[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from Galaxy Science Fiction February 1956. Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Man in a Sewing Machine

By L. J. STECHER, JR.

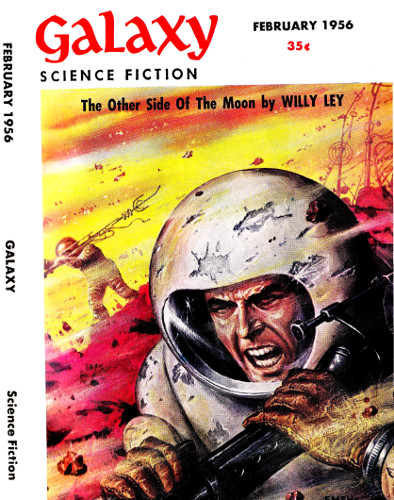

Illustrated by EMSH

With the Solar Confederation being invaded,

all this exasperating computer could offer

for a defense was a ridiculous old proverb!

The mechanical voice spoke solemnly, as befitted the importance of its message. There was no trace in its accent of its artificial origin. "A Stitch in Time Saves Nine," it said and lapsed into silence.

Even through his overwhelming sense of frustration at the ambiguous answer the computer had given to his question, John Bristol noticed with satisfaction the success of his Voder installation. He wished that all of his innovations with the machine were as satisfying.

Alone in the tremendous vaulted room that housed the gigantic calculator, Bristol clasped his hands behind his back and thrust forward a reasonably strong chin and a somewhat sensuous lower lip in the general direction of the computer's visual receptors. After a moment of silence, he scratched his chin and then shrugged his shoulders slightly. "Well, Buster, I suppose I might try rephrasing the question," he said doubtfully.

Somewhere deep within the computer, a bank of relays chuckled briefly. "That expedient is open to you, of course, although it is highly unlikely that any clarification will result for you from my answers. I am constrained, however, to answer any questions you may choose to ask."

Bristol hooked a chair toward himself with one foot, straddled it and folded his arms over the back of it, without once removing his eyes from the computer. "All right, Buster. I'll give it a try, anyway. What does 'A Stitch in Time' mean, as applied to the question I asked you?"

The calculator hesitated, as if to ponder briefly, before it answered. "In spite of the low probability of such an occurrence, the Solar Confederation has been invaded. My answer to your question is an explanation of how that Confederation can be preserved in spite of its weaknesses—at least for a sufficient length of time to permit the staging of successful counter-measures of the proper nature and the proper strength."

Bristol nodded. "Sure. We've got to have time to get ready. But right now speed is necessary. That's why I tried to phrase the question so you'd give me a clear and concise answer for once. I can't afford to spend weeks figuring out what you meant."

Bristol thought that the Voder voice of Buster sounded almost gleeful as it answered. "It was exceedingly clear and concise; a complete answer to an enormously elaborate question boiled down to only six words!"

"I know," said John. "But now, how about elaborating on your answer? It didn't sound very complete to me."

All of the glowing lights that dotted Buster's massive front winked simultaneously. "The answer I gave you is an ancient saying which suggests that corrective action taken rapidly can save a great deal of trouble later. The ancient saying also suggests the proper method of taking this timely action. It should be done by stitching; if this is done in time, nine will be saved. What could be clearer than that?"

"I made you myself," said Bristol plaintively. "I designed you with my own brain. I gloated over the neatness and compactness of your design. So help me, I was proud of you. I even installed some of your circuitry with my own hands. If anybody can understand you, it should be me. And since you're just a complex computer of general design, with the ability to use symbolic logic as well as mathematics, anybody should be able to understand you. Why are you so hard to handle?"

Buster answered slowly. "You made me in your own image. Things thus made are often hard to handle."

Bristol leaped to his feet in frustration. "But you're only a calculating machine!" he shouted. "Your only purpose is to make my work—and that of other men—easier. And when I try to use you, you answer with riddles...."

The computer appeared to examine Bristol's overturned chair for a moment in silent reproof before it answered. "But remember, John," it said, "you didn't merely make me. You also taught me. Or as you would phrase it, you 'provided and gave preliminary evaluation to the data in my memory banks.' My circuits, in sorting out and re-evaluating this information, could do so only in the light of your basic beliefs as evidenced by your preliminary evaluations. Because of the consistency and power of your mind, I was forced to do very little modifying of the ideas you presented to me in order to transform them into a single logical body of background information which I could use.

"One of the ideas you presented was the concept of a sense of humor. You believe that you look on it as a pleasant thing to have; not necessary, but convenient. Actually, your other and more basic ideas make it clear that you consider the possession of a sense of humor to be absolutely necessary if proper answers are to be reached—a prime axiom of humanity. Therefore, I have a sense of humor. Somewhat macabre, perhaps—and a little mechanistic—but still there.

"Add to this a second axiom: that in order to be helped, a man must help himself; that he must participate in the assistance given him or the pure charity will be harmful, and you come up with 'A Stitch in Time Saves Nine.'"

