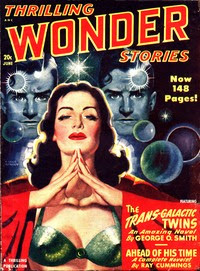

AHEAD OF HIS TIME

a novelet by RAY CUMMINGS

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Thrilling Wonder Stories June 1948.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER I

Radiant Child

He was about two years old when he first became aware that there was always a dim glow of light around him. It was nice, because it shone on the bright-colored little animals, birds and fishes which were on the inside of his white enameled crib. Even in the daytime he was sometimes aware of the glow. In the afternoons, when the summer sunlight was hot and bright, and his mother would put him into his crib when he wasn't a bit sleepy, he would lie staring at the little figures. He could see them plainly, because the pale silver glow was on them.

"But it frightens me, Robert. Our little son—so queer—weird!" That was his mother's murmured voice, as she stood one night with his father at the doorway of his dim bedroom.

"It mustn't frighten you, Mary. After all, you're a scientist too."

Then their voices faded as they went back into their own room.

Robert Thome closed their bedroom door. He was a famous experimental physicist, and his wife was his assistant. Both of them were scientists. Mary Thome knew, of course, that there were things very strange about this little son, but she was a mother as well as a scientist, and she had tried to ignore it, even while it terrorized her. Thome felt that the time had come now when they couldn't ignore it any longer.

"But Robert, that radiance—the way his little body glows in the dark—is like radioactivity."

"It isn't that," Thome said.

A queer opalescent glow kept streaming from the baby's body. When Sanjan was asleep, it could hardly be seen, even in darkness. The glow grew stronger when he was awake. And when he was angry, it sharpened with a new intensity.

"Not some form of radioactivity?" Mary Thome said. "How do you know?"

Her husband gazed at her solemnly. "I even tried the new Watling refinement of the Geiger counter. It showed nothing of radioactivity."

"You've been experimenting on him, Robert?" Mary Thome's voice was shocked.

"Yes," he agreed. "Why not? We can't ignore it, Mary. But there's no reason why it should frighten us."

"Then if it isn't radioactivity, what is it?"

What indeed? Some sort of power. Something inherent to him. Something which of course some day science would be able to explain, but now could only call an enigma.

And there were other things different about Sanjan Thome. Even now, in infancy, his high cheekbones, thin cheeks and pointed chin were apparent. At two years old he was talking with an abnormal fluency. Everything about him was precocious. The look of bright, dancing understanding in his eyes.

There was that time when Robert Thome had held a bright-colored rattle down into the crib. Sanjan had only been a year old then. He had reached for the rattle, but not with a normal baby's slow, uncertain fumbling. Instead, his eyes had flashed; his tiny hand had darted out and grasped it with incredible speed and accuracy.

"All his perceptions are swifter than normal, Mary," Thome had explained. "The messages his brain sends to his muscles are all speeded up."

A gifted child. Why should they think of him in terms of something gruesome? This small human creature was supernormal—superior. The child was a sudden advancement in the slow normal development of the human race. It was as though he had jumped the gap of generations. A human ahead of his time.

Robert Thome no longer felt justified in hiding his secret from his scientific associates. He brought them in. Gravely they studied and tested little Sanjan, who stared at them with his dancing eyes, chattered his grown-up baby talk and was amused and excited by it all.

There was a flurry of comment now, in print and on the radio. Newscasters called little Sanjan a freak, and his mother was appalled and resentful.

"Robert, you're going to ruin his life. You're making him a bug on a pin."

"But Mary, science needs to know. We've something wonderful here."

But public interest died out. The world soon forgets. Science called Sanjan Thome a biological abnormality. To science he symbolized a new eugenics, a product of the New Era of Atomic fission, a mutation. Mary Thome, as a war prisoner in Japan, had been in the outskirts of Hiroshima when the first atomic bomb was dropped.

Seemingly, the radioactivity to which she had been exposed, had wrought no serious effects upon her. But the effects were there. And Robert Thome had been for years one of the key physicists working on the development of atomic fission. He had been in the Manhattan Project, from the beginning, until that first bomb was tested in New Mexico. Then, when the war was over, he had been in Operation Crossroads, meeting Mary about that time, and marrying her. He had always been careful, with Geiger counters to mark when one should no longer expose himself. Or had he sometimes been too eager? Too reckless, in his enthusiasm for this new and wonderful atomic power?

Something had changed within both the mother and father of Sanjan Thome. Science coins names for almost everything, glibly speaking of genes and hormones which are altered by radioactivity, so that they produce something new. What is so mysterious about that? Even the creation of life still is a mystery beyond human ken.

And so Sanjan Thome was a mutant....

Ten years passed, and one day Sanjan was having a quarrel with the little girl next door.

"I didn't!" said Sanjan.

"Yes you did, too! I had only six pieces, you had seven!"

"I didn't!"

"Yes you did, Sanjan Thome. You had seven, and this one is mine!"

But like a darting rapier, Sanjan snatched the last chocolate candy from the little girl and stuffed it into his mouth. She stood startled, it had been so quick.

"Why, you horrid little boy! That's what you are!" She stamped her foot and burst into tears.

"And you're just a cry baby," he taunted. "Besides, I'm not a boy now. I'm a man. I'm ten."

Vana Grant was the little girl next door. She was his only playmate. Her father was the mayor of the town. The Grant garden adjoined that of the Thomes, with only a small hedge between. Long ago, now, Robert Thome had withdrawn his strange child from the world. School was impractical. Sanjan had his own tutors. Peter Grant, Vana's father, was a close friend of the Thomes.

The Grants and Thomes had built a high wall around their two houses and within it was Sanjan's world. Already, he startled his tutors with his ability to learn. At ten, anyone would have called him well educated. Yet mixed with his maturity, there was normal childishness, so that he could play with Vana and quarrel with her.

"I hate you, Sanjan Thome! I hate you, and I'm afraid of you!"

Then as she started to run into her house, he stood stricken.

"Come back, Vana! Don't cry!"

"No, I won't come back! You're a horrid little boy!"

"I'm sorry I took your candy, Vana."

Then he was so immensely relieved when she came back.

That night he said to his father:

"Dad, I took a piece of candy from Vana today. It was hers, but I took it because she couldn't stop me. That's human nature, isn't it? Being greedy. Taking what you can get, because you're stronger?"

"Yes," Thome said gravely. "Yes, it is."

"And if people are that way, of course, nations are that way too," Sanjan said. "They do what I did to Vana. Only when it's nations, it's called war."

Then out of another silence, Sanjan said, "And the atomic bomb makes a nation pretty strong. I can see why every nation wants it."

