By GEORGE O. SMITH

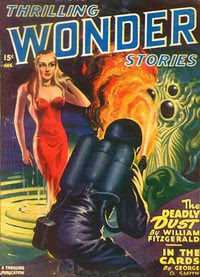

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Thrilling Wonder Stories, April 1947.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER I

Soft Assignment

Captain Alfred Weston entered the room and nodded curtly to the men at the conference table. Doctor Edwards, holding forth at the head of the table, nodded as though he had not seen the over-polite greeting. He waved the newcomer to an empty seat on the opposite side of the table, and Weston went around to sit down.

Edwards had been talking on some other subject, obviously, but now he dropped it. "Captain Weston," he said, "you are still classified as convalescent."

"Rank foolishness," grumbled Weston.

"Unfortunately," smiled Edwards, "it is the Medical Corps that makes the decision. A bit of rest does no man any harm. But, Weston, despite the convalescent classification, we have a job that seems to be right up your alley. Want it?"

"You're asking?" said Weston quizzically. "This is no order?"

"As an official convalescent, we cannot order you to duty."

Weston scowled. "I see no choice," he said. His tone was surly, his whole attitude inimical.

"Nevertheless, the choice is your own," said Edwards. As psychiatrist for the Medical Corps, Edwards was treading on thin ground. But he knew he must force this disagreement into the open and blast it out of Weston's mind.

It was a common enough block, but it needed elimination.

"Certainly the choice is mine," said Weston bitterly. "Hobson's Choice. Either I take the job and do it, or I refuse to take it and gain the disrespect of the entire Corps. I see no choice and therefore I will take your job—sight unseen!"

"We shall offer the job," said Edwards flatly. "After which you will make your decision."

"Very well," answered Weston sullenly.

Edwards ignored the tone of the answer. "Weston, you are a ranking officer. This job requires a ranking officer because it demands someone whose authority to investigate will not be questioned, scoffed at or ignored. You are now a Captain. We intend to raise your rank to Senior Captain—which is due you and has been withheld only until your convalescence is complete.

"We shall offer you a roving order and a four-mark commissioned directive which will give you authority to requisition whatever items you may need to complete your project. Experimental Spacecraft Number XXII will be assigned to you."

"You make it very attractive. Shall I now quote the ancient one about 'Beware of Greeks bearing gifts'?"

"There is no need for insolence, Weston. You are in excellent position to do us a service. If you accept it will not be necessary to create a hole in the Corps by removing some other ranking officer from his command. This job will also give you the swing of space once again. You've been out of space now for about a year—"

"Ever since the First Directive attack," said Weston bitterly.

"Right. But look, Weston. Regardless of what opinion the world may have, we in this room have reason to believe that there is something hidden behind the Jordan Green legend. We want you to get to the bottom of it. Will you do this?"

Weston grunted. He looked across the room to the door beside the blank wall beside the doorframe. On the space above the chair-rail were the scrawled words Jordan Green was here!

They were written in space-chart chalk, which Weston understood to be the case with the uncounted thousands of such scrawlings sprinkled all over the Solar System. It looked like a hurried scrawl at first glance, yet it could not have been written by a man in a tearing hurry because it was so very legible.

Weston himself had seen over a thousand of such scrawls in out of the way places and he had joined in the hours of discussion that went on through the Space Corps as to who Jordan Green might be, and if there were really such a character.

Jordan Green, it seemed, was one of those legendary people that are never seen. He had been everywhere and had apparently been there first. It was a common joke that, if the Space Corps started to erect a lonely outpost on some secret asteroid on Monday, Tuesday morning would find Jordan Green's familiar scrawl beside the door on the unfinished wall.

The trouble was that Weston himself had written one or two of these messages. And though he suspected that every officer in the Corps had been guilty of perpetuating the gag at some time or other, not one of them ever admitted it. It was a sort of unmentioned, no-prize contest in the Corps just something to talk about in the long lonely times between missions.

Every officer clamored for missions to the out of the way places because he hoped to have a Jordan Green yarn to spin and the legendary traveller was always reported. Weston smiled at one incident he had heard of.

An officer he knew had found a place where there was no scrawl and had written, I beat Jordan Green to this spot! The following day there was written beneath it, So what? Have you looked under the wallpaper? Jordan Green. The officer had torn away the wallpaper and, below it on the bare plaster, was the original scrawl.

The officer was still living down the joke.

None the less Weston thought it a waste of time to send a ranking officer on such a wild-goose chase.

He said so. And he went on to recount the facts of the case as he knew them. How, he wanted to know, was he to proceed when he was almost certain that every man in the Space Corps was guilty?

Edwards listened to Weston's objections. He agreed, partially.

"It is admitted that the officers may have amused themselves by writing it themselves. But when you consider the man-hours and the kilowatts wasted in space-chatter the Martian War could have been finished in three months less time.

"The problem is just this, Weston. Did it start as a joke—perhaps like the boy who carves his initials the highest in the Old Oak Tree—or was some agency hoping to cause enough waste to slow up our prosecution of the late war?"

"I believe that it was started by some courier," said Weston flatly. "Then it caught on and pyramided far beyond Jordan Green's expectations. Have you sought the man himself?"

"We've established that any Jordan Greens in the service were not responsible," said Edwards. "However, this possible courier of yours probably would take a pseudonym lest fooling around with official time and energy get him a reprimand. We want you to track down the origin of Jordan Green! Will you do it?"

Weston shrugged. "I have no choice."

Edwards turned to the man beside him. "Commodore Atkins, will you provide Senior Captain Weston with the necessary credentials, papers, orders and insignia?"

Atkins smiled. "Come to my office, Weston. We'll have you fixed up in a hurry."

Weston rose and followed the commodore out of the room. Then Edwards turned to the other doctor in the conference room and took a deep breath before he said: "Well, that much is accomplished!"

"You're the psychiatrist," said the other. "I'm just a simple surgeon. For the life of me, I can't see it. What happens when Weston discovers that this is just a peg-whittling job handed out to a good man who is going stale for lack of something to do?"