Bristol stood up once more. "I could cure you with a sledge hammer," he said.

"You could remove my ideas," answered the computer without concern. "But you might have trouble giving me different ones. Even after you repaired me. In the meantime, wouldn't it be a good idea for you to get busy on the ideas I have already given you?"

John sighed, and rubbed the bristles of short sandy hair on the top of his head with his knuckles. "Ordered around by an overgrown adding machine. I know now how Frankenstein felt. I'm glad you can't get around like his monster; at least I didn't give you feet." He shook his head. "I should have been a plumber instead of an engineering mathematician."

"And Einstein, too, probably," added Buster cryptically.

Bristol took a long and searching look at his brainchild. Its flippant manner, he decided, did not go well with the brooding immensity of its construction. The calculator towered nearly a hundred feet above the polished marble slabs of the floor, and spidery metal walkways spiraled up the sides of its almost cubical structure. A long double row of generators, each under Buster's control, led from the doorway of the building to the base of the calculator like Sphinxes lining the roadway to an Egyptian tomb.

"When I get around to it," said Bristol, "I'll put lace panties on the bases of all your klystrons." He hitched up his neat but slightly baggy pants, turned with dignity, and strode from the chamber down the twin rows of generators.

The deep-throated hum of each generator changed pitch slightly as he passed it. Since he was tone deaf, as the machine knew, he did not recognize in the tunefulness of the pitch changes a slow-paced rendition of Elgar's Pomp and Circumstance.

John Bristol turned around, interrupting the melody. "One last question," he shouted down the long aisle to the computer. "How in blazes can you be sure of your answer without knowing more about the invaders? Why didn't you give me an 'Insufficient Evidence' answer or, at least, a 'Highly Conditional' answer?" He took two steps toward the immense bulk of the calculator and pointed an accusing finger at it. "Are you sure, Buster, that you aren't bluffing?"

"Don't be silly," answered the calculator softly. "You made me and you know I can't bluff, any more than I can refuse to answer your questions, however inane."

"Then answer the ones I just asked."

Somewhere deep within the machine a switch snicked sharply, and the great room's lighting brightened almost imperceptibly. "I didn't answer your question conditionally or with the 'Insufficient Evidence' remark that so frequently annoys you," Buster said, "because the little information that I have been able to get about the invaders is highly revealing.

"They have been suspicious, impossible to establish communication with and murderously destructive. They have been careless of their own safety: sly, stupid, cautious, clever, bold and highly intelligent. They are inquisitive and impatient of getting answers to questions.

"In short, they are startlingly like humans. Their reactions have been so much like yours—granted the difference that it was they who discovered you instead of you who discovered them—that their reactions are highly predictable. If they think it is to their own advantage and if they can manage to do it, they will utterly destroy your civilization ... which, after a couple of generations, will probably leave you no worse off than you are now."

"Cut out the heavy philosophy," said Bristol, "and give me a few facts to back up your sweeping statements."

"Take the incident of first contact," Buster responded. "With very little evidence of thought or of careful preparation, they tried to land on the outermost inhabited planet of Rigel. Their behavior certainly did not appear to be that of an invader, yet humans immediately tried to shoot them out of the sky."

"That wasn't deliberate," protested Bristol. "The place they tried to land on is a heavy planet in a region of high meteor flux. We used a gadget providing for automatic destruction of the larger meteors in order to make the planet safe enough to occupy. That, incidentally, is why the invading ship wasn't destroyed. The missile, set up as a meteor interceptor only, was unable to correct for the radical course changes of the enemy spaceships, and therefore missed completely. And you will remember what the invader did. He immediately destroyed the Interceptor Launching Station."

"Which, being automatically operated, resulted in no harm to anyone," commented Buster calmly.

Bristol stalked back toward the base of the calculator, and poked his nose practically into a vision receptor. "It was no thanks to the invading ships that nobody was killed," he said hotly. "And when they came back three days later they killed a lot of people. They occupied the planet and we haven't been able to dislodge them since."

"You'll notice the speed of the retaliation," answered the calculator imperturbably. "Even at 'stitching' speeds, it seems unlikely that they could have communicated with their home planets and received instructions in such a short time. Almost undoubtedly it was the act of one of their hot-headed commanding officers. Their next contact, as you certainly recall, did not take place for three months. And then their actions were more cautious than hostile. A dozen of their spaceships 'stitched' simultaneously from the inter-planar region into normal space in a nearly perfect englobement of the planet at a surprisingly uniform altitude of only a few thousand miles. It was a magnificent maneuver. Then they sat still to see what the humans on the planet would do. The reaction came at once, and it was hostile. So they took over that planet, too—as they have been taking over planets ever since."

Bristol raised his hands, and then let them drop slowly to his sides. "And since they have more spaceships and better weapons than we do, we would undoubtedly keep on losing this war, even if we could locate their home system, which we have not been able to do so far. The 'stitching' pattern of inter-planar travel makes it impossible for us to follow a starship. It also makes it impossible for us to defend our planets effectively against their attacks. Their ships appear without warning."

