Birds of a Feather

By ROBERT SILVERBERG

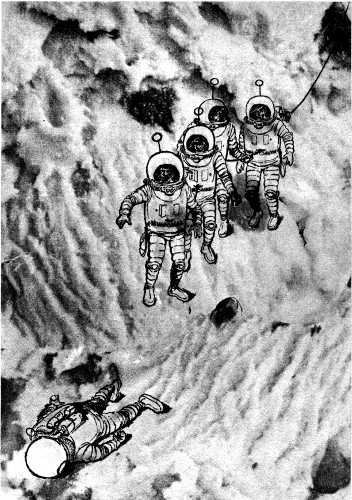

Illustrated by WOOD

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine November 1958.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Getting specimens for the interstellar zoo

was no problem—they battled for the honor—but

now I had to fight like a wildcat to

keep a display from making a monkey of me!

It was our first day of recruiting on the planet, and the alien life-forms had lined up for hundreds of feet back from my rented office. As I came down the block from the hotel, I could hear and see and smell them with ease.

My three staff men, Auchinleck, Stebbins and Ludlow, walked shieldwise in front of me. I peered between them to size the crop up. The aliens came in every shape and form, in all colors and textures—and all of them eager for a Corrigan contract. The Galaxy is full of bizarre beings, but there's barely a species anywhere that can resist the old exhibitionist urge.

"Send them in one at a time," I told Stebbins. I ducked into the office, took my place back of the desk and waited for the procession to begin.

The name of the planet was MacTavish IV (if you went by the official Terran listing) or Ghryne (if you called it by what its people were accustomed to calling it). I thought of it privately as MacTavish IV and referred to it publicly as Ghryne. I believe in keeping the locals happy wherever I go.

Through the front window of the office, I could see our big gay tridim sign plastered to a facing wall: WANTED—EXTRATERRESTRIALS! We had saturated MacTavish IV with our promotional poop for a month preceding arrival. Stuff like this:

Want to visit Earth—see the Galaxy's most glittering and exclusive world? Want to draw good pay, work short hours, experience the thrills of show business on romantic Terra? If you are a non-terrestrial, there may be a place for you in the Corrigan Institute of Morphological Science. No freaks wanted—normal beings only. J. F. Corrigan will hold interviews in person on Ghryne from Thirdday to Fifthday of Tenmonth. His last visit to the Caledonia Cluster until 2937, so don't miss your chance! Hurry! A life of wonder and riches can be yours!

Broadsides like that, distributed wholesale in half a thousand languages, always bring them running. And the Corrigan Institute really packs in the crowds back on Earth. Why not? It's the best of its kind, the only really decent place where Earthmen can get a gander at the other species of the universe.

The office buzzer sounded. Auchinleck said unctuously, "The first applicant is ready to see you, sir."

"Send him, her or it in."

The door opened and a timid-looking life-form advanced toward me on nervous little legs. He was a globular creature about the size of a big basketball, yellowish-green, with two spindly double-kneed legs and five double-elbowed arms, the latter spaced regularly around his body. There was a lidless eye at the top of his head and five lidded ones, one above each arm. Plus a big, gaping, toothless mouth.

His voice was a surprisingly resounding basso. "You are Mr. Corrigan?"

"That's right." I reached for a data blank. "Before we begin, I'll need certain information about—"

"I am a being of Regulus II," came the grave, booming reply, even before I had picked up the blank. "I need no special care and I am not a fugitive from the law of any world."

"Your name?"

"Lawrence R. Fitzgerald."

I throttled my exclamation of surprise, concealing it behind a quick cough. "Let me have that again, please?"

"Certainly. My name is Lawrence R. Fitzgerald. The 'R' stands for Raymond."

"Of course, that's not the name you were born with."

The being closed his eyes and toddled around in a 360-degree rotation, remaining in place. On his world, that gesture is the equivalent of an apologetic smile. "My Regulan name no longer matters. I am now and shall evermore be Lawrence R. Fitzgerald. I am a Terraphile, you see."

The little Regulan was as good as hired. Only the formalities remained. "You understand our terms, Mr. Fitzgerald?"

"I'll be placed on exhibition at your Institute on Earth. You'll pay for my services, transportation and expenses. I'll be required to remain on exhibit no more than one-third of each Terran sidereal day."

"And the pay will be—ah—$50 Galactic a week, plus expenses and transportation."

The spherical creature clapped his hands in joy, three hands clapping on one side, two on the other. "Wonderful! I will see Earth at last! I accept the terms!"

I buzzed for Ludlow and gave him the fast signal that meant we were signing this alien up at half the usual pay, and Ludlow took him into the other office to sign him up.