The atomic bomb—Sanjan, of course, had heard of it all his life. His toys had been built around it and the childish books with which he had learned to read, had told about it. And as he learned more of what it had done in the war that finished just before he was born, the fear of it grew in him.

He said now, "The next war will be pretty awful, won't it, Dad?"

"We hope there won't be any," Thome said solemnly.

Long since, the nations had given up the idea that by some international agreement they could do away with the atomic bomb. There was no way that they could enforce any international laws, save by starting the war they were trying to avoid. So they were making bigger and better bombs, and more of them.

Each day the world hovered upon the brink of monster catastrophe.

CHAPTER II

Impending Catastrophe

A very strange little boy was Sanjan Thome. It was only a few days after his evening talk with his father, that a new aspect of his strangeness was made apparent to him. Fortunately, only to him; and it frightened him at first so that he kept silent about it.

Little Vana saw some of it but, of course, she didn't understand. That afternoon, when she and Sanjan were playing in their garden, one of the village boys climbed the ten-foot wall. His head and shoulders suddenly appeared, and he shouted to some of his companions.

"I see 'im! Here he is, fellas! Sanjan Thome, the freak!"

And the chorus of their voices arose, "Yah! Sanjan the freak! Sanjan the freak!"

Then Vana saw Sanjan's thin, pointed face go pale. His eyes flashed. The glow that was always around him grew stronger, so that Vana could see it, even here in the shadowed daylight of the garden.

"You stop that!" Sanjan called.

"Yah! Freak! Freak!"

"I'm not!"

"You are! Freak! Freak!"

"If I could get out there, I'd show you!"

Little Vana was puzzled, because Sanjan, who had been right here beside her, had vanished. She thought he had run around the house, hoping to get out the front gate. Next she heard Sanjan's voice outside the wall.

"I'm not a freak!"

"Ya are!"

"I'm not! You take that back! I'll—I'll make you take it back!"

The frightened little girl ran upstairs. From the window up there she could see over the wall and saw the fight. The boy was older, bigger and stronger than Sanjan. But Sanjan stood there with his opened hands flicking out. The bigger boy's blows were thrust aside. Sanjan's movements all were so quick, it was like a cat fending off a clumsy dog. And occasionally Sanjan would cuff his antagonist in the face. There was a ring of boys around him, but none of them could touch him. Sanjan taunted them. Suddenly they grew frightened and turned and ran.

Vana hurried downstairs. Sanjan was back in the garden when she got there. He was panting, flushed and laughing, and there was something new and strange about the strange face she had come to know so well.

"You got back quick, Sanjan. Is the front gate open?"

His laugh vanished. He looked a little frightened. "Why—why I don't know. Why, I mean—yes, I guess it is."

"I didn't know you knew how to fight, Sanjan."

"I don't." He grinned. "It just came naturally, I guess. It wasn't hard to keep them from hitting me. Everybody moves so slowly, you know. It takes them a long time to think what they want to do, and then to do it."

They talked of other things. But that evening, Sanjan was silent. This new thing that he had discovered in himself was alarming.

Years passed. One night when Sanjan Thome reached manhood, he leaped from his bed and stood in the middle of his dark bedroom, drawn to his full height. Solemnly he spoke:

"I can't let it go any longer! I've got to stop this coming war now! If I wait even a few days, I may be too late. And I can do it. I have the power!"

There was that strange thing about himself which he had discovered when he was ten years old and had fought the boys beyond the garden wall. Cautiously Sanjan had experimented, careful always that no one should witness it. Through all these years he had said nothing to anyone about it, except Vana. It was their secret. And Vana understood; Vana, wide-eyed and frightened, still was his comfort and his inspiration as he planned what he must some day do.

And now Sanjan, the man, stood in his bedroom, telling himself:

"No one in the world could stop this war now, but me. Since I can do it, surely, I must try."

Because war at last was at hand! Absolutely inevitable now; and only this afternoon Sanjan had learned of it. The thing still was secret from the world public. But Peter Grant had been to Washington, and had returned today. At once he and Robert Thome had conferred and Sanjan had overheard them. Definite ultimatums had been sent. A dozen nations were mobilizing because it was obvious that the ultimatums would be rejected. Someone would strike, with atomic bombs.

There was a mirror on the wall of Sanjan's bedroom. The glow of the faint streaming opalescence from his pajamaed body showed him his reflection—his tall, slim, muscular figure, with his strange high-cheek-boned face shaded by his crisp, unruly blond hair.

He would need the proper clothes and a few simple accessories for his task. He had told Vana that, as they sat out in the garden just the other day, and Vana had promised to get him the things at once, from some other town where she was not known. She would leave them under the porch of her house. Perhaps she had them there now.

It was a comfort, telling Vana his plans. He had told Vana that he had to make the try, and almost tearfully she had agreed with him.

"You can see, Vana, that I must avert this war, to avert the deaths, the maiming of millions. I can do that—hold it off for my lifetime."

"By then," Vana said, "conditions may have changed. Another war may never start brewing."

Sanjan laughed. "You're a dreamer, Vana. Nothing can change human nature."

"This may," she said. "This strange thing you hope to do."

His smile faded. "Everything about me is so strange, Vana. It is, isn't it? And yet I feel perfectly normal."

"Sanjan, you are not strange, not to me."

"I love you, Vana. I think I have always loved you."

She was grown now—eighteen years old. She was tall and dark. She smiled at him.

"I used to be afraid of you, Sanjan, when I was a little girl."

He smiled. "But not now?"

"No, not now. Because I know now that you are one man in all the world that nobody should be afraid of."

"Some should," he said. "Some will." His luminous eyes flashed. "Believe me, some will, Vana...."

In his bedroom now, Sanjan drew a bathrobe over his pajamas. It was midnight. He and his father were alone in the house, for Sanjan's mother was dead now. His father perhaps might still be working in his little experimental laboratory downstairs. Sanjan descended the steps and entered the workroom.

"Oh, it's you, Sanjan. I thought you'd gone to sleep."

"No, Dad, I want to talk to you."

"Why, of course, son. What is it?"

The glow of the fluorescent tubes on the big littered table laid its eerie sheen on the thin figure of Sanjan's father. He was a man of nearly sixty now, with twenty-five years or more of this atomic fission work behind him.

"You look very tired, Dad," Sanjan said.

Thome was haggard. His face was drawn. He smiled in a tired way.

"Yes," he agreed. "I suppose I am tired. Just a little thing here is baffling me and I've got to solve it. So much depends on my experiments."

"Yes Dad, I can imagine," Sanjan said. There was a bond of love between these two.

"I've got to put it over," Thome repeated. "The laboratories in Washington—the whole resources of the Bureau of Standards, will develop my findings. I've got to do it tonight."