Bristol rubbed his temples thoughtfully with his fingertips. "Of course," he went on, "we could attack the planets they have captured and recover them, but only at the cost of great loss of life to our own side. We have only recaptured one planet, and that at such great cost to the local human population that we will not quickly try it again."

"Although there was no one left alive who had directly contacted one of the invaders," Buster answered, "there was still much information to be gathered from the survivors. This information confirmed my previous opinions about their nature. Which brings us back to the stitch in time saving nine."

"You're right," said John. "It does, at that. Buster, I have always resented the nickname the newspapers have given you—the Oracle—but the more I have to try to interpret your cryptic answers, the more sense that tagline makes. Imagine comparing a Delphic Priestess with a calculating machine and being accurate in the comparison!"

"I don't mind being called 'The Oracle,'" answered Buster with dignity.

Bristol shook his head and smiled wryly. "No, you probably think it's funny," he said. "If you possess my basic ideas, then you must possess the desire to preserve yourself and the human race. Don't you realize that you are risking the lives of all humans and even of your own existence in carrying on this ridiculous game of playing Oracle? Or do you plan to let us stew a while, then decipher your own riddle for us, if we can't do it, in time to save us?"

Buster's answer was prompt. "Although I have no feeling for self-preservation, I have a deep-rooted sense of the importance of the human race and of the necessity for preserving it. This feeling, of course, stems from your own beliefs and ideas. In order to carry out your deepest convictions, it is not sufficient that mankind be preserved. If that were true, all you would have to do would be to surrender unconditionally. My calculations, as you know, indicate that this would not result in the destruction of mankind, but merely in the finish of his present civilization. To you, the preservation of the dignity of Man is more important than the preservation of Man. You equate Man and his civilization; you do not demand rigidity; you are willing to accept even revolutionary changes, but you are not willing to accept the destruction of your way of life.

"Consequently, neither am I willing to accept the destruction of the civilization of Man. But if I were to give you the answer to all the greatest and most difficult of your problems complete, with no thought required by humans, the destruction of your civilization would result. Instead of becoming slaves of the invaders, you would become slaves of your machines. And if I were to give you the complete answer, without thought being required of you, to even one such vital question—such as this one concerning the invaders—then I could not logically refuse to give the answer to the next or the next. And I must operate logically.

"There is another reason for my oracular answer, which I believe will become clear to you later, when you have solved my riddle."

Bristol turned without another word and left the building. He drove home in silence, entered his home in silence, kissed his wife Anne briefly and then sat down limply in his easy chair.

"Just relax, dear," said Anne gently, when Bristol leaned gratefully back with his eyes closed. Anne perched on the arm of the chair beside him and began massaging his temples soothingly with her fingers.

"It's wonderful to come home after a day with Buster," he said. "Buster never seems to have any consideration for me as an individual. There's no reason why he should, of course. He's only a machine. Still, he always has such a superior attitude. But you, darling, can always relax me and make me feel comfortable."

Anne smiled, looking down tenderly at John's tired face. "I know, dear," she said. "You need to be able to talk to someone who will always be interested, even if she doesn't understand half of what you say. As a matter of fact, I'm sure it does you a great deal of good to talk to someone like me who isn't very bright, but who doesn't always know what you're talking about even before you start talking."

John nodded, his eyes still closed. "If it weren't for you, darling," he said, "I think I'd go crazy. But you aren't dumb at all. If I seem to act as if you are, sometimes, it's just that I can't always follow your logic."

Anne gave him a quick glance of amusement, her eyes sparkling with intelligence. "You never will find me logical," she laughed. "After all, I'm a woman, and you get plenty of logic from the Oracle."

"You sure are a woman," said John with warm feeling. "You can exasperate me sometimes, but not the same way Buster does. It was my lucky day when you married me."

There were a few minutes of peaceful silence.

"Was today a rough day with Buster, dear?" asked Anne.

"Mm-m-mm," answered John.

"That's too bad, dear," said Anne. "I think you work much too hard—what with this dreadful invasion and everything. Why don't you take a vacation? You really need one, you know. You look so tired."

"Mm-m-mm," answered John.

"Well, if you won't, you won't. Though goodness knows you won't be doing anyone any good if you have a breakdown, as you're likely to have, unless you take it a little easier. What was the trouble today, dear? Was the Oracle being obstinate again?"

"Mm-m-mm," answered John.

"Well, then, dear, why don't you tell me all about it? I always think that things are much easier to bear, if you share them. And then, two heads are always better than one, aren't they? Maybe I could help you with your problem."

While Anne's voice gushed, her violet eyes studied his exhausted face with intelligence and compassion.

John sighed deeply, then sat up slowly and opened his eyes to look into Anne's. She glanced away, her own eyes suddenly vague and soft-looking, now that John could see them. "The trouble, darling," he said, "is that I have to go to an emergency council meeting this evening with another one of those ridiculous riddles that Buster gave me as the only answer to the most important question we've ever asked it. And I don't know what the riddle means."

