DAUGHTER

A Sequel to MOTHER

By PHILIP JOSÉ FARMER

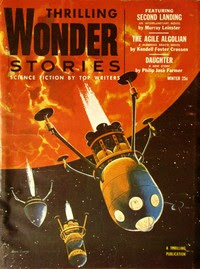

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Thrilling Wonder Stories Winter 1954.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Philip José Farmer @ Amazon

CQ! CQ!

This is Mother Hardhead pulsing.

Keep quiet, all you virgins and Mothers, while I communicate. Listen,

listen, all you who are hooked into this broadcast. Listen, and I

will tell you how I left my Mother, how my two sisters and I grew

our shells, how I dealt with the olfway, and why I have become the

Mother with the most prestige, the strongest shell, the most powerful

broadcaster and beamer, and the pulser of a new language.

First, before I tell my story, I will reveal to all you who do not know

it that my father was a mobile.

Yes, do not be nervequivered. That is a so-story. It is not a

not-so-story.

Father was a mobile.

Mother pulsed, "Get out!"

Then, to show she meant business, she opened her exit-iris.

That sobered us up and made us realize how serious she was. Before,

when she snapped open her iris, she did it so we could practise pulsing

at the other young crouched in the doorway to their Mother's wombs,

or else send a respectful message to the Mothers themselves, or even

a quick one to Grandmother, far away on a mountainside. Not that she

received, I think, because we young were too weak to transmit that far.

Anyway, Grandmother never acknowledged receipt.

At times, when Mother was annoyed because we would all broadcast at

once instead of asking her permission to speak one at a time or because

we would crawl up the sides of her womb and then drop off the ceiling

onto the floor with a thud, she would pulse at us to get out and build

our own shells. She meant it, she said.

Then, according to our mood, we would either settle down or else get

more boisterous. Mother would reach out with her tentacles and hold us

down and spank us. If that did no good, she would threaten us with the

olfway. That did the trick. That is until she used him too many times.

After a while, we got so we didn't believe there was an olfway. Mother,

we thought, was creating a not-so-story. We should have known better,

however, for Mother loathed not-so-stories.

Another thing that quivered her nerves was our conversation with Father

in Orsemay. Although he had taught her his language, he refused to

teach her Orsemay. When he wanted to send messages to us that he knew

she wouldn't approve, he would pulse at us in our private language.

That was another thing, I think, that finally made Mother so angry she

cast us out despite Father's pleadings that we be allowed to remain

four more seasons.

You must understand that we virgins had remained in the womb far longer

than we should have. The cause for our overstay was Father.

He was the mobile.

Yes, I know what you're going to reply. All fathers, you will repeat,

are mobiles.

But he was father. He was the pulsing mobile.

Yes, he could, too. He could pulse with the best of us. Or maybe he

himself couldn't. Not directly. We pulse with organs in our

body. But Father, if I understand him correctly, used a creature of

some kind which was separate from his body. Or maybe it was an organ

that wasn't attached to him.

Anyway, he had no internal organs or pulse-stalks growing from him to

pulse with. He used this creature, this r-a-d-i-o, as he called it. And

it worked just fine.

When he conversed with Mother, he did so in Motherpulse or in his

own language, mobile-pulse. With us he used Orsemay. That's like

mobile-pulse, only a little different. Mother never did figure out the

difference.

When I finish my story, dearie, I'll teach you Orsemay. I've been

beamed that you've enough prestige to join our Highest Hill sorority

and thus learn our secret communication.

Mother declared Father had two means of pulsing. Besides his radio,

which he used to communicate with us, he could pulse in another and

totally different manner. He didn't use dotdeet-ditdashes, either. His

pulses needed air to carry them, and he sent them with the same organ

he ate with. Boils one's stomach to think of it, doesn't it?

Father was caught while passing by my Mother. She didn't know what

mating-lust perfume to send downwind towards him so he would be

lured within reach of her tentacles. She had never smelled a mobile

like him before. But he did have an odor that was similar to that of

another kind of mobile, so she wafted that towards him. It seemed

to work, because he came close enough for her to seize him with her

extra-uterine tentacles and pop him into her shell.