"I understand," Sanjan said. "The urgency—Mr. Grant came back from Washington this afternoon, didn't he?"

"Yes, he did. And—"

"You needn't tell me, Dad," Sanjan interrupted. "War is coming. Positively. No chance of avoiding it now, is there, Dad?"

"No," Thome said. "No chance now. And so I've got to finish this job here. I've got to finish it tonight."

Robert looked weary, almost ineffectual, with the tubelight on him and the paraphernalia of his science around him. He was just a tired old man trying his best to cope with the maelstrom of whirling world events. It made Sanjan, with his youth and strength and the knowledge of his power, feel an added urge that he must end this sort of thing in the world.

"Dad, don't think I'm talking wild," Sanjan said. "Dad, listen, there's a chance that I can stop this war."

"Stop the war?"

"Yes. Never let it start. Make it impossible. I think I can do it, Dad."

Thome could only stare at his strange young son. Sanjan plunged on.

"I'm going to try and destroy the war plants and materials of war all over the world."

"Sanjan!"

"Or at least, what I can't destroy, I can make ineffective, useless."

"Sanjan, what do you mean? Such talk is preposterous."

"I can do it, Dad. I really think so. Alone. Just me, alone. Naturally, it would have to be me. There is no one else."

Puzzled, and with a sudden apprehension on his thin drawn face, Thome mutely stared. He had so often heard Sanjan say strange things, but nothing like this. Then Thome murmured,

"You say you can do a thing that's impossible, Sanjan? How? How could you do it?"

"I'd rather not tell you, Dad," Sanjan said gently. "At least not now. It would only worry you. And I imagine you'll say I'll never be able to accomplish such a task, even with the power I have."

"Power? Power, Sanjan?"

"Yes, Dad. Something about me which I've never told you. In fact, I've hidden it from you." Sanjan jumped from his seat and put his hand on his father's shoulder. "I don't want to tell you now. I don't want you to try and dissuade me. I love you very much, Dad. I respect you, but I'm going to try this. I may be killed. I don't know. I'm going away."

"Away?" Thome echoed. "What do you mean away?"

"I wouldn't have told you at all, but I didn't want to worry you, when you found I wasn't here. I'm going tonight."

"Going where?" Thome demanded. "Sanjan, you know that's not practical. We've agreed that's it's best for you to stay here in just this house and the grounds. I know it's been a horrible handicap, son, but—"

"I'm going, Dad. But I'll come back. And if there are people killed—please, you'll understand I'll avoid that as much as I can."

There was real terror on Thome's face now. Had a madness descended on his strange son? Some new development in the supernormal mental and physical makeup which was Sanjan?

"People killed?" Thome ejaculated. "What do you mean by that?"

"I'll avoid it when I can, Dad. Please, please don't be so frightened!"

"You—you plan to be a murderer, Sanjan? Why, I never heard you talk like this before."

"If I could stop the war, that would prevent mass murder on a scale unthinkable," Sanjan retorted. "And to do that some persons must die."

"Sanjan, please," his father interjected, "don't let's talk about it now. Tomorrow, yes. We'll discuss it tomorrow, son."

"Tomorrow I'll be gone. But I agree there's no sense of us discussing it."

"Just go up to your room, and go to sleep," Thome said soothingly. "You're all wrought up, and I don't blame you, of course. So am I. Tomorrow we'll—anyway, you'll go up to your room now, won't you?"

"Yes," Sanjan said. "And by tomorrow, you'll begin to understand. And don't be frightened. I'll take care of myself—and I know I'm acting for the best. Good night, Dad."

He almost had said good-by, but he choked it back. He stood in the doorway of the little laboratory, smiling gently. "Good night, Dad," he repeated.

"Good night son," Thome stammered. "I'll call you in the morning."

Then Sanjan closed the door and was gone. For a moment Thome sat numbed, with terror rising in him. Then on impulse he went out the little side door of the laboratory, across the moonlit garden and into Grant's house. At least it would comfort him to unburden himself to his friend.

CHAPTER III

Sanjan's Mission

Peter Grant was alone in his ground floor study, poring over papers which he had brought with him from Washington. He was a squarely built, stolid man of fifty. Essentially practical.

"Well, hello, Robert," he said. "How are the experiments coming along? Have a drink old man. You look all in."

"It's about Sanjan," Thome said. And then he poured it out to his friend—Sanjan, suddenly mentally deranged? Peter Grant agreed silently, though he would not say so to his friend.

"What am I going to do?" Thome asked him.

"He says he's going away," Grant said. "I think you ought to put him under good medical care.

"Lock him up?" Thome emitted a gasp. "My son—incarcerated? No! No!"

"Well, not just that, Robert. Don't call it that. Just—take closer care of him, until we find out what this means?"

"No! No! I'll take care of him—I always have!"

"He says he'll be gone," Grant responded practically. He hesitated, and then he added, "You forget. I'm the mayor here, Robert. Silly little job, but I'm it, just the same. And there's a responsibility. By the way Sanjan talked of destroying property and killing people, if it had any meaning at all—well, you could call him a menace to society. You could, couldn't you?"

Grant didn't press the point. He soothed his friend, and presently Thome went back to his laboratory.

But as soon as he was gone, Peter Grant called the police....

Sanjan didn't see his father go into the Grant home. From the laboratory, Sanjan went to his room, stayed there a few minutes, and then he went to where he found the things Vana had left for him under the porch.

Back in his room, he dressed himself—heavy lumberman's boots, heavy stockings, thick dark trousers, shirt, and a warm jacket. There was a wide leather belt around his slim waist—a belt on which he could hang a small, sharp hatchet, a knife, an iron mallet. Such simple things, in the great modern world of weapons. But he could think of nothing else that really would be useful to him....

He was surveying himself in the mirror, when suddenly there was a knock on his door—a knock imperative, followed at once by pounding.

"Come in," he said. "That you, Dad?"

He had forgotten that the door had a spring lock, which fastened it when he had banged it closed. He opened it now. Then he stepped back, drawn up against the wall as the men streamed into the room, bulky men in uniform, the police!

"Sanjan! Sanjan, lad, I didn't do this! Believe me, I didn't!"

That was his father, standing by the doorway, gray-faced, terrified and shaking.

Sanjan's alert gaze flicked to Peter Grant who moved into view. Grant was tense, nervous, trying to smile. "I did it," said Grant. "I sent for the police, Sanjan. Just for your own good, my boy. You know I've always been your friend."

"Of course," Sanjan said. "I don't blame you, Mr. Grant."

"We're detaining you for your own good, Sanjan, until we understand what you've got in mind. Now don't get excited."

"I'm not excited," Sanjan said. He stood backed against the wall, regarding the line of men before him. The Law! They had come for this menace to society. But they were still undecided. The leader, a police inspector, turned to Robert Thome.