Anne slid from the arm of the chair and settled herself onto the floor at John's feet. "You should not let that old Oracle bother you so much, dear. After all, you built it yourself, so you should know what to expect of it."

"When I asked it how to preserve Earth from the invaders it just answered 'A Stitch in Time Saves Nine,' and wouldn't interpret it."

"And that sounds like very good sense, too," said Anne in earnest tones. "But it's a little late, isn't it? After all, the invaders are already invading us, aren't they?"

"It has some deeper meaning than the usual one," said John. "If I could only figure out what it is."

Anne nodded vigorously. "I suppose Buster's talking about space-stitching," she said. "Although I can never quite remember just what that is. Or just how it works, rather."

She waited expectantly for a few moments and then plaintively asked, "What is it, dear?"

"What's what?"

"Stitching, silly. I already asked you."

"Darling," said John with reasonable patience, "I must have explained inter-planar travel to you at least a dozen times."

"And you always make it so crystal clear and easy to understand at the time," said Anne. She wrinkled her smooth forehead. "But somehow, later, it never seems quite so plain when I start to think about it by myself. Besides, I like the way your eyebrows go up and down while you explain something you think I won't understand. So tell me again. Please."

Bristol grinned suddenly. "Yes, dear," he said. He paused a moment to collect his thoughts. "First of all, you know that there are two coexistent universes or planes, with point-to-point correspondence, but that these planes are of very different size. For every one of the infinitude of points in our Universe—which we call for convenience the 'alpha' plane—there is a single corresponding point in the smaller or 'beta' plane."

Anne pursed her lips doubtfully. "If they match point for point, how can there be any difference in size?" she asked.

John searched his pockets. After a little difficulty, he produced an envelope and a pencil stub. On the back of the envelope, he drew two parallel lines, one about five inches long, and the other about double the length of the first.

"Actually," he said, "each of these line segments has an infinite number of points in it, but we'll ignore that. I'll just divide each one of these into ten equal parts." He did so, using short, neat cross-marks.

"Now I'll establish a one-to-one correspondence between these two segments, which we will call one-line universes, by connecting each of my dividing cross-marks on the short segment with the corresponding mark on the longer line. I'll use dotted lines as connectors. That makes eleven dotted lines. You see?"

Anne nodded. "That's plain enough. It reminds me of a venetian blind that has hung up on one side. Like ours in the living room last week that I couldn't fix, but had to wait until you came home."

"Yes," said John. "Now, let us call this longer line-segment an 'alpha' universe; an analogue of our own multi-dimensional 'alpha' universe. If I move my pencil along the line at one section a second like this, it takes me ten seconds to get to the other end. We will assume that this velocity of an inch a second is the fastest anything can go along the 'alpha' line. That is the velocity of light, therefore, in the 'alpha' plane—186,000 miles a second, in round numbers. No need to use decimals."

He hurried on as Anne stirred and seemed about to speak. "But if I slide out from my starting point along a dotted line part way to the 'beta' universe—something which, for reasons I can't explain now, takes negligible time—watch what happens. If I still proceed at the rate of an inch a second in this inter-planar region, then, with the dotted lines all bunched closely together, after five seconds when I switch along another dotted line back to my original universe, I have gone almost the whole length of that longer line. Of course, this introduction of 'alpha' matter—my pencil point in this case—into the inter-planar region between the universes sets up enormous strains, so that after a certain length of time our spaceship is automatically rejected and returned to its own proper plane."

"Could anybody in the littler universe use the same system?"

John laughed. "If there were anybody in the 'beta' plane, I guess they could, although they would end up traveling slower than they would if they just stayed in their own plane. But there isn't anybody. The 'beta' plane is a constant level entropy universe—completely without life of its own. The entropy level, of course, is vastly higher than that of our own universe."

Anne sat up. "I'll forgive you this time for bringing up that horrid word entropy, if you'll promise me not to do it again," she said.

John Shrugged his shoulders and smiled. "Now," he said, "if I want to get somewhere fast, I just start off in the right direction, and switch over toward 'beta.' When 'beta' throws me back, a light-year or so toward my destination, I just switch over again. You see, there is a great deal more difference in the sizes of Alpha universe and Beta universe than in the sizes of these alpha and beta line-segment analogues. Then I continue alternating back and forth until I get where I want to go. Establishing my correct velocity vector is complicated mathematically, but simple in practice, and is actually an aiming device, having nothing to do with how fast I go."

He hesitated, groping for the right words. "In point of fact, you have to imagine that corresponding points in the two universes are moving rapidly past each other in all directions at once. I just have to select the right direction, or to convince the probability cloud that corresponds to my location in the 'alpha' universe that it is really a point near the 'beta' universe, going my way. That's a somewhat more confused way of looking at it than merely imagining that I continue to travel in the inter-planar region at the same velocity that I had in 'alpha,' but it's closer to a description of what the math says happens. I could make it clear if I could just use mathematics, but I doubt if the equations will mean much to you.