Later, after I was born, Father radioed me—in Orsemay, of course,

so Mother wouldn't understand—that he had smelled the perfume and

that it, among other things, had attracted him. But the odor had been

that of a hairy tree-climbing mobile, and he had wondered what such

creatures were doing on a bare hill-top. When he learned to converse

with Mother, he was surprised that she had identified him with that

mobile.

Ah, well, he pulsed, it is not the first time a female has made a

monkey of a man.

He also informed me that he had thought Mother was just an enormous

boulder on top of the hill. Not until a section of the supposed rock

opened out was he aware of anything out of the ordinary or that the

boulder was her shell and held her body within. Mother, he radioed,

is something like a dinosaur-sized snail, or jellyfish, equipped with

organs that generate radar and radio waves and with an egg-shaped

chamber big as the living room of a bungalow, a womb in which she bears

and raises her young.

I didn't understand more than half of these terms of course. Nor was

Father able to explain them satisfactorily.

He did make me promise not to pulse Mother that he had thought she was

just a big lump of mineral. Why, I don't know.

Father puzzled Mother. Though he fought her when she dragged him in,

he had no claws or teeth sharp enough to tear her conception-spot.

Mother tried to provoke him further, but he refused to react. When

she realized that he was a pulse-sending mobile, and released him to

study him, he wandered around the womb. After a while he caught on to

the fact that Mother was beaming from her womb pulse-stalk. He learned

how to talk with her by using his detachable organ, which he termed

a panrad. Eventually, he taught her his language, mobile-pulse. When

Mother learned that and informed other Mothers about that, her prestige

became the highest in all the area. No Mother had ever thought of a new

language. The idea stunned them.

Father said he was the only communicating mobile on this world. His

s-p-a-c-e-s-h-i-p had crashed, and he would now remain forever with

Mother.

Father learned the dinnerpulses when Mother summoned her young playing

about her womb. He radioed the proper message. Mother's nerves were

quivered by the idea that he was semantic, but she opened her stew-iris

and let him eat. Then Father held up fruit or other objects and let

Mother beam at him with her wombstalk what the proper dotdit-deetdashes

were for each. Then he would repeat on his panrad the name of the

object to verify it.

Mother's sense of smell helped her, of course. Sometimes, it is hard to

tell the difference between an apple and a peach just by pulsing it.

Odors aid you.

She caught on fast. Father told her she was very intelligent—for a

female. That quivered her nerves. She wouldn't pulse with him for

several mealperiods after that.

One thing that Mother especially liked about Father was that when

conception-time came, she could direct him what to do. She didn't have

to depend on luring a non-semantic mobile into her shell with perfumes

and then hold it to her conception-spot while it scratched and bit the

spot in its efforts to fight its way from the grip of her tentacles.

Father had no claws, but he carried a detachable claw. He named it an

s-c-a-l-p-e-l.

When I asked him why he had so many detachable organs, he replied that

he was a man of parts.

Father was always talking nonsense.

But he had trouble understanding Mother, too.

Her reproductive processes amazed him.

"By G-o-d," he beamed, "who'd believe it? That a healing process in a

wound would result in conception? Just the opposite of cancer."

When we were adolescents and about ready to be shoved out of Mother's

shell, we received Mother asking Father to mangle her spot again.

Father replied no. He wanted to wait another four seasons. He had said

farewell to two broods of his young, and he wanted to keep us around

longer so he could give us a real education and enjoy us instead of

starting to raise another group of virgins.

This refusal quivered Mother's nerves and upset her stew-stomach so

that our food was sour for several meals. But she didn't act against

him. He gave her too much prestige. All the Mothers were dropping

Motherpulse and learning mobile from Mother as fast as she could teach

it.

I asked, "What's prestige?"

"When you send, the others have to receive. And they don't dare pulse

back until you're through and you give your permission."