I grinned, pleased with myself. We needed a green Regulan in our show; the last one had quit four years ago. But just because we needed him didn't mean we had to be extravagant in hiring him. A Terraphile alien who goes to the extent of rechristening himself with a Terran monicker would work for nothing, or even pay us, just so long as we let him get to Earth. My conscience won't let me really exploit a being, but I don't believe in throwing money away, either.

The next applicant was a beefy ursinoid from Aldebaran IX. Our outfit has all the ursinoids it needs or is likely to need in the next few decades, and so I got rid of him in a couple of minutes. He was followed by a roly-poly blue-skinned humanoid from Donovan's Planet, four feet high and five hundred pounds heavy. We already had a couple of his species in the show, but they made good crowd-pleasers, being so plump and cheerful. I passed him along to Auchinleck to sign at anything short of top rate.

Next came a bedraggled Sirian spider who was more interested in a handout than a job. If there's any species we have a real over-supply of, it's those silver-colored spiders, but this seedy specimen gave it a try anyway. He got the gate in half a minute, and he didn't even get the handout he was angling for. I don't approve of begging.

The flora of applicants was steady. Ghryne is in the heart of the Caledonia Cluster, where the interstellar crossroads meet. We had figured to pick up plenty of new exhibits here and we were right.

It was the isolationism of the late 29th century that turned me into the successful proprietor of Corrigan's Institute, after some years as an impoverished carnival man in the Betelgeuse system. Back in 2903, the World Congress declared Terra off-bounds for non-terrestrial beings, as an offshoot of the Terra for Terrans movement.

Before then, anyone could visit Earth. After the gate clanged down, a non-terrestrial could only get onto Sol III as a specimen in a scientific collection—in short, as an exhibit in a zoo.

That's what the Corrigan Institute of Morphological Science really is, of course. A zoo. But we don't go out and hunt for our specimens; we advertise and they come flocking to us. Every alien wants to see Earth once in his lifetime, and there's only one way he can do it.

We don't keep too big an inventory. At last count, we had 690 specimens before this trip, representing 298 different intelligent life-forms. My goal is at least one member of at least 500 different races. When I reach that, I'll sit back and let the competition catch up—if it can.

After an hour of steady work that morning, we had signed eleven new specimens. At the same time, we had turned away a dozen ursinoids, fifty of the reptilian natives of Ghryne, seven Sirian spiders, and no less than nineteen chlorine-breathing Procyonites wearing gas masks.

It was also my sad duty to nix a Vegan who was negotiating through a Ghrynian agent. A Vegan would be a top-flight attraction, being some 400 feet long and appropriately fearsome to the eye, but I didn't see how we could take one on. They're gentle and likable beings, but their upkeep runs into literally tons of fresh meat a day, and not just any old kind of meat either. So we had to do without the Vegan.

"One more specimen before lunch," I told Stebbins, "to make it an even dozen."

He looked at me queerly and nodded. A being entered. I took a long close look at the life-form when it came in, and after that I took another one. I wondered what kind of stunt was being pulled. So far as I could tell, the being was quite plainly nothing but an Earthman.

He sat down facing me without being asked and crossed his legs. He was tall and extremely thin, with pale blue eyes and dirty-blond hair, and though he was clean and reasonably well dressed, he had a shabby look about him. He said, in level Terran accents, "I'm looking for a job with your outfit, Corrigan."

"There's been a mistake. We're interested in non-terrestrials only."

"I'm a non-terrestrial. My name is Ildwar Gorb, of the planet Wazzenazz XIII."

I don't mind conning the public from time to time, but I draw the line at getting bilked myself. "Look, friend, I'm busy, and I'm not known for my sense of humor. Or my generosity."

"I'm not panhandling. I'm looking for a job."

"Then try elsewhere. Suppose you stop wasting my time, bud. You're as Earthborn as I am."

"I've never been within a dozen parsecs of Earth," he said smoothly. "I happen to be a representative of the only Earthlike race that exists anywhere in the Galaxy but on Earth itself. Wazzenazz XIII is a small and little-known planet in the Crab Nebula. Through an evolutionary fluke, my race is identical with yours. Now, don't you want me in your circus?"

"No. And it's not a circus. It's—"

"A scientific institute. I stand corrected."

There was something glib and appealing about this preposterous phony. I guess I recognized a kindred spirit or I would have tossed him out on his ear without another word. Instead I played along. "If you're from such a distant place, how come you speak English so well?"

"I'm not speaking. I'm a telepath—not the kind that reads minds, just the kind that projects. I communicate in symbols that you translate back to colloquial speech."

"Very clever, Mr. Gorb." I grinned at him and shook my head. "You spin a good yarn—but for my money, you're really Sam Jones or Phil Smith from Earth, stranded here and out of cash. You want a free trip back to Earth. No deal. The demand for beings from Wazzenazz XIII is pretty low these days. Zero, in fact. Good-by, Mr. Gorb."