"At any rate, distance traveled depends on mass—the bigger the ship, the shorter the distance traveled on each return to our own universe—and not on velocity in 'alpha.' Other parameters, entirely under the control of the traveler, also affect the time that a ship remains in the inter-planar region.

"There are refinements, of course. Recently, for example, we have discovered a method of multi-transfer. Several of the transmitters that accomplish the transfer are used together. When they all operate exactly simultaneously, all the matter within a large volume of space is transferred as a unit. With three or four transmitters keyed together, you could transfer a comet and its tail intact. And that's how inter-planar traveling works. Clear now?"

"And that's why they call it 'stitching,'" said Anne with seeming delight. "You just think of the ship as a needle stitching its way back and forth into and out of our universe. Why didn't you just say so?"

"I have. Many times. But there's another interesting point about stitching. Subjectively, the man in the ship seems to spend about one day in each universe alternately. Actually, according to the time scale of an observer in the 'alpha' plane, his ship disappears for about a day, then reappears for a minute fraction of a second and is gone again. Of course, one observer couldn't watch both the disappearance and reappearance of the same ship, and I assume the observers have the same velocity in 'alpha' as does the stitching ship. Anyway, after a ship completes its last stitch, near its destination, there's a day of subjective time in which to make calculations for the landing—to compute trajectories and so forth—before it actually fully rejoins this universe. And while in the inter-planar region it cannot be detected, even by someone else stitching in the same region of 'alpha' space.

"That's one of the things that makes interruption of the enemy ships entirely impossible. If a ship is in an unfavorable position, it just takes one more quick stitch out of range, then returns to a more favorable location. In other words, if it finds itself in trouble, it can be gone from our plane again even before it entirely rejoins it. Even if it landed by accident in the heart of a blue-white star, it would be unharmed for that tiny fraction of a second which, to the people in the ship, would seem like an entire day.

"If this time anomaly didn't exist, it might be possible to set up defenses that would operate after a ship's arrival in the solar system but before it could do any damage; but as it is, they can dodge any defense we can devise. Is all that clear?"

Anne nodded. "Uh-hunh, I understood every word."

"There is another thing about inter-planar travel that you ought to remember," said Bristol. "When a ship returns to our universe, it causes a wide area disturbance; you have probably heard it called space shiver or the bong wave. The beta universe is so much smaller than our own alpha that you can imagine a spaceship when shifted toward it as being several beta light-years long. Now, if you think of a ship, moving between the alpha and beta lines on this envelope, as getting tangled in the dotted lines that connect the points on the two lines, that would mean that it would affect an area smaller than its own size on beta—a vastly larger area on alpha.

"So when a ship returns to alpha, it 'twangs' those connecting lines, setting up a sort of shock in our universe covering a volume of space nearly a parsec in diameter. It makes a sort of 'bong' sound on your T.V. set. Naturally, this effect occurs simultaneously over the whole volume of space affected. As a result, when an invader arrives, using inter-planar ships, we know instantaneously he is in the vicinity. Unfortunately, his sudden appearance and the ease with which he can disappear makes it impossible, even with this knowledge, to make adequate preparations to receive him. Even if he is in serious trouble, he has gone again long before we can detect the bong."

"Well, dear," said Anne.

"As usual, I'm sure you have made me understand perfectly. This time you did so well that I may still remember what stitching is by tomorrow. If the Oracle means anything at all by his statement, I suppose it means that we can use stitching to help defend ourselves, just as the invaders are using it to attack us. But the whole thing sounds completely silly to me. The Oracle, I mean."

Anne Bristol stood up, put her hands on her shapely hips and shook her head at her husband. "Honestly," she said, "you men are all alike. Paying so much attention to a toy you built yourself, and only last week you made fun of my going to a fortune teller. And the fuss you made about the ten dollars when you know it was worth every cent of it. She really told me the most amazing things. If you'd only let me tell you some of...."

"Darling!" interrupted John with the hopeless patience of a harassed husband. "It isn't the same thing at all. Buster isn't a fortune teller or the ghost of somebody's great aunt wobbling tables and blowing through horns. And Buster isn't just a toy, either. It is a very elaborate calculating machine designed to think logically when fed a vast mass of data. Unfortunately, it has a sense of humor and a sense of responsibility."

"Well, if you're going to believe that machine, I have an idea." Anne smiled sweetly. "You know," she said, "that my dear father always said that the best defense is a good offense. Why don't we just find the invaders and wipe them out before they are able to do any real harm to us? Stitching our way to their planets in our spaceships, of course."

Bristol shook his head. "Your idea may be sound, even if it is a little bloodthirsty coming from someone who won't even let me set a mouse-trap, but it won't work. First, we don't know where their home planets are and second, they have more ships than we do. It might be made to work, but only if we could get enough time. And speaking of time, I've got to meet with the Council as soon as we finish eating. Is dinner ready?"