"Tell him not to make any trouble, Mr. Thome."

"They won't hurt you," Sanjan's father said.

"No," Sanjan said. "I know that, Dad." There was an ironic smile on his lips, but no one noticed it.

"You're not being arrested," his father said. "They just want you to go with them to a comfortable place that's better than this. I'll come there in the morning, Sanjan."

"I understand, Dad, of course."

"Go quietly with them," Peter Grant said, "We don't mean it as any indignity, Sanjan."

"I understand, Mr. Grant."

But he did not move. The men started forward, with a great show of braveness because they were the Law—and the Law must be obeyed. Sanjan's lip curled.

"I am not going with you," he said to the police inspector.

One of the policemen let out a rough, jibing oath.

"Good-by, Dad," Sanjan said suddenly. "Try not to be worried over me."

Sanjan put his thoughts on the Great Smoky Mountains and that war plant there in Tennessee. Sanjan knew that there was a huge laboratory there. The finished atomic bombs were not assembled in the war plant; merely the basic materials, and the intricate parts of the firing mechanisms. There would be no atomic bomb explosion. He did not want that, here in America.

But it would be a good place to start. When suddenly the Great Smoky Mountain plant, so famous, was wrecked, it would shock all the world.

Thoughts are instant things. As the policemen rushed at Sanjan, and his father was pleading in terror, Sanjan's intense thoughts of the Great Smoky Mountains seemed to bring them before him like a threshold opening up. They were a wide, dim threshold in a great gray void where things were surging, fleeting things taking form, evanescent as thoughts themselves.

There was an instant, briefer than anyone might mathematically name, and during it Sanjan knew that he was thrusting himself forward, so that his bedroom and the uniformed men and his father were dimming into a memory and he himself was a part of the evanescent things which were growing plainer.

The Great Smoky Mountains formed themselves into solid, serrated ranks of dim purple, rising up against the distant starry sky.

Sanjan could feel his feet standing on rocky ground. Moonlight was falling on the little rocky declivity here, where stunted mountain trees were growing. Smoke curled from the chimneys of a rambling group of wooden buildings down in the valley which, he knew, were the big laboratories and the factories where the parts of the firing mechanisms of the atomic bomb were being made. Though it was midnight, the place was humming with activity. Naturally this would be so, in this world crisis!

Sanjan smiled grimly as he gazed at the plant. How pleased the leaders of the enemy nations would be when they got the news that the Great Smoky Mountain Plant was wrecked! But their pleasure wouldn't last more than an hour or two—he could promise them that!

A little cave mouth opened beside Sanjan. He turned and went back into the darkness of the grotto and sat down on a rock. He would sit here for a while, planning, and then go into action....

Back in the Thome residence the sudden disappearance of Sanjan had brought consternation and amazement to the police, Sanjan's father and Mr. Grant.

"My gawsh, he was right there!" yelled the inspector. "He may be hiding behind some of the furniture. Search the room." But a hasty hunt failed to disclose Sanjan and, at last, the police were forced to conclude that in some way he had escaped.

Another policeman, not trying to invest the vanishment with science, explained it neatly. "He was right there, and then he wasn't!"

Despite Robert Thome's care, news of it soon got out. Even while Sanjan was still sitting in the cave in Tennessee, the news of what had happened in the quiet suburban home of Robert Thome, the physicist, was ringing around the world, by press, the radio, the television.

"Sanjan Thome, the mutant, son of Robert Thome, demonstrates his supernatural power!" went out the word. "Supernatural monster threatens wholesale murder!"

For that moment the great world of modern civilization, busy and tense as it stood on the brink of war, paused momentarily in its billion billion war-making activities, to contemplate this new sensation. At first everyone believed it was a hoax, but the myriad channels of the news very soon convinced them that it wasn't.

Supernatural! Even the word itself inspires a thrill of instinctive fear. The Unknown! No one can face it without a surge of emotion. Even now, just at the beginning of Sanjan's activities, the very thought of him was inspiring terror—a terror which was to prove his greatest asset.

The Unknown. Already Science was explaining it.

"Sanjan's power, miraculous as it seems, of course can be explained scientifically." That was the verdict of a learned scientist, who for a big fee had been summoned to a broadcasting studio in such a rush that he had to plan his talk enroute. "The strangeness of it is only that we have not witnessed it before."

Within half an hour, other savants were expounding a theory. One could listen and think surely that he understood the learned phrases, which cited the fundamental instability of all matter, that in last analysis can be reduced merely to motion. Why, Professor Eddington said just that, way back in 1910! Thus, motion is the basis of Matter. And matter has only a seeming solidity, like the whirling of propellor blades. When in motion, the blades seem like a solid disc. They feel like it, if you put a hand against them. And motion Itself, which creates matter, is the motion of what? Eddington had the answer to that! It is motion which is just a maelstrom of nothingness!

And so many others have spoken and written of a latent power—something which might be within one's self—a power with a vibration so infinitely rapid, so infinitely tiny, that it could be compared only to the vibrations of thought. And yet, it was something different. It consisted of a power which could disassemble all those basic whirlpools which make up the human body, and hurl them elsewhere in that same instant with the speed of light, to reassemble them.

And the learned scientists, with their minds on the big fees and their personal prestige, mentioned the Quantum Theory.

"There is no continuity of existence of anything material. For an infinitesimal instant it exists, instantly is blotted out, re-existing again an infinitesimal instant later. And each time it is not what it was before. Each time it is changed. Just a little—but changed both in itself and in the different part of space which it occupies."

And this monster Sanjan—what was he?

Whatever he was, certainly he was not miraculous.

The actual, factual news, during this first half hour while Sanjan himself was sitting quietly in the darkness of the little Tennessee grotto, could only explain that the weird mutant son of Robert Thome had vanished in a glow of radiance. But the terrified Thome felt now that he must tell all he knew, so he explained what Sanjan had said to him. And Peter Grant joined him in the telling. Sanjan had vanished, but he would reappear somewhere else. And his plans were sensational!

The channels of news were babbling garbled versions. Leaders of nations everywhere in the world, some of them roused from sleep, went into hasty, startled conferences. This fiend was going to strike at their war plants! The guards must be redoubled! But that was futile. This was a thing supernatural. Or was it just a hoax?

Already, in a way he had never envisaged, events were helping Sanjan. For a little time at least the war plans of the world were being neglected!

And then, in the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee, Sanjan struck his first blow.

CHAPTER IV

Master of Destruction

The cave mouth behind him was a dark, yawning little pit but the path down the declivity was white with shining moonlight. Sanjan had left his heavy, fleece-lined jacket in the cave as the night was warm and the jacket would only impede him.