He pointed a finger squarely at me and said, "You're making a big mistake. I'm just what your outfit needs. A representative of a hitherto utterly unknown race identical to humanity in every respect! Look here, examine my teeth. Absolutely like human teeth! And—"

I pulled away from his yawning mouth. "Good-by, Mr. Gorb," I repeated.

"All I ask is a contract, Corrigan. It isn't much. I'll be a big attraction. I'll—"

"Good-by, Mr. Gorb!"

He glowered at me reproachfully for a moment, stood up and sauntered to the door. "I thought you were a man of acumen, Corrigan. Well, think it over. Maybe you'll regret your hastiness. I'll be back to give you another chance."

He slammed the door and I let my grim expression relax into a smile. This was the best con switch yet—an Earthman posing as an alien to get a job!

But I wasn't buying it, even if I could appreciate his cleverness intellectually. There's no such place as Wazzenazz XIII and there's only one human race in the Galaxy—on Earth. I was going to need some real good reason before I gave a down-and-out grifter a free ticket home.

I didn't know it then, but before the day was out, I would have that reason. And, with it, plenty of trouble on my hands.

The first harbinger of woe turned up after lunch in the person of a Kallerian. The Kallerian was the sixth applicant that afternoon. I had turned away three more ursinoids, hired a vegetable from Miazan, and said no to a scaly pseudo-armadillo from one of the Delta Worlds. Hardly had the 'dillo scuttled dejectedly out of my office when the Kallerian came striding in, not even waiting for Stebbins to admit him officially.

He was big even for his kind—in the neighborhood of nine feet high, and getting on toward a ton. He planted himself firmly on his three stocky feet, extended his massive arms in a Kallerian greeting-gesture, and growled, "I am Vallo Heraal, Freeman of Kaller IV. You will sign me immediately to a contract."

"Sit down, Freeman Heraal. I like to make my own decisions, thanks."

"You will grant me a contract!"

"Will you please sit down?"

He said sulkily, "I will remain standing."

"As you prefer." My desk has a few concealed features which are sometimes useful in dealing with belligerent or disappointed life-forms. My fingers roamed to the meshgun trigger, just in case of trouble.

The Kallerian stood motionless before me. They're hairy creatures, and this one had a coarse, thick mat of blue fur completely covering his body. Two fierce eyes glimmered out through the otherwise dense blanket of fur. He was wearing the kilt, girdle and ceremonial blaster of his warlike race.

I said, "You'll have to understand, Freeman Heraal, that it's not our policy to maintain more than a few members of each species at our Institute. And we're not currently in need of any Kallerian males, because—"

"You will hire me or trouble I will make!"

I opened our inventory chart. I showed him that we were already carrying four Kallerians, and that was more than plenty.

The beady little eyes flashed like beacons in the fur. "Yes, you have four representatives—of the Clan Verdrokh! None of the Clan Gursdrinn! For three years, I have waited for a chance to avenge this insult to the noble Clan Gursdrinn!"

At the key-word avenge, I readied myself to ensnarl the Kallerian in a spume of tanglemesh the instant he went for his blaster, but he didn't move. He bellowed, "I have vowed a vow, Earthman. Take me to Earth, enroll a Gursdrinn, or the consequences will be terrible!"

I'm a man of principles, like all straightforward double-dealers, and one of the most important of those principles is that I never let myself be bullied by anyone. "I deeply regret having unintentionally insulted your clan, Freeman Heraal. Will you accept my apologies?"

He glared at me in silence.

I went on, "Please be assured that I'll undo the insult at the earliest possible opportunity. It's not feasible for us to hire another Kallerian now, but I'll give preference to the Clan Gursdrinn as soon as a vacancy—"

"No. You will hire me now."

"It can't be done, Freeman Heraal. We have a budget, and we stick to it."

"You will rue! I will take drastic measures!"

"Threats will get you nowhere, Freeman Heraal. I give you my word I'll get in touch with you as soon as our organization has room for another Kallerian. And now, please, there are many applicants waiting—"

You'd think it would be sort of humiliating to become a specimen in a zoo, but most of these races take it as an honor. And there's always the chance that, by picking a given member of a race, we're insulting all the others.

I nudged the trouble-button on the side of my desk and Auchinleck and Ludlow appeared simultaneously from the two doors at right and left. They surrounded the towering Kallerian and sweet-talkingly led him away. He wasn't minded to quarrel physically, or he could have knocked them both into the next city with a backhand swipe of his shaggy paw, but he kept up a growling flow of invective and threats until he was out in the hall.

I mopped sweat from my forehead and began to buzz Stebbins for the next applicant. But before my finger touched the button, the door popped open and a small being came scooting in, followed by an angry Stebbins.

"Come here, you!"

"Stebbins?" I said gently.

"I'm sorry, Mr. Corrigan. I lost sight of this one for a moment, and he came running in—"

"Please, please," squeaked the little alien pitifully. "I must see you, honored sir!"