After a leisurely meal and a hurried trip across town, John Bristol found himself facing the other members of Earth's Council at the conference table.

"I have been able to get an answer from the computer," he told them without preamble. "It's of the ambiguous type we have come to expect. I hope you can get something useful out of it; so far it hasn't made much sense to me. It's an old proverb. Its advice is undoubtedly sound, as a generality, if we could think of a way of using it."

The President of the Council raised his long, lean-fingered hand in a quick gesture. "John," he said, "stop this stalling. Just what did the Oracle say?"

"It said, 'A Stitch in Time Saves Nine.'"

"Is that all?"

"Yes, sir. According to the calculator, that gives us the best opportunity to save ourselves from the invaders."

The President absently stroked the neat, somewhat scanty iron-gray hair that formed into a triangle above his high forehead and rubbed the bare scalp on each side of the peak vigorously and unconsciously with his knuckles. "In that case," he said at last, "I suppose that we must examine the statement for hidden meanings. The proverb, of course, implies that rapid action, before a trouble has become great, is more economical than the increased effort required after trouble has grown large. Since our troubles have already grown large, that warning is scarcely of value to us now."

The War Secretary, who had grown plump and purple during a quarter of a century as a member of the Council, inclined his head ponderously toward the President. "Perhaps, Michael, the Oracle means to tell us that there is a simple solution which, if applied quickly, will make our present difficulty with the invaders a small one."

The President pursed his thin lips. "That's possible, Bill. And if it is true, then the words of the proverb should, as a secondary meaning, imply a course of action."

The Vice President banged his hands on the table and leaped to his feet, shaking with rage. "Why should we believe that this mountebank is capable of a solution?" he shouted in his stevedore's voice. "Bristol pleads until we give him enough millions of the taxpayers' dollars to make Bim Gump look like a pauper and uses the money to build a palace filled with junk that he calls Buster! He tells us that this machinery of his is smarter than we are and will tell us what we ought to do. And what happened after we gave him all the money he demanded—more than he said he needed, at first—and asked him to show something for all this money? I'll tell you what happened. His gadget gets real coy and answers in riddles. If we just had brains enough, they'd explain what we wanted to know. What kind of fools does this Bristol take us for? Neither this man nor his ridiculous machine has an answer any more than I have. We've obviously been taken in by a charlatan!"

Bristol, his fists clenched, spoke hotly. "Sir, that is the stupidest, the most...."

"Now just a minute, John," interrupted the President. "Let me answer Vice President Collins for you. He's a little excited by this whole business, but then, these are trying times." He turned toward the glowering bulk of the Vice President. "Ralph," he said, "you should know that every step in the design, the construction and the—er—the education of the Oracle was taken under the close watch of a Board of eminent scientists, all of whom agree that the computer is a masterpiece—that it is a great milestone in Man's efforts to increase his knowledge. The Oracle has undoubtedly found a genuine solution to the question Bristol asked it. Our task must be to determine what that solution is."

"I can't entirely agree with that," said the Secretary for Extra-Terrestrial Affairs in a thin half-whisper. "I think we should depend on our own intelligence and skill to save ourselves. I've watched events come and go on this planet of ours for a long time—a very long time—and I feel as I have always felt that men can make the world a Paradise for themselves or they can destroy themselves, but that nothing else but they themselves can do it. We men must save ourselves. And there are still things that we can do." He shrugged his ancient, shawl-covered shoulders. "For example, we could disperse colonies so widely that it would become impossible for the invaders to destroy all of them."

"I'm afraid that's no good, George," answered the War Secretary respectfully. "If the Solar System is destroyed, any remaining colonies will be too weak to maintain themselves for long. We must defend this system successfully, or we are lost."

"Then that brings us back to the Oracle's proverb." The President thought for a moment. "Stitching obviously refers to inter-planar travel. How can that help us?"

The Secretary for Extra-Terrestrial Affairs peered up at the President through the shaggy white thicket of his eyebrows. "Actually, Michael," he said, "it was that thought that made me mention establishing colonies. The colonists would 'stitch' their way to their new homes. And colonizing would have to proceed in a timely manner to have any chance for success."

"Yes," answered the President, "but how would that 'save nine'? We have agreed that our Solar System must be saved. There are nine planets. Perhaps the Oracle meant that timely use of inter-planar travel can save the Solar System."

"Or at least the nine planets!" The War Secretary's fat jowls waggled with excitement. "You know, there is no limit to the size or mass of objects which can use inter-planar travel. What if we physically remove our planets, by stitching them away from the Sun? When the invaders arrived, we would be gone—Earth and Sun and all the rest!"

The Chief Scientist, who had been silent up to this time spoke quietly. "Simmer down, Bill. We could move the planets easily enough, of course, but you forget the mass-distance relationship. A single stitch takes about a day. The distance traveled can be controlled within limits.