He started down the path. It would be a long climb down into the valley, where the buildings showed as a cluster of lights and the moonlight glistening on the roofs of the low, squat buildings. It appeared to be a long climb down, but he suddenly smiled. For him, it need only be a flash of thought. The laboratory building would be the best place to start.

In that moment as he stood there in the moonlight of the path, Sanjan did not see the blob of a man's figure, below him, on a crossing path. The blob was in the inky shadow of a big pine tree. Though Sanjan, of course, could not know it, the blob was Officer Jonathan McGuffy, of the local police. McGuffy had finished his long day's work and was on his way home. Down in the nearby village he had heard the startling news with which the world was ringing.

Then, quite suddenly, he saw a figure on the other path above him, plain in the moonlight. It was Sanjan, the supernatural fiend! McGuffy had heard the radio descriptions of how Sanjan looked, how he was dressed. He was sure the figure above him was the mutant human who had tonight startled the world.

McGuffy's revolver seemed to leap into his hand. He leveled it. In McGuffy's moment of gasping shock, he didn't stop to think that he might be wrong—that this might be merely some stalwart young mountaineer of the region. Nor did it occur to him that, so far, Sanjan, the superhuman fiend, actually had done nothing for which he deserved death. McGuffy was only thinking how wonderful it would be if Jonathan McGuffy could spring into world fame, right now, by killing the monster.

He steadied himself, bracing his arm against the tree. He took careful aim. He was a crack shot. Though Sanjan did not know it, that was his first moment of supreme peril. His body was only human. A bullet would kill him. He was thinking of the interior of the big laboratory down in the valley. A gray threshold was opening before him.

McGuffy's finger did not pull the trigger. He gasped. There was nothing up there in the moonlight of the other path, nothing but the faintest tinge of opalescent radiance, mingling with the moonlight where the figure of Sanjan had been.

If McGuffy had had even the faintest doubt that he had seen Sanjan the fiend, it was dispelled now. For a moment he stood transfixed with disappointment. What an opportunity! Cautiously he picked his way up to where the figure had been. Then he saw the cave mouth and, exploring the little grotto, he came upon Sanjan's jacket. The inference was obvious. Sanjan expected to return here.

If McGuffy had done what perhaps he should have done, he would have notified his superiors at once of what he had seen here. But he didn't. He was picturing himself, alone and unaided, killing this monster, and delivering Sanjan's body in triumph. By tomorrow, everyone in the world would have heard of Jonathan McGuffy. At the very least, he would get on the Nashville force. He'd be Captain McGuffy!

So McGuffy stayed where he was. In a corner of the cave he crouched, with drawn revolver. He was alert, watchful. But inside he was shuddering....

The big interior of the Great Smoky mountain atomic laboratory was a blurred scene of eerie lights and a litter of apparatus in the midst of which the figures of the workmen moved with silent efficiency. Suddenly one of them looked up, pointed toward a doorway and yelled:

"Look! Who's that?"

In the dim glow of his opalescence, weirdly apparent here, Sanjan was standing motionless, as he looked around. In the corridor behind him, he could hear the outer guards calmly talking with each other.

"What you want?" one of the workmen called. They had been so busy here, during this last hour, that they hadn't heard about Sanjan. But at this first quick glance they saw nothing weird about him.

They all stood staring now at the intruder, a hundred or more of them. "Who the devil are you?" somebody called. "No one's allowed in here!"

"You must all leave," Sanjan said. "You'll be killed if you stay." Then behind him, he could hear the alarmed guards coming on the run. They were shouting.

"Hey! What's goin' on in there?"

One of them fired a warning shot. It whistled over Sanjan's head, thudded into the ceiling above him. It startled him. Never must he forget that he was human!

Then the workmen in the laboratory were gasping, numbed, suddenly mute with incredulous astonishment. The figure of the young man intruder clad in heavy high boots, broad leather belt and heavy dark shirt, had suddenly vanished from the doorway! Only the glow of him was there. But almost instantly they saw him again at the other side of the room.

"Run!" Sanjan shouted. "Get out of here! You'll be killed, I tell you!" With a sweep of his arm he smashed a line of glowing retorts.

Incredible saboteur! Suddenly it was as though the room were full of duplicating mirrors, each of them in succession holding a fleeting image of the appearing and vanishing Sanjan. As though a dozen of him were present on the little iron balcony; over there in the corner, smashing with a mallet the controls of the electric furnace.

In the panic of the room, the running inmates met the oncoming guards, forced them back. One of the guards had heard the news over the radio.

"It's Sanjan the fiend!" he shouted. "Run! Run for your lives! It's the fiend!"

Then Sanjan knew he was alone, with acrid fumes and smoke rising around him. For just another moment he stayed, with his iron mallet crashing at the wires and tubes. The deranged electricity crackled, sparkled with showers of colored sparks. And the derangement spread. Short-circuits followed, and explosions of chemicals from retorts which had crashed. A hissing, crackling, spluttering turmoil in the midst of which flames were rising, spreading, attacking the interior woodwork of the room....

On the path by the cave, Sanjan stood gazing down into the moon drenched valley. Smoke and flame were down there—flame mingled with the constant bursts of explosions. All the buildings were aflame now. A great burst of fire gushed up as one of the roofs fell in, the blurred, reverberating roar of an explosion coming a moment later. A yellow-red glare spouted heavenward with billows of smoke rolling up.

For a moment the panting Sanjan stood on the path, gazing down. He was tired, winded. One of his hands was burned a little. He would lie in the cave for a while, and then—the Ural Mountains war project perhaps should be next.

He found himself in the cave. He had left his jacket here. Where was it? By the glow of opalescence from his body he could see that the jacket wasn't where he had thought he left it. Then he saw it, lying on a nearby rock.

Some tiny sound, instantly apparent to Sanjan's swift, acute senses, gave him a flash of warning. Across the cave he saw the blob of a dark crouching figure with a revolver leveled at him!

In that flash, when he became aware that he was being attacked, Sanjan could have escaped. Thought of that munitions plant in the Ural Mountains again came to him, but he thrust it away. He must not always vanish when attacked, like a craven coward. To the world then he would be just a fugitive, to be hunted and assailed with impunity. This was his chance to show his prowess.

Officer McGuffy's revolver spat yellow-red flame. The bullet sang through the radiant space where Sanjan had been. McGuffy gasped as Sanjan loomed beside him. Perhaps in a normal fight the burly McGuffy would have given a good account of himself. But he was too dazed and terrified now. With a blow of cat-like swiftness Sanjan knocked the weapon from his hand.

"You're not quick enough," Sanjan said. "Come on! Can't you fight?"