"Oh, I'd like prestige!"

Father interrupted, "Little Hardhead, if you want to get ahead, you

tune in to me. I'll tell you a few things even your Mother can't. After

all, I'm a mobile, and I've been around."

And he would outline what I had to expect once I left him and Mother

and how, if I used my brain, I could survive and eventually get more

prestige than even Grandmother had.

Why he called me Hardhead, I don't know. I was still a virgin and

had not, of course, grown a shell. I was as soft-bodied as any of

my sisters. But he told me he was f-o-n-d of me because I was so

hard-headed. I accepted the statement without trying to grasp it.

Anyway, we got eight extra seasons in Mother because Father wanted it

that way. We might have gotten some more, but when winter came again,

Mother insisted Father mangle her spot. He replied he wasn't ready. He

was just beginning to get acquainted with his children—he called us

Sluggos—and, after we left, he'd have nobody but Mother to talk to

until the next brood grew up.

Moreover, she was starting to repeat herself and he didn't think she

appreciated him like she should. Her stew was too often soured or else

so over-boiled that the meat was shredded into a neargoo.

That was enough for Mother.

"Get out!" she pulsed.

"Fine! And don't think you're throwing me out in the cold, either!"

zztd back Father. "Yours is not the only shell in this world."

That made Mother's nerves quiver until her whole body shook. She put

up her big outside stalk and beamed her sisters and aunts. The Mother

across the valley confessed that, during one of the times Father had

basked in the warmth of the s-u-n while lying just outside Mother's

opened iris, she had asked him to come live with her.

Mother changed her mind. She realized that, with him gone, her prestige

would die and that of the hussy across the valley would grow.

"Seems as if I'm here for the duration," radioed Father.

Then, "Whoever would think your Mother'd be j-e-a-l-o-u-s?"

Life with Father was full of those incomprehensible semantic groups.

Too often he would not, or could not, explain.

For a long time Father brooded in one spot. He wouldn't answer us or

Mother.

Finally, she became overquivered. We had grown so big and boisterous

and sassy that she was one continual shudder. And she must have thought

that as long as we were around to communicate with him, she had no

chance to get him to rip up her spot.

So, out we went.

Before we passed forever from her shell, she warned, "Beware the

olfway."

My sisters ignored her, but I was impressed. Father had described the

beast and its terrible ways. Indeed, he used to dwell so much on it

that we young, and Mother, had dropped the old term for it and used

Father's. It began when he reprimanded her for threatening us too often

with the beast when we misbehaved.

"Don't 'cry wolf.'"

He then beamed me the story of the origin of that puzzling phrase. He

did it in Orsemay, of course, because Mother would lash him with her

tentacles if she thought he was pulsing something that was not-so.

The very idea of not-so strained her brain until she couldn't think

straight.

I wasn't sure myself what not-so was, but I enjoyed his stories. And

I, like the other virgins and Mother herself, began terming the killer

"the olfway."

Anyway, after I'd beamed, "Good sending, Mother," I felt Father's

strange stiff mobile-tentacles around me and something wet and warm

falling from him onto me. He pulsed, "Good l-u-c-k, Hardhead. Send me a

message via hook-up sometimes. And be sure to remember what I told you

about dealing with the olfway."

I pulsed that I would. I left with the most indescribable feeling

inside me. It was a nervequivering that was both good and bad, if you

can imagine such a thing, dearie.

But I soon forgot it in the adventure of rolling down a hill, climbing

slowly up the next one on my single foot, rolling down the other side,

and so on. After about ten warm-periods, all my sisters but two had

left me. They found hilltops on which to build their shells. But my two

faithful sisters had listened to my ideas about how we should not be

content with anything less than the highest hilltops.

"Once you've grown a shell, you stay where you are."

So they agreed to follow me.

But I led them a long, long ways, and they would complain that they

were tired and sore and getting afraid of running into some meat-eating

mobile. They even wanted to move into the empty shells of Mothers who

had been eaten by the olfway or died when cancer, instead of young,

developed in the conception-spots.