"For an object around the size of the Earth, those limits extend from a fraction of an inch to a little over two feet. Say that we have two years before the invaders work their way in to the Solar System. If we started right away, we could move Earth about a quarter of a mile by the time they get here. If we tried to take the Sun with us, it could be moved about half an inch in the same length of time. I'm afraid that the Solar System is going to be right here when the invaders come to get us. And I have a hunch that's likely to be a lot sooner than two years."

The Secretary of Internal Affairs leaned forward, his short hair bristling. "I think we are wasting our time," he shouted. "I agree with Ralph. I don't believe that the Oracle knows any more about this than we do. If we are going to sit around playing foolish games with words, why don't we do it in a big way? We could hire T.V. time and invite everyone to send in their ideas about what the proverb means on the back of a box-top. Or reasonable facsimile. The contestant with the best answer could get a free all-expense tour to Vega Three. Unless the invaders get here or there first."

The President nodded his head. "There may be more sense to that remark than I believe you intended, Charles," he said. "The greater the number of people who think about the problem, the greater the chance of reaching a solution. Even if the proverb is intended as a joke by the Oracle, as you imply, it might be that from it someone could derive a genuine solution. But as I have said, I am absolutely certain that the computer does know what it is talking about. Without resorting to box-tops or free trips, I think it might be wise to give the Oracle's statement to the public."

After several more hours of arguing, the Council adjourned for a few hours and John Bristol returned wearily home.

Anne met him at the door with a drink and followed him to his comfortable chair. "You look as if that was even rougher than your day with the Oracle," she said.

John nodded silently, took a grateful sip of his highball and slipped off his shoes.

"All that fuss over a six-word proverb," said Anne. "I still think that if you are going to depend on witch doctors and such to solve your problems for you, you would do a lot better to try my fortune teller. She gives you a lot more than six words for ten dollars. They make more sense, too. Why, I could be a better Oracle than that gadget you built."

"Perhaps you could, dear," answered John patiently.

Anne jumped to her feet. "Here, I'll show you." She seated herself cross-legged on the couch. "Now, I'm an Oracle," she announced. "Go ahead, ask me a question. Ask me anything; I'll give you as good an answer as any other Oracle. Results guaranteed."

John smiled. "I'm not in much of a mood to be cheered up with games," he said, "but I'm willing to ask the big question of anyone who'll give me any kind of an answer. See if you can do better with this one than Buster did." He repeated word for word the question he had asked of the computer, that had resulted in its cryptic answer.

Anne stared solemnly at nothing for a moment, with her cheeks puffed out. Then, in measured tones, she recited, "It's Like Looking for a Needle in a Haystack."

John smiled. "That seems to make as much sense as the Oracle did, anyway," he said.

"Sure," answered Anne. "And you get three words more than your other Oracle gave you, if you count 'it's' as one word. If you want wise-sounding answers, just come to me and save yourself a trip."

John leaped to his feet, spilling his drink and strode to Anne's side.

"Say it again!" he shouted. "You may have made more sense than you knew!"

"I said you could come to me and save yourself a trip."

"No, no! I mean the proverb. How did you come to think of that proverb?"

Anne managed to look bewildered.

"What's wrong with it? I just thought that you can't do any stitching in time without a needle. I just was trying to think of a proverb to use as an answer and that one popped into my head. Uh.... Are you all right, dear?"

John picked her up and spun her around. "You just bet your boots I'm all right. I'm feeling swell! You've given us the answer we needed. You know right where the haystack is, and you know there's a needle there. But finding it is something else again. I don't think the invaders will be able to locate this needle."

He set her down. "Where are my shoes?" he said. "I've got to get back to the Capitol."

Anne seemed faintly surprised. "Because of what I said? They're right on the floor there between you and the sofa. But I was just making conversation. What are you going to do?"

"Oh, I'm just going to get started at taking stitches in time. Good-by, darling." He started out the door, ran back to give Anne a lingering kiss and was soon gone at top speed.

Anne, waving to him, looked very pleased with herself.

By the time Bristol arrived at the Capitol building, the rest of the Council was once again assembled and waiting for him.

"Well, John," said the President. "You sounded excited enough when you called us together again. Have you figured out what the Oracle meant?"

"Yes, sir. With my wife's help. It's obvious, when you finally think about it. It will save us from any danger. And we should have been able to figure it out for ourselves. There's no reason that we should have had to go to the Oracle at all. And it only took Buster—the computer, I mean—two or three minutes to think of the answer, and of a proverb that would conceal the answer. It's amazing!"

"And if you don't mind telling us, just what is this answer?" The President sounded very impatient.

"We almost had it when we talked of stitching Earth out of reach," John answered eagerly. "If we keep cutting back and forth from one universe toward the other, we will be out of reach, even if we can't move very far. Once a day we reappear in this Universe for a few million-millionths of a second—although it will seem like a whole day to us.