"It isn't his turn in line," Stebbins protested. "There are at least fifty ahead of him."

"All right," I said tiredly. "As long as he's in here already, I might as well see him. Be more careful next time, Stebbins."

Stebbins nodded dolefully and backed out.

The alien was a pathetic sight: a Stortulian, a squirrely-looking creature about three feet high. His fur, which should have been a lustrous black, was a dull gray, and his eyes were wet and sad. His tail drooped. His voice was little more than a faint whimper, even at full volume.

"Begging your most honored pardon most humbly, important sir. I am a being of Stortul XII, having sold my last few possessions to travel to Ghryne for the miserable purpose of obtaining an interview with yourself."

I said, "I'd better tell you right at the outset that we're already carrying our full complement of Stortulians. We have both a male and a female now and—"

"This is known to me. The female—is her name perchance Tiress?"

I glanced down at the inventory chart until I found the Stortulian entry. "Yes, that's her name."

The little being immediately emitted a soul-shaking gasp. "It is she! It is she!"

"I'm afraid we don't have room for any more—"

"You are not in full understanding of my plight. The female Tiress, she is—was—my own Fire-sent spouse, my comfort and my warmth, my life and my love."

"Funny," I said. "When we signed her three years ago, she said she was single. It's right here on the chart."

"She lied! She left my burrow because she longed to see the splendors of Earth. And I am alone, bound by our sacred customs never to remarry, languishing in sadness and pining for her return. You must take me to Earth!"

"But—"

"I must see her—her and this disgrace-bringing lover of hers. I must reason with her. Earthman, can't you see I must appeal to her inner flame? I must bring her back!"

My face was expressionless. "You don't really intend to join our organization at all—you just want free passage to Earth?"

"Yes, yes!" wailed the Stortulian. "Find some other member of my race, if you must! Let me have my wife again, Earthman! Is your heart a dead lump of stone?"

It isn't, but another of my principles is to refuse to be swayed by sentiment. I felt sorry for this being's domestic troubles, but I wasn't going to break up a good act just to make an alien squirrel happy—not to mention footing the transportation.

I said, "I don't see how we can manage it. The laws are very strict on the subject of bringing alien life to Earth. It has to be for scientific purposes only. And if I know in advance that your purpose in coming isn't scientific, I can't in all conscience lie for you, can I?"

"Well—"

"Of course not." I took advantage of his pathetic upset to steam right along. "Now if you had come in here and simply asked me to sign you up, I might conceivably have done it. But no—you had to go unburden your heart to me."

"I thought the truth would move you."

"It did. But in effect you're now asking me to conspire in a fraudulent criminal act. Friend, I can't do it. My reputation means too much to me," I said piously.

"Then you will refuse me?"

"My heart melts to nothingness for you. But I can't take you to Earth."

"Perhaps you will send my wife to me here?"

There's a clause in every contract that allows me to jettison an unwanted specimen. All I have to do is declare it no longer of scientific interest, and the World Government will deport the undesirable alien back to its home world. But I wouldn't pull a low trick like that on our female Stortulian.

I said, "I'll ask her about coming home. But I won't ship her back against her will. And maybe she's happier where she is."

The Stortulian seemed to shrivel. His eyelids closed half-way to mask his tears. He turned and shambled slowly to the door, walking like a living dishrag. In a bleak voice, he said, "There is no hope then. All is lost. I will never see my soulmate again. Good day, Earthman."

He spoke in a drab monotone that almost, but not quite, had me weeping. I watched him shuffle out. I do have some conscience, and I had the uneasy feeling I had just been talking to a being who was about to commit suicide on my account.

About fifty more applicants were processed without a hitch. Then life started to get complicated again.

Nine of the fifty were okay. The rest were unacceptable for one reason or another, and they took the bad news quietly enough. The haul for the day so far was close to two dozen new life-forms under contract.

I had just about begun to forget about the incidents of the Kallerian's outraged pride and the Stortulian's flighty wife when the door opened and the Earthman who called himself Ildwar Gorb of Wazzenazz XIII stepped in.

"How did you get in here?" I demanded.

"Your man happened to be looking the wrong way," he said cheerily. "Change your mind about me yet?"

"Get out before I have you thrown out."

Gorb shrugged. "I figured you hadn't changed your mind, so I've changed my pitch a bit. If you won't believe I'm from Wazzenazz XIII, suppose I tell you that I am Earthborn, and that I'm looking for a job on your staff."

"I don't care what your story is! Get out or—"

"—you'll have me thrown out. Okay, okay. Just give me half a second. Corrigan, you're no fool, and neither am I—but that fellow of yours outside is. He doesn't know how to handle alien beings. How many times today has a life-form come in here unexpectedly?"

I scowled at him. "Too damn many."