"Come on," I urged. "There's no prestige in moving into empties. Do

you want to take bottom place in every community-pulsing just because

you're too lazy to build your own covers?"

"But we'll resorb the empties and then grow our own later on."

"Yes? How many Mothers have declared that? And how many have done it?

Come on, Sluggos."

We kept getting into higher country. Finally, I scanned the set-up I

was searching for. It was a small, flat-topped mountain with many hills

around it. I crept up it. When I was on top, I test-beamed. Its summit

was higher than any of the eminences for as far as I could reach. And

I guessed that when I became adult and had much more power, I would be

able to cover a tremendous area. Meanwhile, other virgins would sooner

or later be moving in and occupying the lesser hills.

As Father would have expressed it, I was on top of the world.

It happened that my little mountain was rich. The search-tendrils I

grew and then sunk into the soil found many varieties of minerals. I

could build from them a huge shell. The bigger the shell, the larger

the Mother. The larger the Mother, the more powerful the pulse.

Moreover, I detected many large flying mobiles. Eagles, Father termed

them. They would make good mates. They had sharp beaks and tearing

talons.

Below, in a valley, was a stream. I grew a hollow-tendril under the

soil and down the mountainside until it entered the water. Then I began

pumping it up to fill my stomachs.

The valley soil was good. I did what no other of our kind had ever

done, what Father had taught me. My far-groping tendrils picked up

seeds dropped by trees or flowers or birds and planted them. I spread

an underground net of tendrils around an apple tree. But I didn't plan

on passing the tree's fallen fruit from tendril-frond to frond and so

on up the slope and into my irises. I had a different destination in

mind for them.

Meanwhile, my sisters had topped two hills much lower than mine. When

I found out what they were doing, my nerves quivered. Both had built

shells! One was glass; the other, cellulose!

"What do you think you're doing? Aren't you afraid of the olfway?"

"Pulse away, old grouch. Nothing's the matter with us. We're just ready

for winter and mating-heat, that's all. We'll be Mothers, then, and

you'll still be growing your big old shell. Where'll your prestige be?

The others won't even pulse with you 'cause you'll still be a virgin

and a half-shelled one at that!"

"Brittlehead! Woodenhead!"

"Yah! Yah! Hardhead!"

They were right—in a way. I was still soft and naked and helpless, an

evergrowing mass of quivering flesh, a ready prey to any meat-eating

mobile that found me. I was a fool and a gambler. Nevertheless, I

took my leisure and sunk my tendrils and located ore and sucked up

iron in suspension and built an inner shell larger, I think, than

Grandmother's. Then I laid a thick sheath of copper over that, so

the iron wouldn't rust. Over that I grew a layer of bone made out of

calcium I'd extracted from the rocks thereabouts. Nor did I bother, as

my sisters had done, to resorb my virgin's stalk and grow an adult one.

That could come later.

Just as fall was going out, I finished my shells. Body-changing and

growing began. I ate from my crops, and I had much meat, too, because

I'd put up little cellulose latticework shells in the valley and raised

many mobiles from the young that my far-groping tendrils had plucked

from their nests.

I planned my structure with an end in mind. I grew my stomach much

broader and deeper than usual. It was not that I was overly hungry. It

was for a purpose, which I shall transmit to you later, dearie.

My stew-stomach was also much closer to the top of my shell than it is

in most of us. In fact, I intentionally shifted my brain from the top

to one side and raised the stomach in its place. Father had informed me

I should take advantage of my ability to partially direct the location

of my adult organs. It took me time, but I did it just before winter

came.

Cold weather arrived.

And the olfway.