"Reconsider his case from the psychiatric angle," said Edwards. "Weston was an excellent officer. Because of his record he was one of twenty men selected to carry the first projectors of Directive Power against Mars. He was proud of being included in the Directive Power attack.

"His position in the task force was one that gave him the highest statistical chance for success—yet with the usual trick of fate, Weston was the first and only man whose ship was shot to pieces in the counter-measure defense. He never even warmed up the secondary feeds to the Directive Power system before he was hit.

"The rescue squadron picked him up in bad shape. He was maintained in artificial unconsciousness while you put him together again—but by that time the Martians had surrendered and the war was over. Weston feels that he missed his big chance to go down in history. It's a plain case of frustration and self-guilt."

"But how can sending him on this wild-goose chase do any good?"

"The cure for frustration is to let the subject either do that which he has been barred from doing, or to give him something as pleasing to do to divert his attention. The way to cure the type of self-guilt that Weston has—an inner feeling of failure—is to give him something in which he can succeed."

"But—"

"However, we cannot start another war. Aside from our natural reluctance, we'd have first to develop the application of Directive Power to the space drive, which will give us interstellar flight, and we'd have to go out in the galaxy with a chip on our shoulder to seek such a war.

"Then Weston might be able to obtain release. He is like the chap whose classmate turns up a Space Admiral while he himself is mustered out of service because of Venusite malaria.

"However niggling this job may be, by the time that Weston is cured through the work he'll be doing he will note that all of his former friends are envious of the very lush job he has.

"All space-hopping, no fixed base, a roving commission at four-mark level, an experimental spacecraft and, because he is chasing a will of the wisp that may be either malignant or downright foolish, no one will question his actions, castigate him if he fails or scorn his job.

"Remember this, Tomlinson, any man who goes out to unwind a wildly-tangled legend to its core has a real job on his hands. There must be reams and reams of conflicting evidence that will itself cover up our little work-therapy until he gets interested in some outlandish phase of it and settles down to work. Once he readjusts he won't mind a bit. Right now, however, Weston is mingled anger and gratification."

"Why?"

"He is happy because of the commission and the increase in rank and the freedom of action. He is angry, Tomlinson, because he knows that we have confidence in him. His self-pity is blasted because we still think he is a good bet.

"To continue in his present mental state requires that he continue to believe himself battered by fate. In other words, to enjoy his frustration-complex Weston must continue to be frustrated."

"Golly!" breathed Tomlinson. "Even when a man is slightly nuts he likes himself that way!"

"Correct," laughed Edwards. "That's one of the things that makes psychiatry difficult. It also makes Weston hate any condition which forces him to change. Now, to space with Al Weston. I'm hungry. How about you?"

Tomlinson grinned, nodded and beat Doctor Edwards to the door.

CHAPTER II

No Coddling, Please

Senior Captain Alfred Weston sat in his experimental spacecraft and wondered about it all. He had a swamped, shut-in feeling that was growing worse as the hours went by. He knew that he would never have another chance as good as his first chance with the Directive Power attack. In that he had failed.

This job was a fool project at best. Weston had come down from one of twenty selected men to a high-priced office boy's position. Not that he objected to regaining his position in the eyes of the world via some honest project—but if they persisted in bringing him back along the long hard road, it would be so very long and so very hard.

After all, he was no ensign, to rise through the ranks gaining experience. Yet that is what he was going to do—again. There had to be some project worthy of his ability!

There was conflict in his mind. One very small portion of his brain kept telling him that they did not hand out four-mark commissions, increases in rank and roving orders to ensigns, even ensigns in fact with captain's ratings.

He scoffed at that, but was forced to recognize it anyway. In a fit of sarcasm he went to the wall beside the spacelock, grabbed a piece of space-chart chalk and scrawled, Jordan Green was here, too! on the wall.

Then he threw the chalk out the spacelock door in a fit of temper.

The whole assignment was far beneath his dignity. An officer of his rank should have a large command, not a small speedster—even one of the desirable experimental models. He felt like a President of the Interplanetary Communications Network, forced to replace worn patch-cords in a telephone exchange, or a President of Terra, forced to write official letters to a number of third-class civil service employees.

He, Alfred Weston, was being forced to forego his command in order to snoop around trying to locate the originator of one of the craziest space-gags in history.

Well, so it was beneath his notice—he could treat it with proper disdain. No doubt the President of ICN might enjoy replacing worn out patch-cords just to keep his hand in. He could do the same. He could make whatever stupid moves were necessary, make them with an air of superiority that made it obvious he was not extending himself. He might appear to even be doing it for the laughs.

Laughs! he thought. People will think that's all I'm to be trusted with!

He shrugged. He was on a roving commission, and therefore there was no one to watch his progress. He'd put others to work and loaf.

He snapped the communicator, dialed the Department for official orders, gave his rank and commission, issued a blanket order directed at the commanders at all Terran Posts.

"Compile a cross-indexed list of all Jordan Green markings in your command-posts. The listings must be complete on the following factors: text, writing material, handwriting index and approximate location."

This, he knew, would take time. Perhaps he would be forced to follow up the original order with a more firm request. Weston expected no results immediately.

But the mass of data that came pouring in staggered him. It mounted high, it was complex and uncorrelated. Weston's natural dislike of the project made him lax in his work. He went at it in desultory fashion, which resulted in his getting far behind any schedule. The work continued to pile up and ultimately snowed him under.

He began to hate the sight of his desk as the days went by and avoided it diligently. It was groaning under the pile of paperwork. Instead of using his ability and freedom to dig into the job, Weston used his commission and his rank to enter places formerly forbidden to him.

On the pretense of seeking Jordan Green information, he entered the ultra-secret space laboratory on Luna and watched work on highly restricted technical developments. He was especially interested in the work of adapting Directive Power to the space drive and, because they knew him and of him, the scientists were quite free with information that might have been withheld from any visitor of rank lower than Senior Captain.