"You see? He's incompetent. Suppose you fire him, take me on instead. I've been living in the outworlds half my life; I know all there is to know about alien life-forms. You can use me, Corrigan."

I took a deep breath and glanced all around the paneled ceiling of the office before I spoke. "Listen, Gorb, or whatever your name is, I've had a hard day. There's been a Kallerian in here who just about threatened murder, and there's been a Stortulian in here who's about to commit suicide because of me. I have a conscience and it's troubling me. But get this: I just want to finish off my recruiting, pack up and go home to Earth. I don't want you hanging around here bothering me. I'm not looking to hire new staff members, and if you switch back to claiming you're an unknown life-form from Wazzenazz XIII, the answer is that I'm not looking for any of those either. Now will you scram or—"

The office door crashed open at that point and Heraal, the Kallerian, came thundering in. He was dressed from head to toe in glittering metalfoil, and instead of his ceremonial blaster, he was wielding a sword the length of a human being. Stebbins and Auchinleck came dragging helplessly along in his wake, hanging desperately to his belt.

"Sorry, Chief," Stebbins gasped. "I tried to keep him out, but—"

Heraal, who had planted himself in front of my desk, drowned him out with a roar. "Earthman, you have mortally insulted the Clan Gursdrinn!"

Sitting with my hands poised near the meshgun trigger, I was ready to let him have it at the first sight of actual violence.

Heraal boomed, "You are responsible for what is to happen now. I have notified the authorities and you prosecuted will be for causing the death of a life-form! Suffer, Earthborn ape! Suffer!"

"Watch it, Chief," Stebbins yelled. "He's going to—"

An instant before my numb fingers could tighten on the meshgun trigger, Heraal swung that huge sword through the air and plunged it savagely through his body. He toppled forward onto the carpet with the sword projecting a couple of feet out of his back. A few driblets of bluish-purple blood spread from beneath him.

Before I could react to the big life-form's hara-kiri, the office door flew open again and three sleek reptilian beings entered, garbed in the green sashes of the local police force. Their golden eyes goggled down at the figure on the floor, then came to rest on me.

"You are J. F. Corrigan?" the leader asked.

"Y-yes."

"We have received word of a complaint against you. Said complaint being—"

"—that your unethical actions have directly contributed to the untimely death of an intelligent life-form," filled in the second of the Ghrynian policemen.

"The evidence lies before us," intoned the leader, "in the cadaver of the unfortunate Kallerian who filed the complaint with us several minutes ago."

"And therefore," said the third lizard, "it is our duty to arrest you for this crime and declare you subject to a fine of no less than $100,000 Galactic or two years in prison."

"Hold on!" I stormed. "You mean that any being from anywhere in the Universe can come in here and gut himself on my carpet, and I'm responsible?"

"This is the law. Do you deny that your stubborn refusal to yield to this late life-form's request lies at the root of his sad demise?"

"Well, no, but—"

"Failure to deny is admission of guilt. You are guilty, Earthman."

Closing my eyes wearily, I tried to wish the whole babbling lot of them away. If I had to, I could pony up the hundred-grand fine, but it was going to put an awful dent in this year's take. And I shuddered when I remembered that any minute that scrawny little Stortulian was likely to come bursting in here to kill himself too. Was it a fine of $100,000 per suicide? At that rate, I could be out of business by nightfall.

I was spared further such morbid thoughts by yet another unannounced arrival.

The small figure of the Stortulian trudged through the open doorway and stationed itself limply near the threshold. The three Ghrynian policemen and my three assistants forgot the dead Kallerian for a moment and turned to eye the newcomer.

I had visions of unending troubles with the law here on Ghryne. I resolved never to come here on a recruiting trip again—or, if I did come, to figure out some more effective way of screening myself against crackpots.

In heart-rending tones, the Stortulian declared, "Life is no longer worth living. My last hope is gone. There is only one thing left for me to do."

I was quivering at the thought of another hundred thousand smackers going down the drain. "Stop him, somebody! He's going to kill himself! He's—"

Then somebody sprinted toward me, hit me amidships, and knocked me flying out from behind my desk before I had a chance to fire the meshgun. My head walloped the floor, and for five or six seconds, I guess I wasn't fully aware of what was going on.

Gradually the scene took shape around me. There was a monstrous hole in the wall behind my desk; a smoking blaster lay on the floor, and I saw the three Ghrynian policemen sitting on the raving Stortulian. The man who called himself Ildwar Gorb was getting to his feet and dusting himself off.

He helped me up. "Sorry to have had to tackle you, Corrigan. But that Stortulian wasn't here to commit suicide, you see. He was out to get you."

I weaved dizzily toward my desk and dropped into my chair. A flying fragment of wall had deflated my pneumatic cushion. The smell of ashed plaster was everywhere. The police were effectively cocooning the struggling little alien in an unbreakable tanglemesh.