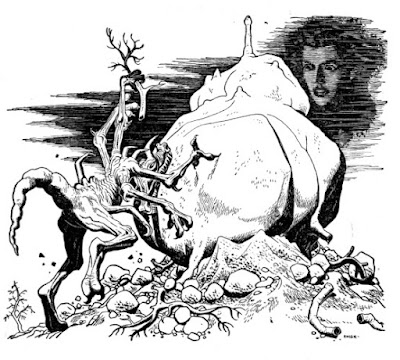

He came as he always does, his long nose with its retractible antennae

sniffing out the minute encrustations of pure minerals that we virgins

leave on our trails. The olfway follows his nose to wherever it will

take him. This time it led him to my sister who had built her shell of

glass. I had suspected she would be the first to be contacted by an

olfway. In fact, that was one of the reasons I had chosen a hill-top

further down the line. The olfway always takes the closest shell.

When sister Glasshead detected the terrible mobile, she sent out wild

pulse after pulse.

"What will I do? Do? Do?"

"Sit tight, sister, and hope."

Such advice was like feeding on cold stew, but it was the best, and

the only, that I could give. I did not remind her that she should have

followed my example, built a triple shell, and not been so eager to

have a good time by gossiping with others.

The olfway prowled about, tried to dig underneath her base, which was

on solid rock, and failed. He did manage to knock off a chunk of glass

as a sample. Ordinarily, he would then have swallowed the sample and

gone off to pupate. That would have given my sister a season of rest

before he returned to attack. In the meanwhile, she might have built

another coating of some other material and frustrated the monster for

another season.

It just so happened that that particular olfway had, unfortunately for

sister, made his last meal on a Mother whose covering had also been of

glass. He retained his special organs for dealing with such mixtures of

silicates. One of them was a huge and hard ball of some material on the

end of his very long tail. Another was an acid for weakening the glass.

After he had dripped that over a certain area, he battered her shell

with the ball. Not long before the first snowfall he broke through her

shield and got to her flesh.

Her wildly alternating beams and broadcasts of panic and terror still

bounce around in my nerves when I think of them. Yet, I must admit my

reaction was tinged with contempt. I do not think she had even taken

the trouble to put boron oxide instead of silicon in her glass. If she

had, she might....

What's that? How dare you interrupt?... Oh, very well, I accept your

humble apologies. Don't let it happen again, dearie. As for what you

wanted to know, I'll describe later the substances that Father termed

silicates and boron oxides and such. After my story is done.

To continue, the killer, after finishing Glasshead off, followed his

nose along her trail back down the hill to the junction. There he had

his choice of my other sister's or of mine. He decided on hers. Again

he went through his pattern of trying to dig under her, crawling over

her, biting off her pulse-stalks, and then chewing a sample of shell.

Snow fell hard. He crept off, sluggishly scooped a hole, and crawled in

for the winter.

Sister Woodenhead grew another stalk. She exulted, "He found my shell

too thick! He'll never get me!"

Ah, sister, if only you had received from Father and not spent so much

time playing with the other Sluggos. Then you would have remembered

what he taught. You would have known that an olfway, like us, is

different from most creatures. The majority of beings have functions

that depend upon their structures. But the olfway, that nasty creature,

has a structure that depends upon his functions.

I did not quiver her nerves by telling her that, now that he had

secreted a sample of her cellulose-shell in his body, he was pupating

around it. Father had informed me that some arthropods follow a

life-stage that goes from egg to larva to pupa to adult. When a

caterpillar pupates in its cocoon, for instance, practically its whole

body dissolves, its tissues disintegrate. Then something reforms the

pulpy whole into a structurally new creature with new functions, the

butterfly.

The butterfly, however, never repupates. The olfway does. He parts

company with his fellow arthropods in this peculiar ability. Thus,

when he tackles a Mother, he chews off a tiny bit of the shell and

goes to sleep with it. During a whole season, crouched in his den, he

dreams around the sample—or his body does. His tissues melt and then

coalesce. Only his nervous system remains intact, thus preserving the

memory of his identity and what he has to do when he emerges from his

hole.

So it happened. The olfway came out of his hole, nested on top of

sister Woodenhead's dome, and inserted a modified ovipositor into the

hole left by again biting off her stalk. I could more or less follow

his plan of attack, because the winds quite often blew my way, and I

could sniff the chemicals he was dripping.