This he enjoyed. It was a privilege given to all officers of senior rank, a type of compensation, a relaxation. That he accepted the offer without doing his job was unimportant to Weston. He felt that they owed it to him.

By the time he returned from Luna, he had more data that he merely tossed on the pile—and it was immediately covered by another pile of data that had come in during his absence and was awaiting his return. He decided he was too far behind ever to catch up, and so he loafed in the scanning room, looking at the pile of work with a disconnected view as though it were not his.

His loafing was not affected by the streams of favorable publicity he received. His picture was used occasionally; he was mentioned frequently in commendation. It was well-known that the only casualty from the First Directive Attack was working through his convalescence on the very complex job of uncovering the source of the Jordan Green legend.

But Weston knew just how important his job really was, and he ignored both it and the glowing reports of the newspapers.

Eventually friends caught up with him and demanded that he come along on a party. He tried to wriggle out of it, but they insisted. Their intention of making him enjoy himself was obvious. He viewed them with a certain amount of scorn, though he said nothing about it.

If it gave them pleasure to try to lift him out of his slough of despond he'd not stop them, but he could avoid them and their silly prattlings. They would not be denied, however, so Al Weston went, reluctantly.

Obviously for his benefit, someone had scrawled Jordan Green was here! on the side of the wall in Jeanne Tarbell's home, and as he entered the whole gang was discussing it. They turned to him for an official opinion.

"Most of them were made the way this one was," he said scornfully.

Tony Larkin laughed. He turned to Jeanne.

"You see," he said, "a lot of us had much to do with winning the war. I've—found several—myself."

"Scrawled several," corrected Weston sourly.

"Don't be bitter," said Larkin. "Even though you now outrank me, you shouldn't change from boyish prank to official pomp overnight."

"Maybe you'd like to have as silly a job hung on you," snapped Weston.

"If the commish and the roving order and all went with it—I'd take to it like a duck to water."

"Is that all you're good for?" asked Weston scornfully.

"Look, Al, I'm a plain captain in this man's Space Corps," returned Larkin. "Anytime I want to sweep up the floor in my office I'll do it, see? One—no one can do it better, and two—no one can say that sweeping floors is my top position in life.

"It isn't a loss of dignity to exhibit your skill in ditch-digging or muck-raking. It makes you more human when people know that, despite your gold braid, you aren't afraid to get your hands as dirty as theirs. At least they didn't plant you in the front office because you'd make a mess of working in the machine shop."

"You'd not like to be ordered to a dirty job," snapped Weston.

"If it had to be done and I was told to do it, I'd do it and do it quick. You can take a bath afterwards and wash off the dirt—and be the gainer for knowing how the Other Half lives!"

Weston turned and walked out. Larkin frowned sorrowfully and apologized to Jeanne and the rest. Tom Brandt shrugged.

"We all agree, Tony," he said. "But drumming at him will do no good. He'll have to find himself on his own time."

Jeanne nodded and went out after Weston.

"Al," she said, pleading, "come back and be the man we used to know."

"I can't," he said. He was utterly dejected.

"But you can. It's in you. Apply yourself. So this is a poor job in your estimation. If it is beneath your ability you should be able to do it with one hand."

"You too?" he said bitterly. "I thought you'd see things my way."

"I do, honestly. But, Al, I can't turn back the clock. I can't give you another chance at the Directive thing. You did not fail. No one thinks you did or they'd not trust you with a high rank and a free commission. You were the victim of sheer chance and none of it was your fault."

"But why did it happen to me?" he cried bitterly. "Why couldn't I have been successful?"

"Someone was bound to get it," she said simply. "You prefer your own skin to someone else's?"

"Wouldn't you—if the chips were down?"

She nodded. "Certainly. But I don't think I'd hate everybody that was successful if I were the unlucky one."

"Then they top it off by giving me this stupid job."

"Maybe you think that unraveling a legend is child's play. Well, Alfred Weston, satisfying the demands or the interest of a few billion people as to the truth of Jordan Green is no small item!

"He who satisfies the public interest is far more admired than a captain of industry or a ruler of people. And if this job is a boy's work why did they send a man to do it, complete with increase in rank and a roving commission?"

"Because Jordan Green was of no importance until they needed a simple job to use in coddling a man they consider a simpleton!" growled Weston.

"And you are the man they selected to join with the Directive Power attack," she said, stepping back and inspecting him carefully. "Well, suppose you complete this simple job first. Then let's see whether you can accomplish something you consider worthy of your stature."

"You're insulting," he said shortly.

"You wouldn't be able to recognize an insult," she said scornfully. She turned and left the place with tears in her eyes. Tony Larkin intercepted her and dried her eyes.

"It's tough," he told her. "But until he shakes the feeling that Fate is against him he'll be poor company. Eventually everybody will dislike him and then he'll have nothing to do but to go ahead and work.

"Whatever initial success comes will break his interest in himself. He'll go at it in desperation, in hatred perhaps, but he'll emerge with a sense of humor again. Until then, Jeanne, you'll have to sit and suffer with the rest of us."

"But was that Jordan Green job wise?"

"I can think of a thousand officers who would tackle it with shouts of glee," he said. "Lady, what a lark! I'd be giving cryptic statements to the press and having a daisy of a time all over the Solar System.

"Weston is one of us. When he regains his perspective he'll view it the same way—as a lark! Right now, though," he said seriously, "it's best that he stay out of the public eye. I'd hate to have the Space Corps judged by his standards."

"I guess we all feel sorry for him," she said.

"Yeah, but it's sorrow for his mental state and not for the cause. Now forget him and enjoy yourself."

CHAPTER III

The Cold Trail

Weston strode from the party in an angry frame of mind that left him only as he entered his own ship. His anger simmered down to resentment and a bulldog determination to show them all. So they had sent a man to do a boy's work! Well, he would apply himself and ship them the answer complete down to the last decimal place!

If he had to catalogue every Jordan Green mark as to place and location in a long list and show proof of just which joking officer had scrawled it there, by heaven he'd do it. And if it made every man in the Corps a joker, that was too bad. But he would dig out the writer of each and every scrawl in the Solar System if it took the rest of his life.