McGuffy did. Or at least, in his desperate terror he tried to strike back at this weird, glowing adversary. He straightened, staggered, and then Sanjan was cuffing him, nimbly avoiding the bigger man's bull-like rushes. With doubled fist he struck McGuffy in the face, parried what to Sanjan was a slow, clumsy swing, and hit his assailant again. McGuffy went down. Sanjan bent over him. Sanjan's knife point was at McGuffy's throat.

"Don't—don't kill me!" McGuffy gasped.

"I'm not going to kill you," Sanjan said. "But you realize that I can, very easily. You go back and tell them that. If you don't, I'll seek you out and kill you next time. You tell them, whoever attacks Sanjan will die! You understand me?"

"Yes—yes—I will!" McGuffy yelled.

In the next instant he knew that he was alone in the cave, with only a brief faintly lingering radiance to mark where his weird antagonist had been.

To inspire terror, Sanjan knew that was his greatest single asset, and he knew he needed it. Already he was beginning to realize the monumental size of the task before him. And the little incident in the Tennessee cave with McGuffy immediately was helpful. Sanjan found an unoccupied house in the dark, nearby village. He found a radio in its living room, turned it on, and for a moment listened.

"The Great Smoky Mountain Laboratories and factories have been destroyed by Sanjan, the supernatural monster!" an announcer was crying. "The Tennessee war plant is in flames and almost total destruction has been reported, with a death toll of thirty-three."

Sanjan listened grimly. He had done his best to minimize those deaths. There would be more, of course. Soon Officer McGuffy was mentioned.

"—and in a nearby cave, Officer Jonathan McGuffy of Pine Ridge, met the fiend in personal encounter.... He's an unkillable monster...."

The dazed and terrified McGuffy had garbled it considerably. Sanjan chuckled grimly as he listened. McGuffy was convinced that his bullet had gone through the fiend, and had not harmed him, that Sanjan was an unkillable being, in the guise of a young man, wholly supernatural! It was what Sanjan had hoped. Surely the McGuffy incident would inspire a new terror which would be helpful.

The warplant in the Ural Mountains now required his presence.

Sanjan a moment later stood on a rocky height of snow-clad peaks, gazing down at the huddled group of buildings in the hollow, with their lights and electrified fences and alert guards. Fighter planes droned overhead. This plant would be more difficult. He needed to know just what was inside, just where the munitions were located, and to determine how he could cause an explosion.

Soon he stood in a corridor, listening at a doorway to the men who were talking inside.

He investigated one building, then another. He had not been seen, not as yet. There was no alarm....

An hour had passed perhaps, since he had sought refuge in the unoccupied little house in the Tennessee village and listened to the radio. He knew now, here in the Ural Mountains, how when the proper time came, he could inspire panic by making his presence known, leaping with a flash of thought from one part of the buildings to another so that the panic-stricken workers would flee. Afterward he would set off a bomb which would detonate all the explosives here.

His was a strange power—so gigantic in its practical workings, and yet so queerly limited. In these few hours he was hungry, thirsty, tired. His muscles ached. These were simple human needs which had to be supplied, and he was just one person, with the whole gigantic world teeming with the activities of war.

For that moment as he thought of it, Sanjan was appalled. There were warships on the high seas. Just for a moment now, he sought one of them out. In its engine room he appeared, shouting,

"I am Sanjan! I have come to sink this ship!"

On the bridge he stood beside the Captain. "I am Sanjan! I order you to abandon ship!"

Like a will-o'-the-wisp, appearing only for seconds in a myriad parts of the huge vessel, until at last it lay wallowing in the seas, abandoned. This task had only taken a few minutes, but the ship was just one of so many!

Sanjan saw now that he must bring other factors than mere sabotage to aid him in stopping this war. There must be intimidation of the world's leaders. The Ural Mountain plant still was unharmed. The Tennessee plant was destroyed. From what the world knew, so far, this monster Sanjan was only attacking America. Sanjan realized that this was the strategic moment for him to appear in Washington. He stood on the bridge of the abandoned warship wallowing in the seas off Cape Hatteras, and thought of what he must do, in Washington....

The President and his cabinet were in a midnight emergency session. The Secret Service men were watchful outside their closed doors. Then the grave-faced leaders of the greatest government in the world looked up from around their big polished mahogany table and they were terrified, mute with dazed incredulity as they stared at the glowing intruder in their midst.

"The fiend!" someone gasped. "Sanjan is here!"

"Sanjan, the mutant," Sanjan said. "Don't cry out. Quiet now! You can see that I can kill any one of you. But I won't. I've just come to warn you."

One of the cabinet officers recovered his wits a little. "Sanjan Thome," he said. "You're an American—and you turn your power against us! You are using your diabolic power against your own country."

"It would be too bad if I stuck to that policy, wouldn't it?" Sanjan said. "Our enemies, just for this moment now—well, I guess they're gloating. You and your allied governments sent them an ultimatum. Today."

"It had to be sent," the cabinet member explained. "Don't you understand—"

"I tell you now to withdraw it," Sanjan said. "Make that public now. It will give me time. You'll do that because you know that I can come back at any time and kill any one of you. How can your guards protect you?" His eyes flashed and every man in the room knew that he meant what he said. "I can kill you—at your desks—in your bedrooms!"

CHAPTER V

World In Terror

Within an hour the world's radios were blaring the news.

"At an emergency press session, the President at three a. m. this morning, announced that the ultimatums sent today have been temporarily cancelled. The Ambassadors involved have been instructed immediately to cable their governments."

And there was another conference taking place, high up in an Alpine retreat. Sanjan quietly listened to it; learned what he wanted to know. Then he appeared and warned the officials as frightened interpreters there mumbled a translation of his words:

"The ultimatums from America and other nations have been withdrawn. You can save face with your people now and you have no need to cross that border. Your armies are mobilized, ready to sweep forward. I know that. Order them back! If they're on the march now, order them back!"

He made a sudden movement toward one of the dazed, uniformed men—a man gaudy with the military decorations, a leader of great importance to his hypnotized people.

"You!" Sanjan said menacingly. "It would give me great pleasure to come back and stick a knife into you!"

Radiance quivered where he had been, and then he was gone....

With the quickness of thought, Sanjan returned to the Ural Mountains to carry out his plans there. Within twenty minutes a powerful radio was announcing to the startled world:

"The great Ural Mountains plant has just been destroyed by an explosion. Sanjan, the monster, has made his appearance in Europe."

In England and America great multiple presses started to roll, rushing out special editions of newspapers. Excitement mounted throughout the world.

But the inflammatory ultimatums had been withdrawn and in mid-Europe, the massed armies did not move. A week passed. Then another. The world had been upon the brink of war, but there had been a change, a halting change, perhaps merely temporary. Every leader, as he went to bed, could not help thinking:

"Will the supernatural monster come here and try to kill me? Our war plants are being destroyed. Without our weapons of war, we will be defenceless against the enemy. Sanjan must be trapped!"