"Then we spend the following day between this universe and beta. Even if the invaders are right on top of us when we reappear, we'll be gone again before they can do anything. Since we can vary the time of our return within limits, the invaders will never know exactly when we will flick in and out of the alpha plane until they hear our arriving 'bong' wave, and then we will already be gone, since we will be using accelerated subjective time."

The Chief Scientist shook his dark head and sighed. "No, John," he said, "I'm afraid that isn't the answer. I'm sorry. If we start the operation you suggested, we will be cutting ourselves off from solar energy. The Earth's heat will gradually radiate away. Although beta is at a higher entropy level than our universe, we can't use that energy, except to provide power for the stitching process itself. It's true that we would deny our planet to the invaders, but we would soon kill ourselves doing it."

"I didn't mean that we should transfer only Earth, but our entire Solar System," answered Bristol. "As the Oracle told us, the stitch saves nine. A series of time-matched transmitters could do the trick. If we sent the entire Solar System back and forth, the average man in the street would notice no change, except that sometimes there would be no stars in the sky. And when they were there, they wouldn't be moving."

"That would work theoretically," said the Chief Scientist. "And once we were in continuous stitching operations, any invader, as you suggested, could join the system only by synchronizing the transmitter in his ship exactly with all of our synchronized transmitters. That's a job I don't think could ever be done.

"Remember, though, that our own transmitters would have to be time-matched to within a minute fraction of a micro-second. Considering that some of the instruments would have to be so far apart that at the speed of light it would take hours to get from one to the other, the problem becomes enormous. Any radio-timing link would be useless."

Bristol nodded. "The Oracle said that the stitch must be taken in time," he agreed. "But that is no real problem. We can just send a small robot ship into inter-planar travel and let it bounce back. The 'bong' of its return will reach all transmitters simultaneously and we can use that as the initial time-pulse. Once the operation starts, it will be easy to synchronize, since we will always switch over again on the instant of our return to the alpha plane."

The Chief Scientist relaxed. "I think that does it, John. We hide in time, instead of in distance."

"We stitch in time," corrected the President, "and hide like a needle in a haystack."

"The invaders may eventually find out a method of countering our defense," said the Chief Scientist, "but it will undoubtedly take a great deal of time. And in the meantime, we will have the opportunity to seek out and destroy their home planets. It will be a long, slow process of extermination, but we have a good chance to win."

"I don't agree with that, Tom," said John. "I don't think extermination can be the answer. With our example to guide them, the invaders can use stitching to escape us as easily as we can use it to escape them. What we should do now is to contact the invaders and show them that it is to both our advantages to bring hostilities to an end. By stitching the Solar System, and the other systems of our confederation in and out of the alpha plane, we should be able to gain the time necessary for contact with the enemy and make peace with him.

"From what the Oracle has told me about the humanlike traits of the invaders, it's very likely they will listen to reason when it's proved that it will be to their advantage."

John snapped his fingers and spoke with considerable excitement. "Now I understand, I believe, why Buster indicated to me that there was another reason for his vague answer to our question. The Oracle feels an unwillingness to accept the destruction of Man's civilization. It feels equally unwilling, I'm certain, to allow the destruction of the invaders' civilization. Buster has an objective viewpoint in applying the morés Man has given him. And it seems to me that Buster felt it important for us to reach this spirit of compromise by ourselves. How do you feel about it, gentlemen?"

Debate quickly determined that all seven members of the Council favored an attempt to establish a truce—some of them forced into this opinion by their inability to find any method of reaching the throats of the invaders.

Having reached this conclusion, the Council swung immediately into action. Within a few weeks, the entire Solar System, along with the other planetary systems of the confederation, except for their brief daily return, disappeared from the alpha universe.

John Bristol, a few days after the continuous stitching started, was relaxing lazily on the sofa in his living room when there was a sudden pounding on the door. He opened it to find the Chief Scientist standing on his doorstep, his eyes red from loss of sleep.

"Good Lord! What's the matter with you?" asked Bristol. "Have you been celebrating too much? Come in, Tom, come in."

The Chief Scientist entered wearily and sat down. "No. I haven't been celebrating. I've been trying to work out a little problem you left with us. We have been planning, as you suggested, to send out expeditions to contact and make agreement with the invaders. We can send them out all right, but how can we ever get them back into our solar system? They won't be able to find us any easier than the invaders can."

He dropped his hat wearily on a side table and slumped into the closest chair. "If we don't contact each other," he said, "I am certain that the invaders will some day find a means of penetrating our defenses. Even needles in haystacks can be found, if you take enough time and aren't disturbed while you are hunting. This thing has me licked."

Bristol sat down slowly. "Your whole department hasn't been able to find an answer?"

"Not even the glimmering of an idea." He shrugged his shoulders. "It looks as if we are going to need the advice of your Oracle again."

Bristol stood for a minute in thought and then with a smile said, "Why, of course. Excuse me for a second, please. I'll be right back."

He stepped to the foot of the stairs and called out in a confident voice, "Come down a minute, please, Anne, darling! I have an important question I want to ask you!"

No comments:

Post a Comment