He faced the piles of data and set to work with determination born of burning resentment. Morning came, and he was still sorting, filing, deciding. The card-sorter clicked regularly, dropping the tiny cards into piles that were cross-indexed and tabulated on a master card. Reports in lengthy form, mere cards of terse data, incomplete reports—all of them he went after and scanned carefully to make some sort of mad pattern if he could.

He found himself weak from lack of sleep and fought it off with hot coffee and benzedrine until he had succeeded in unraveling the now-dusty pile of data. It was full of erroneous information and false data. If Jordan Green existed he was well-covered by the scrawlings of men who wanted to perpetuate the joke. But, finished, he sat back in amazement.

Of thirty thousand such scrawlings, twenty-seven thousand were written in the same manner!

Top it—they were written with the same chalk!

Top that—they were unmistakably in the same handwriting!

"Now where in Hades did any one man get so much time?" Al Weston asked himself.

He pored over a globe of Terra, stuck pins in it to show the location, then studied it to see if any pattern could be made of the grand scramble. There was apparently none, so he took a Mercator and did the same, standing off in a dim light to see if the pin-points caused any 'lining' of the vision into some recognizable pattern.

He got a chart of Mars and studied it. He tried to make the spatter-pattern of Mars line up to agree with the pin-pattern of Terra. He turned it this way and that to see. He photographed both and laid them on top of one another, and finally gave up. There was no significance.

He went to bed and, the next morning, dropped his ship at Marsport.

"I've a four-mark commission," he said sharply to the office aide at Marsquarters.

"I'll request an audience for you," said the office aide. He should, by all rights, be slightly cowed by the senior captain's rank and the free commission, but he was aide to the High Brass of conquered Mars and larger brass than this had come and gone—unsatisfied.

"See here, I'm on a roving commission and I want aid."

"Yes sir, I'll request you an audience—"

"Blast!" snarled Weston angrily. "I'm not fooling."

"No one fools here," returned the aide.

"Are you being insolent?"

"Not if I can avoid it, sir. But you understand that I am responsible only to Admiral Callahan. I am doing his bidding and those are his wishes."

"You've not spoken to him about them."

"I need not—which is why I'm his aide. You see, sir, I'm not trying to tell you your business, but there is a lot of important work going on here."

"Will you contact him?"

"No, sir."

"I order you."

"I'd think twice, sir. I am not being personally obstinate nor am I ignorant of your rank, Senior Captain Weston. But I know Admiral Callahan's temperament."

"My order stands," said Weston, "I will be received."

"Yes sir. I'm sorry, sir." The aide turned and entered the office. He emerged, shortly afterwards and motioned for Al to enter. Weston cast a down-his-nose glance at the aide, then shut the door behind him. Against the wall beside the door was a scrawled legend.

"Jordan Green has been here, too!"

The style was unmistakable—as unmistakable as the wrath that greeted him.

"Explain, Senior Captain Weston!"

"I am on a roving commission, rank four-mark, I—"

"I'm aware of your rank, your mission and your commission. Come to the point. I want to know why you think you are more important than anybody else!"

"I—have not that opinion, sir."

"You must have it, or you'd not have behaved as you did! Come on, speak."

"Well, sir, I've uncovered a rather startling bit—"

"So what? So you demand my time to discuss a space gag with me? So they're all the same handwriting. Any idiot at Intelligence could have told you that. They covered that phase when Jordan Green first appeared. They were suspicious. Here!"

Admiral Callahan strode to a file cabinet and took out a thick file. He hurled it at Al Weston.

"Read it and learn some sense, young man. Now get out of here and don't bother coming back."

Weston took the file and left. His ears were burning and his mind was a tangle of cross-purposes and emotions. That was a rotten way to treat a man who'd been shot down on the first directive expedition.

He'd like to clip the so-and-so admiral's wings a bit. He'd—take it—he guessed, sourly, hearing a slight snicker behind him. He turned angrily but there was no one near.

That snicker? Was it real, or merely a breath of wind against the Venetian blind?

He entered the first bar he found. "Pulga and water," he said.

The bartender winced. "Does the Terran Captain forget that this is Mars?"

Weston had, but this was no time to admit a mistake.

"Not at all," he said.

"May I ask the Terran Captain to change his order?"

"I want it as I said it," snapped Weston.

"Does the Terran Captain understand that water is not plentiful? We on Mars have not the—the—plumbing as on Terra, where you cannot live without your water. We use but little personally and that mostly for washing. In washing, we absorb sufficient for our own metabolism."

"I'm aware of that."

"Then the Terran Captain may also be aware of the fact that our water is not—well—suited for internal consumption?"

"You have no bottled water?" demanded Weston angrily.

"That will be found only on the Terran Post. Please, be not angry. All newcomers forget."

"Forget it," snapped Weston and walked out.

Even the lowly bartenders of a conquered race made a fool of him. He entered another bar down the street and asked for pulga and vin, a completely native Martian potable. It was served without argument and went down right.

He had another and was halfway through it when he turned to see friends entering.

"Al!" they called. "How's it, man?"

With a weak smile he set down his drink and held out a welcoming hand.

"Hi, fellows. Haven't seen you in a year, Jack. Nor you, Bill. What's new?"

"Nothing much. Golly, we thought you were a real goner when they hit you that fatal day."

"I don't remember," said Weston.

"I'll bet you don't," said Bill with a smile. "You dropped back out of formation in a flaming instant and were gone. The rest of us were all right and won through. We hit Mars about o-three-hundred the next afternoon and, brother, did we hit 'em.

"We hurled the directive beam right down in the middle of Kanthanappois and laid the city flat! Then we headed North to Montharrin and singed 'em gently around the edges. You have no idea, Al boy, what a fierce thing you can toss out of a one-seater scooter when you've got directive power in it.

"They've never got the Fresno Beams down to a size practical for anything smaller than an eight-man job, you know. Well, directives make it possible to handle a four-turret from a one-man job. And a super-craft can carry enough stuff to move Mars."