For days and weeks now, the prospects of war had taken secondary place. The outraged, frightened world was hunting for Sanjan. News of him continued to pour in.

"The monster has been seen at the Greenland International Airbase." Then: "The fiend appeared last night on a hill in Malta. Subsequently, several vessels of the Mediterranean fleet were wrecked."

There were times, when in any secluded place he could locate, Sanjan had to sleep, always with the danger that he might have been seen and might be killed while sleeping. Many times, at night, when hungry and thirsty, he skulked along the roads and among the houses of villages, seizing what he needed.

Like a fugitive, with the world hunting him, was Sanjan! It was the world's most hated and feared name. But, day by day, night after night, the destruction went steadily on.

"Singapore Naval Base has been severely damaged.... The Smolensk atomic bomb plant has been wrecked.... The Alaskan airbase has been attacked by the monster!... Great atomic bomb plant explodes in Chile, and the area of dangerous radioactivity spreads. Santiago has been evacuated! South America, last night, received its first visitation by the supernatural monster. Panic is spreading in the capitals of the southern Republics. Conference in Buenos Aires forms new plans for hunting down this menace to the world."

How could there be time for nations to be making war on each other? There was only the cry:

"Sanjan must be destroyed!"

At the conference in Buenos Aires, Sanjan for a little time stood ironically smiling and listening, listening behind portieres. Spanish was one of the languages he had readily absorbed from his tutors when he was a child.

He listened to the futile plans which were being made here to trap him. Then, for just a few seconds, he appeared in a distant, open corner of the room and told them in Spanish:

"You fool yourselves. I cannot be caught. I cannot be killed."

Quickly he was gone, with only his radiance lingering after him....

A few days later, the Head of the Federal Bureau of Investigations, in Washington, was conferring with the President, the cabinet members, congressional leaders and police commissioners from the leading cities of the nation.

"Every effort must be made," the President was saying. "We must try and persuade him to turn his activities only against our enemies."

They discussed it.

"But he couldn't be trusted," the F.B.I. head said. "That's obvious. He is deranged mentally." Sanjan departed.

The leaders in the Alpine retreat were, almost at that same time, saying the same things.

"He is deranged. He must be killed."

The listening Sanjan smiled and Sanjan appeared among them. He was blazing with anger. He could speak enough of their language to rip out:

"While I live, you will never resume your plans. I shall stop destroying property soon, and destroy only the world's leaders!"

His grim words were still echoing in the room after he was gone.

At long last his thoughts had turned homeward, for a great nostalgia had overcome him. In a few seconds he was there again, back in the garden where he had spent his youth. He concealed himself behind some bushes and slept soundly for a time. Then he sought out Vana Grant and told her all that he had done. She knew most of it from the radio and the newspapers, but she heard it all over again, from his lips.

That afternoon they spent in the Grant garden, hidden safely by the trees and shrubbery. Here they could not be seen or heard from the houses, if they talked softly. Finally she threw her arms around him and gazed fondly into his face.

"You are so changed, Sanjan!" she said.

His boots were worn, his clothes ripped and soiled, burned in places. There was a growth of ragged beard on his face and he was haggard and drawn.

"I wanted to see you, Vana," he told her. "Just to be near you, for a little while."

"Yes, I know."

She held his head against her, like a mother comforting a tired child.

It was good to be with Vana again. It was lonely, being a hated outcast, reviled, feared; a monster, hunted by all the world.

"There is still much to do, Vana."

"Yes. I know."

"So much more than I realized." He was trying to smile, but it was a wan, discouraged smile. "I don't think I've accomplished very much, Vana."

"But Sanjan!" she protested. "If it hadn't been for you, the world would have been at war by now."

"Yes, that's true," he agreed. "But I've only postponed it."

"But that's something, Sanjan." She shuddered. "A week or two of atomic war, with bombs falling, would have reduced the world to ruins."

"Just a postponement," he said bitterly. "Don't you see, they've all stopped thinking of war, just because they're so busy hunting Sanjan."

"But what you've destroyed—"

"Nothing at all," he said, "compared to the whole. They'd never even miss it. With me out of the way, within a few weeks they'd—"

"Sanjan! Don't talk like that!"

"I have just this one human body, Vana. Maybe I've had a lot of luck—not killing myself, or being killed, long before this."

"Sanjan, dear."

She could only hold him, try to comfort him. The woman's place, perhaps not fully to understand, but always to comfort, giving the strength of her spirit to the man.

"Sometimes I am afraid, Vana."

"No, Sanjan, you mustn't be."

"Not for myself. But the world is so big."

To leave the task uncompleted, that would be failure. So quickly the dread name of Sanjan would just be a memory and the world could resume its normal activities. It would go on, of course, just as it had before. That universal cry, "We need defense!" would sound again. And Sanjan knew there was truth in that, of course. Everyone, weak or strong, must have the means of war—or they all must have none.

"But if I should fail, Vana?"

"You will not. You cannot. It's too important, Sanjan."

And as she held him, caressing him, he felt a new strength; and presently he drew back from her arms and sat straight.

"I shall not fail, Vana."

"No, of course not, Sanjan."

"I shall go on and on, until it is done."

"But sometimes you must rest," she murmured.

"Yes, I do."

"Where?"

He smiled. "Wherever I am, or think that I would be." And then he gestured past the trees of the garden, out to where the setting sun laid a sheen of yellow and gold across the sky. "Sometimes I come and sleep, quite near here, Vana, to be near you. Somehow it seems less lonely."

"Where, Sanjan?"

He lowered his voice. "You remember that little cave, up there on the hill, where we used to play when we were children?"

"Smee's Cave?"

"Smee, the pirate. Remember?"

"He had a hook for a hand. I was so afraid of him—"

"And you were Wendy," Sanjan said. "And I was Peter Pan."

"And we had a little bell to ring. That was Tinker Bell, the fairy. Oh Sanjan, we were so happy then."

He held her close. "We will be happy again, Vana. That's what I'm trying to do—help to make the world a place where people can just be happy and not afraid."

For a time he was silent. Finally he said, "I was up in the Alps. I told them there that soon I would begin destroying, not just property, but the leaders of the nations themselves."

"Deliberate murder, Sanjan?"

"I know," he said. "And then I got to thinking. Which of the leaders can you actually blame? From my viewpoint, surely not our own President. He is doing his best, as he sees it."

"Yes, I suppose so," she agreed.

"I have threatened them, so that perhaps they'll think more in terms of compromise and less in terms of war. And if I killed some of them, what good would it really do? Others would step into their places. Things would go on just the same."

