Destiny Times Three

By FRITZ LEIBER, Jr.

Illustrated by Orban

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Astounding Science Fiction March, April 1945.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

I.

The ash Yggdrasil great evil suffers,

Far more than men do know;

The hart bites its top, its trunk is rotting,

And Nidhogg gnaws beneath.

In ghostly, shivering streamers of green and blue, like northern

lights, the closing hues of the fourth Hoderson symchromy, called "the

Yggdrasil," shuddered down toward visual silence. Once more the ancient

myth, antedating even the Dawn Civilization, had been told—of the tree

of life with its roots in heaven and hell and the land of the frost

giants, and serpents gnawing at those roots and the gods fighting to

preserve it. Transmuted into significant color by Hoderson's genius,

interpreted by the world's greatest color instrumentalists, the

primeval legend of cosmic dread and rottenness and mystery, of wheels

within cosmic wheels, had once more enthralled its beholders.

In the grip of an unearthly excitement, Thorn crouched forward, one

hand jammed against the grassy earth beyond his outspread cloak. The

lean wrist shook. It burst upon him, as never before, how the Yggdrasil

legend paralleled the hypothesis which Clawly and he were going to

present later this night to the World Executive Committee.

More roots of reality than one, all right, and worse than serpents

gnawing, if that hypothesis were true.

And no gods to oppose them—only two fumbling, overmatched men.

Thorn stole a glance at the audience scattered across the hillside. The

upturned faces of utopia's sane, healthy citizenry seemed bloodless and

cruel and infinitely alien. Like masks. Thorn shuddered.

A dark, stooped figure slipped between him and Clawly. In the last

dying upflare of the symchromy—the last wan lightning stroke as

the storm called life departed from the universe—Thorn made out a

majestic, ancient face shadowed by a black hood. Its age put him in

mind of a fancy he had once heard someone advance, presumably in

jest—that a few men of the Dawn Civilization's twentieth century had

somehow secretly survived into the present. The stranger and Clawly

seemed to be conversing in earnest, low-pitched whispers.

Thorn's inward excitement reached a peak. It was as if his mind had

become a thin, taut membrane, against which, from the farthest reaches

of infinity, beat unknown pulses. He seemed to sense the presence of

stars beyond the stars, time-streams beyond time.

The symchromy closed. There began a long moment of complete blackness.

Then—

Thorn sensed what could only be described as something from a region

beyond the stars beyond the stars, from an existence beyond the

time-streams beyond time. A blind but purposeful fumbling that for a

moment closed on him and made him its agent.

No longer his to control, his hand stole sideways, touched some soft

fabric, brushed along it with infinite delicacy, slipped beneath a

layer of similar fabric, closed lightly on a round, hard, smooth

something about as big as a hen's egg. Then his hand came swiftly back

and thrust the something into his pocket.

Gentle groundlight flooded the hillside, though hardly touching the

black false-sky above. The audience burst into applause. Cloaks

were waved, making the hillside a crazy sea of color. Thorn blinked

stupidly. Like a flimsy but brightly-painted screen switched abruptly

into place, the scene around him cut off his vision of many-layered

infinities. And the groping power that a moment before had commanded

his movements, now vanished as suddenly as it had come, leaving him

with the realization that he had just committed an utterly unmotivated,

irrational theft.

He looked around. The old man in black was already striding toward the

amphitheater's rim, threading his way between applauding groups. Thorn

half-withdrew from his pocket the object he had stolen. It was about

two inches in diameter and of a bafflingly gray texture, neither a gem,

nor a metal, nor a stone, nor an egg, though faintly suggestive of all

four.

It would be easy to run after the man, to say, "You dropped this." But

he didn't.

The applause became patchy, erratic, surged up again as members of the

orchestra began to emerge from the pit. There was a lot of confused

activity in that direction. Shouts and laughter.

A familiar sardonic voice remarked, "Quite a gaudy show they put on.

Though perhaps a bit too close for comfort to our business of the

evening."

Thorn became aware that Clawly was studying him speculatively. He

asked, "Who was that you were talking to?"