"I missed it."

"We know, and we're sorry about that. Well, we can't all win."

"Don't be patronizing," snapped Al Weston.

"Sorry. We knew you'd have given most anything to have joined in the ruckus. Well—say, Al, I hear you've got a snap job now?"

"Well," said Al, disagreeing that it was a snap, and at the same time trying to justify its importance, "I'm trying to dig out the truth of this Jordan Green thing."

"You mean like over there?" grinned Jack, pointing to the legend on the wall.

"Uh—yeah, excuse me a moment," said Weston, going over and looking at it carefully.

"Getting to be an authority, hey, Al?" laughed Bill. "Gosh, that's a laugh of a job. Bet you have your fun."

"I think it is slightly stupid," said Weston harshly.

"Could be. It's no more stupid than a lot of jobs in this man's space navy, though. They sent a space admiral out once to measure the major diameter of all spacecraft to the maximum thousandth of an inch and didn't tell him for weeks that it had a deep purpose.

"He fumed and fretted until he discovered that it took a space admiral to hold enough rank to be permitted to measure that stuff under the security regulations. Later they made all external space gear universal so that replacement quantities could be reduced. It saved about seven billion bucks—enough to pay the admiral's salary for a couple of millennia."

Jack laughed. "It's usually some lucky bird that gets these cockeyed commissions and has a swell time loafing all over the solar system on the government's dough."

"I don't consider myself lucky."

"We do," chimed one of the men. "We're stuck here along with seven million other high-brass policemen who'd rather play marbles," said Bill. "So what does it matter what you're doing, actually, so long as you're paying your way?"

"Well, I'd prefer something a bit more in my line."

"Who wouldn't?" responded Jack. "But what the heck? Remember the lines from Gilbert & Sullivan—The Private Buffoon? 'They won't blame you so long as you're funny'!"

"Very amusing," said Weston.

"Well, shucks, anytime you want to swap jobs—"

"I wouldn't mind," said Weston wistfully.

"Look, chum, take it easy. You wouldn't like sitting on your unretractable landing gear eight hours a day listening to a bunch of dirty Marties trying to talk you into slipping them a bit of a lush. Make you damned sick.

"But it's a job we've got to do and so long as we're hung with it, we're hung, and we'll give it our best. We know we can do most anything, so why should we worry?"

Bill grinned and nodded. "I'll bet even the bartender wouldn't like our job. Hey Soupy!"

"Would the Terran officers desire something?"

"Can you be honest?"

"Can anyone?" returned the barkeep. Like all barkeeps, he was about to start walking a fence between customers.

"How would you like to have my job?"

The barkeep looked at Bill. "You want an answer?"

Bill nodded.

The barkeep shook his head. "Too much trouble. I am happy as I am. I, Terran officers, can mix the best veliqua on Mars, and no one on Terra can mix one at all. So I cannot drive a spacer, nor build a long range communicator. But I mix the best veliqua—observe?"

They observed as the barkeep made rapid motions with several bottles, whirled them overhead and came in on a tangent landing with three glasses, brimful to a bulging meniscus, without spilling a drop.

"Personally," grinned Bill, "I think we've just been hydraulic-pressured into buying a drink."

"Smart lad, he."

"I'd not put up with that. We didn't ask for it," objected Weston.

"No? Well, so what," grinned Bill, lifting the glass.

"It's okay," said Jack "But look, Al. You still sound as though you were enjoying life—or should be."

"I'm not."

"Well, Al, if you aren't, it's your fault."

"It wasn't my fault that I got clipped?"

"Hardly. No one is putting any blame on you for getting hung on the wrong end of a beam. Despite popular rumor, they don't hand out them things for cutting your hand on a can-opener," said Bill, nodding toward the purple ribbon on Weston's breast. It was beside another colored bit, awarded for his efforts in the initial directive attack.

"That one," said Weston, catching Bill's eye, "was a consolation prize. I didn't earn it."

"My friend, you must learn to tell the difference between humility and the job of fishing for compliments. Well, chum, you've had a rough time and we gotta go back and play traffic cop. Let us know if there's anything we can do."

Weston nodded. They left. They left him alone. Far back in his mind something mentioned the fact that they were on duty, but he thought they could have stayed around a bit longer.

He drank too much that long Martian afternoon and was definitely hung over most of the next day.

Al Weston gave up at that point. Never again would he try to prove his sorry plight to any one of his former friends. They all insisted upon looking at the brighter side of his life and ignored his trouble as though it did not exist.

They were glad enough to see him alive, it seemed, when he'd have preferred death to this lack-luster existence. He wondered whether any of them would worry about him if he disappeared. Perhaps if they thought he were dead—

Well, he had a four-mark commission, which entitled him among other things to commandeer anything now in the experimental field. He'd make a show of commandeering a directive power drive and then drop out of sight.

They'd suspect both his untimely end, and suspect the advisability of the directive drive. Then he'd show up and prove both worthy. That would give him his prestige again.

He'd do it at Pluto and, on the way, he'd stop at every way-station long enough to leave a wide trail. He'd enter a post, discuss Jordan Green at length. He'd take pictures, make tests and then head outward—to disappear for about a year. That would fix them all.

CHAPTER IV

Free For All

"Pluto," said Al Weston drily. He'd come through the entrance dome of one of the sealed cities and was standing atop the Corps Administration building, looking out over the sprawling city. Since Pluto was utterly cold, the sealed cities were the only habitable places on the planet and even they were too chilly for comfort.

He had no Pluto-garb, but he did have his spaceman's suit, which was internally heated. He, like most of the Corpsmen there, wore the spaceman's suit with the fishbowl swung back across his shoulderblades.

Some of them had had the helmets removed entirely, though this was troublesome around the entrance-locks because none of the men who were without their fishbowl headgear could work outside of the inner lock.

But—this was Pluto, and from here, as soon as he could leave, Al Weston was heading, just plain out!

In accordance with regulations he reported to the port commandant's office. This time he had no intention of forcing entry to the Inner Sanctum. His ears were still red from his last abortive effort. All he intended to do was to report to the office aide and, if the Big Brass wanted to see him, he'd eventually call.

Inside of the office was the usual scrawl—Yes, Jordan Green has been even here!

It was authentic and Weston said so aloud. The office aide looked up. "You're Senior Captain Weston?"

"I'm known?" asked he, slightly surprised.

"By reputation," grinned the clerk. "It's said that you can tell an authentic Jordan Green by seeing it through a visiscope."

"Not quite," said Weston.

"Have you uncovered anything yet, sir?" asked the aide.

"Are you interested?"

"Everyone is interested," said the clerk. "It will make a darned amusing yarn when you get all done."

"Uh-huh," grunted Weston. Amusing, he thought. Was his value to the Space Corps only an amusement value?

"See here," he said to the clerk, "I'd like to try a directive power drive."

"You were on the first directive power expedition against Mars, weren't you?" mused the clerk. "According to custom and regulations, you are entitled to any experimental equipment that you used during the war. Seems to me, too, that you are probably using more power for space flight than about ninety-eight percent of the corps at the present time. We have a directive power unit here."

"Then I can have it immediately?"

The clerk nodded. "I'm merely ruminating," he said to Weston. "I'd prefer several good reasons why you took it other than your fancy to try it out. It'll make the Old Man less fratchy.

"It's slightly haywire, of course, since it came right from the Power Laboratory with a boatload of long-hairs on a test mission. They left it here and we've been tinkering with it off and on. We can get a new one in a month or so, but you can have the haywire model if you'd prefer not to wait."

"I'll take it."

"Okay. I'll issue orders for the engine gang to swap power in your crate."

"Thanks," said Weston.

"Oh, and sir, I almost forgot. It's just an unfounded rumor and I've been unable to check the truth of it, but they claim there's a Jordan Green scrawl on Nergal, too."

"Nergal?" said Weston explosively. His mind envisioned a minute hunk of cosmic dust not much more than a hundred miles in diameter—Pluto's only claim to a satellite. It was better than thirteen million miles from Pluto and its rotation was necessarily slow due to its tiny mass and great distance.

It had been and would continue to be for some years, the solar object most distant from Sol.

It was uninhabited, airless, cold, forbidding, and completely useless.

There was not even a station on it. Science found the airless outer surface of Pluto more to their liking. On Pluto, at least, there was gravity to hold them down. The escape velocity of Nergal was not really known, but it must have been minute.

"Might be sheer fancy," said the clerk apologetically.

"Better check on it," said Weston. This was an opportunity. When he left it would be recorded that he went to Nergal. He even wished that he'd started to write his own name under the countless Jordan Green scrawls he'd visited. Then they could find one out there, and know he'd been there and from there...?

In relaxation uniform, Weston sat in a small, out of the way restaurant and finished his dinner. He was the only uniformed man in the place, and so when the unlovely pair behind him made mention of the Corps, he knew they were talking about him.

He did not know them by name, but after a glimpse of them immediately labeled one of them as 'Dirty' and the other one as 'Ratty'. It was Ratty's voice that caught his attention. He missed the statement, but caught Dirty's answer.

"By the time all the Fancy Brass gets them, maybe we can have a couple too."

"The war's over," Ratty snarled. "Why does the Corps need directive drives?"

"How should I know? Ask Pretty, up there."

"He wouldn't know," snapped Ratty. "He's just taking orders."

"Must be nice to roam all over space with your feed and power free."

"Yeah, but he'd go broke if he had to live on what he's worth."

"That's why most guys get in the Corps anyway."

"That guy is spending about thirty thousand bucks just to track down a myth."

"Maybe his myth has a sister for me?" guffawed Dirty. "Wonder where he was hiding when the shooting was going on."

"He wouldn't say," grunted Ratty. "Mosta the dirty work was done by draftees."

"Well, now the schemozzle is over, he'll come out beating his chest and telling how he won the war. I'll bet he piloted a office desk and got that wound ribbon from pinching his finger in a desk drawer."

"Yeah, the Corps is rotten with slinkers."

"He's tooken months to track down this myth. Bet he makes it another year. Then they'll hang a medal on him for it."

"Any good spaceman could run Jordan Green down in a week," grunted Ratty.

"But it wouldn't be profitable to do it quick," answered Dirty with a leer in his voice.

Weston got up and went to their table.

"Sit down!" he snarled. "You, too!" he snapped at Dirty, taking the man by the jacket front and ramming him back in his chair with a crash. Heads looked up, and men faded back out of the way, clearing the area.

"One," said Weston. "I was in the hospital for seven months, unconscious from a fracas off Mars with the first directive power attack. Remember? I was doing a job so that stinkers like you could roam space unbothered by Martie pirates. Where were you? Hiding in a mine somewhere?

"At the present time if I spend five years rambling all over space looking for Jordan Green, you'll still owe me plenty. I wasn't making money while I was fighting. How much did you make? If it hadn't been for the Corps you'd be dead."

Weston cuffed Dirty across the face with the back of his hand and spat into Ratty's face.

They rose with a roar and Ratty hurled table and chairs out of the way. They rushed Weston heavily.

Weston grinned.

He drove his fist into Ratty's stomach and sliced Dirty's throat with the edge of his hand.

Here was something tangible for Weston to fight! For almost a year, he had been railing at the wind, storming at an invisible hand of fate that had clipped him hard. The men before him were the embodiment of all his ill luck and he drove into them with a burning hatred to maim and destroy.

It was a dirty fight. The space rats had no qualms about sportsmanship and Weston had been tumble-trained on Terra to accept battle only when it was inevitable, at which point nothing was barred.

Dirty came in, hammering at his abdomen, and got a knee in the face. Ratty pulled a knife and rushed in with a slicing swing. Weston faded back, hit the bar, felt its edge crease his back as the rats moved after him.

He lashed out with a foot and drove Ratty and his knife back, turned to roll with a roundhouse swing from Dirty and his right arm knocked over a beer bottle. His right hand closed on the neck of the bottle, and he rapped it sharply against the edge of the bar, knocking off the base.

He kneed Dirty and closed with Ratty. He caught the knife-wielder in the face with the jagged bottle and thrust him back with a twisting punch of the bottle. There was a wordless scream.

Weston caught Dirty in the ribs with a hard fist and then cracked the man's head with what was left of the bottle. It shattered completely as Dirty staggered back and Weston dropped the useless end. They closed again, and wrestled viciously across the floor, tripped over a table and went down with a crash in a tight lock.

Dirty swung his elbow free and Weston missed catching it in the throat by a mite. Weston let go of Dirty's wrist and grabbed Dirty by the collar. Up he lifted and down he slammed.

Dirty's head made a thudding crack against the floor.

"Rye," gasped Weston and swallowed it neat.

Then he walked out, paused at the door and said:

"Call the cops and tell 'em to pick up—"

He left with a quizzical smile. He didn't even know their names.

He didn't stop to clean up, but entered his ship immediately. The directive power drive had been installed and he made radio contact with the control center that opened the locks in the sealed city.

He went out with a rush and hit the high trail for Nergal.

They'd give him a stupid job, would they? Well, he'd frittered enough on it. Now he was going to polish this off in a hurry and go back and hurl his commission in the teeth of Big Brass and stamp out snarling. A big strong man hunting a myth...!

Nergal appeared within minutes under the directive drive. He landed and slapped the magnets on to keep him down. If there were anything to this rumor Jordan Green would have needed a wall or something to write his name on.

In the scanner Weston searched every square yard of his horizon and then moved. Four times he moved, each time searching his very limited line of sight circle. The fifth time he came upon a sheet of metal, fixed to a metal post, emanating out of a box.

He looped the ship into the air, caught box and post with a tractor and pulled it into the airlock.

Drifting free, he inspected the slab of metal.

Jordan Green has been here, it said in bold letters.

And below, on the top of the box, there was a pointer in gimbals. A surveyor's telescope. Gyro-stabilized it was and it pointed off slightly below the plane of the ecliptic. Weston took it to the observation dome and applied his eye to it as it stood. In the narrow field he saw the stars, and the crosshairs centered on a small one. Around the circumference of the reticule, tiny letters shone:

Jordan Green has been there too!

The star was Proxima Centauri.

"Oh, yeah?" growled Weston angrily. "That I have to see!"

Feeling challenged and outraged, Al Weston shoved in the Directive Power Drive all the way and headed across interstellar space for Proxima Centauri.

"Jordan Green!" he growled as the ship passed above the velocity of light. "That Jordan Green!"

He forgot the incongruity of Al Weston, the first man to penetrate interstellar space—seeking a phantom that claimed to have been on Alpha Centauri or, more practically, on one of the star's planets. All that Weston knew was that Jordan Green had been having fun at the expense of the Space Corps, just as Ratty and Dirty had in riding him.

It was a private fight. He might hate the High Command's brass but let no craven civilian criticize so much as the polish on the buttons of the third-assistant lubrication technician's uniform!

Jordan Green indeed! Well, Senior Captain Alfred Weston would bring this Jordan Green in by the ears.

And then they'd let Jordan Green explain his pranks.

CHAPTER V

Trail's End

The humiliation of his project died. He began to feel a hearty dislike for Jordan Green. Not only had the joker caused waste of time and money and kilowatts during the war, he was now instrumental in the expenditure of time and money—and was keeping a qualified ranking officer from performing a task compatible with his training.

Weston growled and swore to finish up this job in quick time. He could then return to his rightful position and do a job that would set him up in his friends' eyes once more.

He considered Tony Larkin—a good enough fellow. Jeanne Tarbell—well, after all, he'd been ill and no girl could sit around all the time. Larkin was a nice enough egg and could be trusted. But Larkin would have to take a seat far to the rear when Weston returned!

He'd really show 'em!

The experimental spacecraft, driven by the experimental directive power unit, bored deeper and deeper into interstellar space and its velocity mounted high, running up an exponential scale that was calculated in terms of multiples of the speed of light.

He calculated turnover from sheer theory and a grasp of higher mathematics, since the heavens were an angry gray-blue outside of his ports. Then he decelerated and began to wait for the long long hours to pass before he could see how close his calculations were.

His clocks and chronometers went haywire and he lost track of time. He slept at odd moments, as he had done on the acceleration-half of this first interstellar trip.

The idea of interstellar travel came home to him. He, Al Weston, was making the first interstellar trip. The incongruity was not considered. He knew that he would find Jordan Green on some planet of Proxima Centauri. He began to enjoy the idea. His friends, Tom, Bill, Jack, all of them had considered him lucky. Well, confound Jordan Green, he was lucky!

And, regardless of what Jordan Green meant, he'd go down in history, not as a conquerer that went out with the Solar System's most destructive invention, but as the first peacetime user of directive power for interstellar flight. He'd comb the Centaurian system, and then return home with proof. He'd be his own hero!

His ship's velocity dropped below light and he set course for Proxima IV as a guess. He checked the panoramic receiver, located one very heavy signal coming from that planet and knew that he was right.

Not only would he be a Terran celebrity, he would also be an ambassador—first interstellar user of directive power and first discoverer of an extra-solar race of intelligences!

The planet was unpopulated!

Thick jungle covered it and it was full of wild life. On no hand could he see any sign of culture. There was no evidence but the single heavy signal, which he tracked halfway around the jungle-laden planet to land in a clearing beside a huge, white-marble building.

On the lintel above the door were the words, in letters of shimmering jewel-like substance.

Here lives Jordan Green!

Weston smiled cynically. This—was it! He polished the knuckles of his right hand in the palm of his left hand, flexed both hands, loosed the needler in his holster and strode forward, hands at his sides, alert.

He hit the door with a hard straight-arm and sent it crashing open.

He faced four people, three men and a woman.

"Well, well!" he said, one portion of his mind wondering what to do about the woman when the shooting started. He disliked harming women but he knew that women had no compunctions against doing a man as best they could.