He pulped the cellulose with a solution of something or other, soaked

it in some caustic stuff, and then poured on an evil-smelling fluid

that boiled and bubbled. After that had ceased its violent action,

he washed some more caustic on the enlarging depression and finished

by blowing out the viscous solution through a tube. He repeated the

process many times.

Though my sister, I suppose, desperately grew more cellulose, she was

not fast enough. Relentlessly, the olfway widened the hole. When it was

large enough, he slipped inside.

End of sister....

The whole affair of the olfway was lengthy. I was busy, and I gained

time by something I had made even before I erected my dome. This was

the false trail of encrustations that I had laid, one of the very

things my sisters had mocked. They did not understand what I was doing

when I then back-tracked, a process which took me several days, and

concealed with dirt my real track. But if they had lived, they would

have comprehended. For the olfway turned off the genuine trail to my

summit and followed the false.

Naturally, it led him to the edge of a cliff. Before he could check his

swift pace, he fell off.

Somehow, he escaped serious injury and scrambled back up to the

spurious path. Reversing, he found and dug up the cover over the actual

tracks.

That counterfeit path was a good trick, one my Father taught me. Too

bad it hadn't worked, for the monster came straight up the mountain,

heading for me, his antennae plowing up the loose dirt and branches

which covered my encrustations.

However, I wasn't through. Long before he showed up I had collected a

number of large rocks and cemented them into one large boulder. The

boulder itself was poised on the edge of the summit. Around its middle

I had deposited a ring of iron, grooved to fit a rail of the same

mineral. This rail led from the boulder to a point halfway down the

slope. Thus, when the mobile had reached that ridge of iron and was

following it up the slope, I removed with my tentacles the little rocks

that kept the boulder from toppling over the edge of the summit.

My weapon rolled down its track with terrific speed. I'm sure it would

have crushed the olfway if he had not felt the rail vibrating with his

nose. He sprawled aside. The boulder rushed by, just missing him.

Though disappointed, I did get another idea to deal with future

olfways. If I deposited two rails halfway down the slope, one on each

side of the main line, and sent three boulders down at the same time,

the monster could leap aside from the center, either way, and still get

it on the nose!

He must have been frightened, for I didn't pip him for five

warm-periods after that. Then he came back up the rail, not, as I had

expected, up the opposite if much steeper side of the mountain. He was

stupid, all right.

I want to pause here and explain that the boulder was my idea, not

Father's. Yet I must add that it was Father, not Mother, who started me

thinking original thoughts. I know it quivers all your nerves to think

that a mere mobile, good for nothing but food and mating, could not

only be semantic but could have a higher degree of semanticism.

I don't insist he had a higher quality. I think it was different, and

that I got some of that difference from him.

To continue, there was nothing I could do while the olfway prowled

about and sampled my shell. Nothing except hope. And hope, as I found

out, isn't enough. The mobile bit off a piece of my shell's outer bone

covering. I thought he'd be satisfied, and that, when he returned after

pupating, he'd find the second sheath of copper. That would delay him

until another season. Then he'd find the iron and have to retire again.

By then it would be winter, and he'd be forced to hibernate or else he

would be so frustrated he'd give up and go searching for easier prey.

I didn't know that an olfway never gives up and is very thorough. He

spent days digging around my base and uncovered a place where I'd

been careless in sheathing. All three elements of the shell could be

detected. I knew the weak spot existed, but I hadn't thought he'd go

that deep.

Away went the killer to pupate. When summer came, he crawled out of

his hole. Before attacking me, however, he ate up my crops, upset my

cage-shells and devoured the mobiles therein, dug up my tendrils and

ate them, and broke off my waterpipe.

But when he picked all the apples off my tree and consumed them,

my nerves tingled. The summer before I had transported, via my

network of underground tendrils, an amount of a certain poisonous

mineral to the tree. In so doing I killed the tendrils that did the

work, but I succeeded in feeding to the roots minute amounts of the

stuff—selenium, Father termed it, I think. I grew more tendrils and

carried more poison to the tree. Eventually, the plant was full of

the potion, yet I had fed it so slowly that it had built up a kind of

immunity. A kind of, I say, because it was actually a rather sickly

tree.

I must admit I got the idea from one of Father's not-so stories, tapped

out in Orsemay so Mother wouldn't be vexed. It was about a mobile—a

female, Father claimed, though I find the concept of a female mobile

too nervequivering to dwell on—a mobile who was put into a long sleep

by a poisoned apple.

The olfway seemed not to have heard of the story. All he did was retch.

After he had recovered, he crawled up and perched on top of my dome. He

broke off my big pulse-stalk and inserted his ovipositor in the hole

and began dripping acid.

I was frightened, true, for as you all know, there is nothing more

panic-striking than being deprived of pulsing and not knowing at all

what is going on in the world outside your shell. But, at the same

time, his actions were what I had expected and planned on. So I tried

to suppress my nervequiverings. After all, I knew the olfway would work

on that spot. It was for that very reason that I had shifted my brain

to one side and jacked up my oversize stomach closer to the top of my

dome.

My sisters had scoffed because I'd taken so much trouble with my

organs. They'd been satisfied with the normal procedure of growing into

Mother-size. While I was still waiting for the water pumped up from

the stream to fill my sac, my sisters had long before heated theirs

and were eating nice warm stew. Meanwhile, I was consuming much fruit

and uncooked meat, which sometimes made me sick. However, the rejected

stuff was good for the crops, so I didn't altogether suffer a loss.

As you know, once the stomach is full of water and well walled up, our

body heat warms the fluid. As there is no leakage of heat except when

we iris meat and vegetables in or out, the water comes to the boiling

point.

Well, to pulse on with the story, when the mobile had scaled away the

bone and copper and iron with his acids and made a hole large enough

for his body, he dropped in for dinner.

I suppose he anticipated the usual helpless Mother or virgin, nerves

numbed and waiting to be eaten.

If he did, his own nerves must have quivered. There was an iris on the

upper part of my stomach, and it had been grown with the dimensions of

a certain carnivorous mobile in mind.

But there was a period when I thought I hadn't fashioned the opening

large enough. I had him half through, but I couldn't get his

hindquarters past the lips. He was wedged in tight and clawing my

flesh away in great gobbets. I was in such pain I shook my body back

and forth and, I believe, actually rocked my shell on its base. Yet,

despite my jerking nerves, I strained and struggled and gulped hard,

oh, so hard. And, finally, just when I was on the verge of vomiting him

back up the hole through which he had come, which would have been the

end of me, I gave a tremendous convulsive gulp and popped him in.

My iris closed. Nor, much as he bit and poured out searing acids,

would I open it again. I was determined that I was going to keep this

meat in my stew, the biggest piece any Mother had ever had.

Oh, he fought. But not for long. The boiling water pushed into his open

mouth and drenched his breathing-sacs. He couldn't take a sample of

that hot fluid and then crawl off to pupate around it.

He was through—and he was delicious.

Yes, I know that I am to be congratulated and that this information

for dealing with the monster must be broadcast to every one of us

everywhere. But don't forget to pulse that a mobile was partly

responsible for the victory over our ancient enemy. It may quiver your

nerves to admit it, but he was.

Where did I get the idea of putting my stew-sac just below the hole the

olfway always makes in the top of our shells? Well, it was like so many

I had. It came from one of Father's not-so stories, told in Orsemay.

I'll pulse it sometime when I'm not so busy. After you, dearie, have

learned our secret language.

I'll start your lessons now. First....

What's that? You're quivering with curiosity? Oh, very well, I'll give

you some idea of the not-so story, then I'll continue my lessons with

this neophyte.

It's about eethay olfway and eethay eethray ittlelay igspay.

Philip José Farmer @ Amazon

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)