"Evidently you don't know as much as you think you do about Stortulian psychology, Corrigan," Gorb said lightly. "Suicide is completely abhorrent to them. When they're troubled, they kill the person who caused their trouble. In this case, you."

I began to chuckle—more of a tension-relieving snicker than a full-bodied laugh.

"Funny," I said.

"What is?" asked the self-styled Wazzenazzian.

"These aliens. Big blustery Heraal came in with murder in his eye and killed himself, and the pint-sized Stortulian who looked so meek and pathetic damn near blew my head off." I shuddered. "Thanks for the tackle job."

"Don't mention it," Gorb said.

I glared at the Ghrynian police. "Well? What are you waiting for? Take that murderous little beast out of here! Or isn't murder against the local laws?"

"The Stortulian will be duly punished," replied the leader of the Ghrynian cops calmly. "But there is the matter of the dead Kallerian and the fine of—"

"—one hundred thousand dollars. I know." I groaned and turned to Stebbins. "Get the Terran Consulate on the phone, Stebbins. Have them send down a legal adviser. Find out if there's any way we can get out of this mess with our skins intact."

"Right, Chief." Stebbins moved toward the visiphone.

Gorb stepped forward and put a hand on his chest.

"Hold it," the Wazzenazzian said crisply. "The Consulate can't help you. I can."

"You?" I said.

"I can get you out of this cheap."

"How cheap?"

Gorb grinned rakishly. "Five thousand in cash plus a contract as a specimen with your outfit. In advance, of course. That's a heck of a lot better than forking over a hundred grand, isn't it?"

I eyed Gorb uncertainly. The Terran Consulate people probably wouldn't be much help; they tried to keep out of local squabbles unless they were really serious, and I knew from past experiences that no officials ever worried much about the state of my pocketbook. On the other hand, giving this slyster a contract might be a risky proposition.

"Tell you what," I said finally. "You've got yourself a deal—but on a contingency basis. Get me out of this and you'll have five grand and the contract. Otherwise, nothing."

Gorb shrugged. "What have I to lose?"

Before the police could interfere, Gorb trotted over to the hulking corpse of the Kallerian and fetched it a mighty kick.

"Wake up, you faker! Stop playing possum and stand up! You aren't fooling anyone!"

The Ghrynians got off the huddled little assassin and tried to stop Gorb. "Your pardon, but the dead require your respect," began one of the lizards mildly.

Gorb whirled angrily. "Maybe the dead do—but this character isn't dead!"

He knelt and said loudly in the Kallerian's dishlike ear, "You might as well quit it, Heraal. Listen to this, you shamming mountain of meat—your mother knits doilies for the Clan Verdrokh!"

The supposedly dead Kallerian emitted a twenty-cycle rumble that shook the floor, and clambered to his feet, pulling the sword out of his body and waving it in the air. Gorb leaped back nimbly, snatched up the Stortulian's fallen blaster, and trained it neatly on the big alien's throat before he could do any damage. The Kallerian grumbled and lowered his sword.

I felt groggy. I thought I knew plenty about non-terrestrial life-forms, but I was learning a few things today. "I don't understand. How—"

The police were blue with chagrin. "A thousand pardons, Earthman. There seems to have been some error."

"There seems to have been a cute little con game," Gorb remarked quietly.

I recovered my balance. "Try to milk me of a hundred grand when there's been no crime?" I snapped. "I'll say there's been an error! If I weren't a forgiving man, I'd clap the bunch of you in jail for attempting to defraud an Earthman! Get out of here! And take that would-be murderer with you!"

They got, and they got fast, burbling apologies as they went. They had tried to fox an Earthman, and that's a dangerous sport. They dragged the cocooned form of the Stortulian with them. The air seemed to clear, and peace was restored. I signaled to Auchinleck and he slammed the door.

"All right." I looked at Gorb and jerked a thumb at the Kallerian. "That's a nice trick. How does it work?"

Gorb smiled pleasantly. He was enjoying this, I could see. "Kallerians of the Clan Gursdrinn specialize in a kind of mental discipline, Corrigan. It isn't too widely known in this area of the Galaxy, but men of that clan have unusual mental control over their bodies. They can cut off circulation and nervous-system response in large chunks of their bodies for hours at a stretch—an absolutely perfect imitation of death. And, of course, when Heraal put the sword through himself, it was a simple matter to avoid hitting any vital organs en route."

The Kallerian, still at gunpoint, hung his head in shame. I turned on him. "So—try to swindle me, eh? You cooked this whole fake suicide up in collusion with those cops."

He looked quite a sight, with that gaping slash running clear through his body. But the wound had begun to heal already. "I regret the incident, Earthman. I am mortified. Be good enough to destroy this unworthy person."

It was a tempting idea, but a notion was forming in my showman's mind. "No, I won't destroy you. Tell me—how often can you do that trick?"

"The tissues will regenerate in a few hours."

"Would you mind having to kill yourself every day, Heraal? And twice on Sundays?"

Heraal looked doubtful. "Well, for the honor of my Clan, perhaps—"

Stebbins said, "Boss, you mean—"

"Shut up. Heraal, you're hired—$75 a week plus expenses. Stebbins, get me a contract form—and type in a clause requiring Heraal to perform his suicide stunt at least five but no more than eight times a week."

I felt a satisfied glow. There's nothing more pleasing than to turn a swindle into a sure-fire crowd-puller.

"Aren't you forgetting something, Corrigan?" asked Ildwar Gorb in a quietly menacing voice. "We had a little agreement, you know."

"Oh. Yes." I moistened my lips and glanced shiftily around the office. There had been too many witnesses. I couldn't back down. I had no choice but to write out a check for five grand and give Gorb a standard alien-specimen contract. Unless....

"Just a second," I said. "To enter Earth as an alien exhibit, you need proof of alien origin."

He grinned, pulled out a batch of documents. "Nothing to it. Everything's stamped and in order—and anybody who wants to prove these papers are fraudulent will have to find Wazzenazz XIII first!"

We signed and I filed the contracts away. But only then did it occur to me that the events of the past hour might have been even more complicated than they looked. Suppose, I wondered, Gorb had conspired with Heraal to stage the fake suicide, and rung in the cops as well—with contracts for both of them the price of my getting off the hook?

It could very well be. And if it was, it meant I had been taken as neatly as any chump I'd ever conned.

Carefully keeping a poker face, I did a silent burn. Gorb, or whatever his real name was, was going to find himself living up to that contract he'd signed—every damn word and letter of it!

We left Ghryne later that week, having interviewed some eleven hundred alien life-forms and having hired fifty-two. It brought the register of our zoo—pardon me, the Institute—to a nice pleasant 742 specimens representing 326 intelligent life-forms.

Ildwar Gorb, the Wazzenazzian—who admitted that his real name was Mike Higgins, of St. Louis—turned out to be a tower of strength on the return voyage. It developed that he really did know all there was to know about alien life-forms.

When he found out I had turned down the 400-foot-long Vegan because the upkeep would be too big, Gorb-Higgins rushed off to the Vegan's agent and concluded a deal whereby we acquired a fertilized Vegan ovum, weighing hardly more than an ounce. Transporting that was a lot cheaper than lugging a full-grown adult Vegan, besides which, he assured me that the infant beast could be adapted to a diet of vegetables without any difficulty.

He made life a lot easier for me during the six-week voyage to Earth in our specially constructed ship. With fifty-two alien life-forms aboard, all sorts of dietary problems arose, not to mention the headaches that popped up over pride of place and the like. The Kallerian simply refused to be quartered anywhere but on the left-hand side of the ship, for example—but that was the side we had reserved for low-gravity creatures, and there was no room for him there.

"We'll be traveling in hyperspace all the way to Earth," Gorb-Higgins assured the stubborn Kallerian. "Our cosmostatic polarity will be reversed, you see."

"Hah?" asked Heraal in confusion.

"The cosmostatic polarity. If you take a bunk on the left-hand side of the ship, you'll be traveling on the right-hand side all the way there!"

"Oh," said the big Kallerian. "I didn't know that. Thank you for explaining."

He gratefully took the stateroom we assigned him.

Higgins really had a way with the creatures, all right. He made us look like fumbling amateurs, and I had been operating in this business more than fifteen years.

Somehow Higgins managed to be on the spot whenever trouble broke out. A highly strung Norvennith started a feud with a pair of Vanoinans over an alleged moral impropriety; Norvennithi can be very stuffy sometimes. But Gorb convinced the outraged being that what the Vanoinans were doing in the washroom was perfectly proper. Well, it was, but I'd never have thought of using that particular analogy.

I could list half a dozen other incidents in which Gorb-Higgins' special knowledge of outworld beings saved us from annoying hassles on that trip back. It was the first time I had ever had another man with brains in the organization and I was getting worried.

When I first set up the Institute back in the early 2920s, it was with my own capital, scraped together while running a comparative biology show on Betelgeuse IX. I saw to it that I was the sole owner. And I took care to hire competent but unspectacular men as my staffers—men like Stebbins, Auchinleck and Ludlow.

Only now I had a viper in my bosom, in the person of this Ildwar Gorb-Mike Higgins. He could think for himself. He knew a good racket when he saw one. We were birds of a feather, Higgins and I. I doubted if there was room for both of us in this outfit.

I sent for him just before we were about to make Earthfall, offered him a few slugs of brandy before I got to the point. "Mike, I've watched the way you handled the exhibits on the way back here."