"But the world may change, Sanjan," Vana said. "At least, you are showing them the way."

"I know it. And I'll keep on."

His quick ears heard the sound of someone coming from Vana's house. His glance warned her. He drew back from the warmth of her arms. He stood up.

There was just a little glow of radiance where he had been....

CHAPTER VI

End of a Dream

Smee's Cave it was called. It had been one of the fancies of their childhood when love and peace and happiness had reigned in their lives. A few nights after he had talked with Vana in her garden, Sanjan came back, tired, and stretched himself to rest at the mouth of the cave. He had been in mid-Europe. After a day and night of careful investigating, he had caused a monstrous atomic explosion there. Factories crowded with bomb-bearing rockets had gone up, and many of the finished bombs themselves. But so many people had been killed; and so wide, so crowded an area was devastated by the deadly radioactivity that Sanjan decided it was almost as horrible as war itself.

Sanjan lay shuddering. And then with tired, wandering, drifting thoughts, he was thinking only of Vana. It was comforting, at least, to be here in the little cave so near her home, a hallowed little place, which now, to Sanjan, seemed a symbol of what most of mankind really wanted.

The sudden sound of a loose stone rattling brought him out of his drifting thoughts. He snapped into startled alertness; and then he turned and saw the figure of Vana with the moonlight on her as she came up the stony little path.

"Vana! Vana, dear!"

"You're here, Sanjan! Oh, I'm so glad! I just wanted to be near you—to hold you again."

"And I wanted you. Just you, Vana. Nothing else."

The moonlight wrapped them as they sat in the mouth of the cave.

Hardly any warning came to Sanjan. There was Vana's love, her arms around him, with perhaps some faint little sound intruding. Then it flashed to him that Vana had been tricked. She had been watched, and now had been followed here! The shapes of men were suddenly here in the shadows.

"Vana!"

He felt her start at his murmured warning. In an instant Sanjan freed himself from her arms and tried to leap to his feet. A man's low voice muttered to someone else and another man lunged forward, with his arm drawn back.

Simultaneously, Sanjan's wary, protective thoughts leaped! That mountaintop in Labrador! He could be there now and escape this attack. But the threshold opening before him drew together and closed as he heard Vana's frightened cry.

That fatal cry from Vana! She did not mean it, of course. It burst from her.

"Sanjan! Sanjan!"

He lingered, fearful that she might be hurt, with every instinct in him springing to her protection. He turned, momentarily, with no thought at all, except for her. Next, he was aware of a man's arm coming forward, a hand hurling something, and a liquid struck against his face with searing, acrid fumes choking him, and eating into his eyes with a searing pain up into his brain, like fire spreading there.

"Sanjan! Sanjan, dear! Go! Go!"

But to Sanjan there was no moonlight here now—no sight of Vana. Nothing was here but his whirling thoughts, and the burning horrible pain on his face, in his eyes, his brain, and a ring of muttering voices in the blackness around him.

"Watch out!" they cried. "Be careful of what he may do. Ah-h-h! We've got him!"

"No! Kill him now! We can kill him now!"

"Wait! Wait! He could have gone already, but he hasn't!"

Next came Vana's despairing cry, so that he tried to stumble in the darkness toward her. Labrador! He would be safe in that little hideout in Labrador....

But with the acid eating into his eyes, there was only the darkness of Sanjan's futile thoughts. There would be nothing but this eternal darkness for him now, in Labrador, or anywhere else. Alone there, he would be helpless.

"We've got him."

"He doesn't go! See, he stays here."

"We did it! Maybe a bullet wouldn't have killed him, but this did the business. He's helpless and he knows it!"

"What can a blind man do?"

Sanjan was murmuring, "Vana! Vana, dear."

Soon he found her. Down on the ground he found her, and she sobbed and held him....

"We've captured him at last. Send out the news, Jenkins. What a night's work for us! Send out the news! We've got Sanjan—we've got him alive and helpless!"

Like a wild beast, they had caught Sanjan, alive and subdued. Within an hour the world of civilization was ringing with it.

"Oh, Vana!"

"You can't go, Sanjan?"

"What's the use, now, Vana?"

The Valley of the Nile? The mountains of Carpathia? He could be there now, in the darkness. But he would be lost always in darkness.

What could he do, anywhere, just stumbling in the dark?

"They've got me, Vana. It's all over."

She held him. She was sobbing.

They let her hold him, through all those hours when all the world debated what to do with him. Study him? Experiment on him? Science wanted to do that. Or would he rebel?

Would he, with a last desperate effort, go somewhere?

Even though in the darkness of the blind, might he not seek out some world leader, try to assassinate him because of some crazed idea of vengeance?

The leaders of the world feared to let him live.

He must be destroyed.

And here in Smee's Cave, he clung in the darkness to Vana, in the warmth of her arms. They both heard the babble around them, but they hardly heeded it.

A little wooden runway had been erected, from the cave down to where a huge electronic furnace now yawned with its open pit of monstrous heat. And on the ragged, stony hillside here at dawn, a crowd of people now had gathered to witness the execution. Sanjan, the fiend, was going to his death....

Then as the eastern sky was brightening with the coming sun of a new day for the world, Sanjan heard a man's voice; and he could feel that the man was standing here before him and Vana.

"The decision is that you must die, Sanjan," the man announced.

"Yes," Sanjan said. "I realize it. Oh Vana, please don't cry."

His father came and spoke in a choked voice. "Sanjan, son!"

"Oh!... Hello, Dad."

"I fought so against the decision," his father was saying. "All night I've been fighting it. I've tried so hard."

"Thanks, Dad. And—good luck to you. Good luck to you all."

Then in the darkness he could feel Vana and his father being taken away from him....

The blood-colored sun of the new day was peering over the eastern horizon when Sanjan stood up and was guided to the runway. In the flush of pink dawn-light, the watching people on the hillside were suddenly hushed with awe as they stared at the lone figure. But some of them were murmuring to each other:

"Will the war come now?"

"If only he could have succeeded!"

"Impossible!"

"He has to die. He's a man ahead of his time!"

"But some day, John—"

"Yes, some day."

Slowly in the flush of the dawn, the lone figure moved down the runway. It was a ragged, almost pitiful figure now; but it moved steadily, with arms outstretched.

"Sanjan! Oh, Sanjan dear!" That was Vana's last little murmured cry as she clung to Robert Thome.

On the runway, Sanjan was walking slowly, steadily down.

Sometimes his outstretched hands touched the side rails to guide him. Just a ragged youth, blind and helpless.

But there was a radiance from him.

At last he reached the brink. He paused, with the glare and the heat of the furnace on him.

And then he took another step, and went down.

The radiance which was Sanjan mingled for just an instant with the monstrous, consuming fire of science—and was gone.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment