all life—to deny it honest expression was to emasculate art, to do violence to reality in all of its gustier aspects—the kind of reality you found in Swift and Cervantes, Chaucer and Defoe, Goya and Gauguin and Cezanne.

But knowing all that, never doubting it for a moment, why was she trembling again now? Why had something about his drawings, the faint aura of morbidity that seemed to hover over them, made her fearful and suspicious again?

Was it because she had at the beginning imagined that a mad killer might be following her; that morbidity and madness were often closely allied? Was it because she had suddenly begun to realize that deception, too, could be a fine art—if a man were a killer at heart?

He might be everything that he claimed to be, a young, unhappy and frustrated artist, desperately seeking commercial success, and still be a youth with a gun who had allowed his morbidity to drive him over the borderline. A youth with an imagined grievance against Lathrup, compulsively driven to seek redress for that grievance through an act of brutal violence.

When had he called at the office, seeking an interview which had been denied him? Yesterday ... two or three days ago? She had failed to ask him. Not that morning, surely, not before—

But how could she be entirely sure that he hadn't called at the office in the morning, that he hadn't stealthily found his way to Lathrup's office after pretending to leave, and....