"The other exhibits," he pointed out. "I'm one of them, not a staff man."

"Your Wazzenazzian status is just a fiction cooked up to get you past the immigration authorities, Mike. But I've got a proposition for you."

"Propose away."

"I'm getting a little too old for this starcombing routine," I said. "Up to now, I've been doing my own recruiting, but only because I couldn't trust anyone else to do the job. I think you could handle it, though." I stubbed out my cigarette and lit another. "Tell you what, Mike—I'll rip up your contract as an exhibit, and I'll give you another one as a staffman, paying twice as much. Your job will be to roam the planets finding new material for us. How about it?"

I had the new contract all drawn up. I pushed it toward him, but he put his hand down over mine and smiled amiably as he said, "No go."

"No? Not even for twice the pay?"

"I've done my own share of roaming," he said. "Don't offer me more money. I just want to settle down on Earth, Jim. I don't care about the cash. Honest."

It was very touching, and also very phony, but there was nothing I could do. I couldn't get rid of him that way. I had to bring him to Earth.

The immigration officials argued about his papers, but he'd had the things so cleverly faked that there was no way of proving he wasn't from Wazzenazz XIII. We set him up in a key spot of the building.

The Kallerian, Heraal, is one of our top attractions now. Every day at two in the afternoon, he commits ritual suicide, and soon afterward rises from death to the accompaniment of a trumpet fanfare. The four other Kallerians we had before are wildly jealous of the crowds he draws, but they're just not trained to do his act.

But the unquestioned number one attraction here is confidence man Mike Higgins. He's billed as the only absolutely human life-form from an extraterrestrial planet, and though we've had our share of debunking, it has only increased business.

Funny that the biggest draw at a zoo like ours should be a home-grown Earthman, but that's show business.

A couple of weeks after we got back, Mike added a new wrinkle to the act. He turned up with a blonde showgirl named Marie, and now we have a Woman from Wazzenazz too. It's more fun for Mike that way. And downright clever.

He's too clever, in fact. Like I said, I appreciate a good confidence man, the way some people appreciate fine wine. But I wish I had left Ildwar Gorb back on Ghryne, instead of signing him up with us.

Yesterday he stopped by at my office after we had closed down for the day. He was wearing that pleasant smile he always wears when he's up to something.

He accepted a drink, as usual, and then he said, "Jim, I was talking to Lawrence R. Fitzgerald yesterday."

"The little Regulan? The green basketball?"

"That's the one. He tells me he's only getting $50 a week. And a lot of the other boys here are drawing pretty low pay too."

My stomach gave a warning twinge. "Mike, if you're looking for a raise, I've told you time and again you're worth it to me. How about twenty a week?"

He held up one hand. "I'm not angling for a raise for me, Jim."

"What then?"

He smiled beatifically. "The boys and I held a little meeting yesterday evening, and we—ah—formed a union, with me as leader. I'd like to discuss the idea of a general wage increase for every one of the exhibits here."

"Higgins, you blackmailer, how can I afford—"

"Easy," he said. "You'd hate to lose a few weeks' gross, wouldn't you?"

"You mean you'd call a strike?"

He shrugged. "If you leave me no choice, how else can I protect my members' interests?"

After about half an hour of haggling, he sweated me into an across-the-board increase for the entire mob, with a distinct hint of further raises to come. But he also casually let me know the price he's asking to call off the hounds. He wants a partnership in the Institute; a share in the receipts.

If he gets that, it makes him a member of management, and he'll have to quit as union leader. That way I won't have him to contend with as a negotiator.

But I will have him firmly embedded in the organization, and once he gets his foot in the door, he won't be satisfied until he's on top—which means when I'm out.

But I'm not licked yet! Not after a full lifetime of conniving and swindling! I've been over and over the angles and there's one thing you can always count on—a trickster will always outsmart himself if you give him the chance. I did it with Higgins. Now he's done it with me.

He'll be back here in half an hour to find out whether he gets his partnership or not. Well, he'll get his answer. I'm going to affirm, as per the escape clause in the standard exhibit contract he signed, that he is no longer of scientific value, and the Feds will pick him up and deport him to his home world.

That leaves him two equally nasty choices.

Those fake documents of his were good enough to get him admitted to Earth as a legitimate alien. How the World Police get him back there is their headache—and his.

If he admits the papers were phony, the only way he'll get out of prison will be when it collapses of old age.

So I'll give him a third choice: He can sign an undated confession, which I will keep in my safe, as guarantee against future finagling.

I don't expect to be around forever, you see, though, with that little secret I picked up on Rimbaud II, it'll be a good long time, not even barring accidents, and I've been wondering whom to leave the Corrigan Institute of Morphological Science to. Higgins will make a fine successor.

Oh, one more thing he will have to sign. It remains the Corrigan Institute as long as the place is in business.

Try to outcon me, will he?