"Which of you—or how many of you—is or are Jordan Green?"

"Why?" asked the elder man mildly.

"Because I want to strangle him—or even her—slowly and painfully! Then I'm taking him—he, she or it—back to Terra to answer some questions!"

"Why?" asked the man. "Has he harmed you?"

Weston stopped short. To be honest with himself, Jordan Green had harmed no one, but he had been a plagued nuisance at least to Weston personally. Jordan Green was a sort of a symbol of something that caused him trouble.

"See here," he said. "They hung the job of locating Jordan Green on me, thinking I needed some sort of cockeyed feather nest of a job because I couldn't handle anything real. I didn't want it, but they've tossed time and money into the job.

"Me—I want to take the joker back by the ears and show them that at least I'm worth their time and money and let them figure out whether my efforts were worth it. At least I've paid my way and done what they wanted me to do! Now—which?"

"What do you intend to do then?" asked the man. The younger man headed for a huge machine that stood inert, its pilot lights glimmering to show that it was ready to perform. The older called something in a strange tongue and the other one stopped and turned with puzzlement written in every line of his body.

"Who are you?" gritted Weston.

"I am called Dalenger. He is Valentor, she, his sister, Jasentor. The fourth is Desentin."

"I'm stupefied," gritted Weston. "A fine bunch of nom de plumes. Who are you? Or do I take you all back?"

"Tell me. Why are you angry?" asked Dalenger.

Al Weston told them. He told them of his ambition and his hopes and his own personal defeats—and though he did not know it he was extending himself to convince a total stranger that he, Weston, was a very unhappy man.

"And now, which of you is responsible for all the scribbling that's been going on?" he concluded.

Dalenger smiled. "Please sit down, Senior Captain Weston. Jasey! Get him a dollop of refreshments. I think we're about a have a talk!"

"Get to the point," snapped Weston.

"Patience, my friend. Look. Look well and see this room. We are official observers for the Galactic Union. We—"

"The what?" exploded Weston.

"In the galaxy are seventy-four suns, all peopled with humanoid races, entire stellar systems of us. We all possess what you call directive power. Not only is directive power the key to interstellar flight, but it is also the key to supremacy. That machine back there is an example. If the button behind the safety door is pressed your star will become a supernova because of our development of directive power.

"With such a means of wiping out an entire star-system, we must be certain that any newcomers who develop directive power will not be of a culture that is basically warlike, or filled with manifest destiny to rule the galaxy.

"This is harsh judgment, Senior Captain Weston, but it is a matter of being harsh or losing our lives. We are not cruel, but we are not soft where our future is at stake.

"Ergo, our detectors cover the galaxy, a job that would be impossible to do manually. At the first release of directive power we set up an observation post, such as you have found here, and we provide means to ensure a quick decision.

"When the first flight arrives we can judge the culture from the men who come with it. If the culture is favorable to the Galactic Union it is joined. If it is inimical or undesirable in any way, their sun becomes a supernova, wiping out the undesirable civilization immediately."

Weston looked at Dalenger with a hard, cynical glance.

"Like to play at being God?" he asked sharply.

"We do not. But we like to live!"

"You, I gather, are responsible for that Jordan Green gag?"

Dalenger smiled. "Yes. Your people have no doubt wondered how the fellow could get around as he did. Actually, it was a controlled-writing, using directive power from here. We have come no closer to your sun than this. Our grasp of your language was obtained by reading books, by listening to your radio and by other means—all available across the light-years by directive power.

"You see," said Dalenger, "if we came as emissaries we would be shown only that which your leaders wanted us to see. If we came as spies there would always be suspicion in your minds. Our spying is restricted to learning your language and setting up the means by which you will seek us out."

"But this Jordan Green business?"

"There are a number of reasons why a race will seek the origin of such a joke. A well-developed sense of humor and the willingness to spend money on such is desirable. Suspicion is not bad, depending upon whether it is sheer hatred of the alien or a desire to maintain integrity."

Weston thought for a moment. They were going to judge his race by him. He considered and came to the conclusion that he was a sorry specimen to grade an entire culture on.

"How can you grade a race on one specimen?" he said.

"Since the specimen is usually a competent man, highly trained, a scientist, we normally discount him a bit. A hand-picked sample is never representative, but represents the peak of the race."

Weston swallowed. "But look," he said. "That is not fair. I'm—"

"Senior Captain Weston, you strode in here angry. You displayed no sense of humor. You snarled and promised us all bodily harm and accused us of having interfered with your plans. Right?"

"Yes—but—"

"Yet," said Dalenger, "you were changing. You see, Weston, you were a sick man. There is one characteristic that is quite desirable. It is a sense of social responsibility to the individual by the collective government. Most undesirable is the type that claims the individual must be immersed in the good of the state.

"In one extension this sense is called pity. In the other extension it is called pride. You were hurt and you became ill mentally. And, instead of casting you out, your fellow men gave you a job that would result in your convalescence regardless of success or failure, providing that you yourself managed to follow through—in any manner. You did, by desperation and anger.

"We don't always judge by the mental calibre of the man who comes. We must consider the reason why he was selected. We don't value personal feelings in judgment of a race—we'd be inevitably wrong if we valued the opinion of a psychoneurotic.

"The judging was finished when I called Desentin to stop. He is young and impetuous and was about to press the button. So, Senior Captain Alfred Weston, we welcome you and your race to the Galactic Union!"

Weston blinked. He'd fought against it. He'd been angry at something every instant of the time between his awakening after the disaster to the present moment—angry because there was nothing he could do to gain real recognition. So they hung a joke-job on him to cure him!

And, by the grace of the gods and a long-handled spoon, he had walked into a situation that might have caused the destruction of the entire Solar System but for some deep understanding on the part of an alien culture.

He—Al Weston, psychoneurotic—in the position of being an emissary!

He took the glass offered by Jasentor, lifted it to the four of them and drained it with a gesture.

And for the first time in more than a year, the sound of Weston's honest laughter filled the room.

Cured!

.jpg)