Clawly hesitated a moment. "A psychologist I consulted some months

back when I had insomnia. You remember."

Thorn nodded vaguely, stood sunk in thought. Clawly prodded him out of

it with, "It's late. There are quite a few arrangements to check, and

we haven't much time."

Together they started up the hillside.

Especially as a pair, they presented a striking appearance—they

were such a study in similarities and contrasts. Certainly they both

seemed spiritually akin to some wilder and more troubled age than

safe, satisfied, wholesome utopia. Clawly was a small man, but dapper

and almost dancingly lithe, with gleamingly alert, subtle features.

He might have been some Borgia or Medici from that dark, glittering,

twisted core of the Dawn Civilization, when by modern standards

mankind was more than half insane. He looked like a small, red-haired,

devil-may-care satan, harnessed for good purposes.

Thorn, on the other hand, seemed like a somewhat disheveled and

reckless saint, lured by evil. His tall, gaunt frame increased the

illusion. He, too, would have fitted into that history-twisted black

dawn, perhaps as a Savonarola or da Vinci.

In that age they might have been the bitterest and most vindictive of

enemies, but it was obvious that in this they were the most unshakably

loyal of friends.

One also sensed that more than friendship linked them. Some secret,

shared purpose that demanded the utmost of their abilities and put

upon their shoulders crushing responsibilities.

They looked tired. Clawly's features were too nervously mobile, Thorn's

eyes too darkly circled, even allowing for the shadows cast by the

groundlight, which waned as the false-sky faded, became ragged, showed

the stars.

They reached the amphitheater's grassy rim, walked along a row of

neatly piled flying togs with distinctive luminescent monograms,

spotted their own. Already members of the audience were launching like

bats into the summary darkness, filling it with the faint gusty hum

of subtronic power, that basic force underlying electric, magnetic,

and gravitational phenomena, that titan, potentially earth-destroying

power, chained for human use.

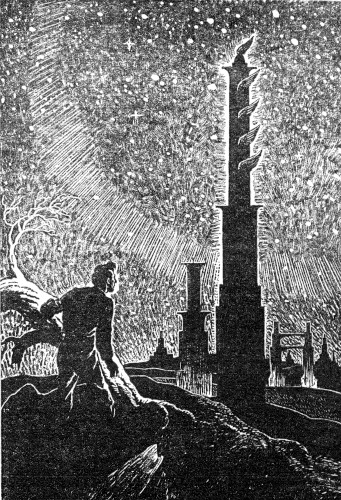

As he climbed into his flying togs, Thorn kept looking around.

False-sky and groundlight had both dissolved, opening a view to the

far horizon, although a little weather, kept electronically at bay for

the symchromy, was beginning to drift in—thin streamers of cloud. He

felt as never before a poignancy in the beauty of utopia, because he

knew as never before how near it might be to disaster, how closely it

was pressed upon by alien infinities. There was something spectral

about the grandeur of the lonely, softly-glowing skylons, lofty and

distant as mountains, thrusting up from the dark rolling countryside.

Those vertical, one-building cities of his people, focuses of communal

activity, gleaming pegs sparsely studding the whole earth—the Mauve Z

peering over the next hill, seeming to top it but actually miles away;

beyond it the Gray Twins, linked by a fantastically delicate aerial

bridge; off to the left the pearly finger of the Opal Cross; last,

farther left, thirty miles away but jutting boldly above the curve of

the earth, the mountainous Blue Lorraine—all these majestic skylons

seemed to Thorn like the last pinnacles of some fairy city engulfed

by a rising black tide. And the streams of flying men and women, with

their softly winking identification lights, no more than fireflies

doomed to drown.

His fingers adjusted the last fastening of his togs, paused there.

Clawly only said, "Well?" but there was in that one word the sense of a

leave-taking from all this beauty and comfort and safety—an ultimate

embarkation.

They pulled down their visors. From their feelings, it might have been

Mars toward which they launched themselves—a sullen ember halfway up

the sky, even now being tentatively probed by the First Interplanetary

Expedition. But their actual destination was the Opal Cross.

II.

Never before had the screams of nightmare been such a public

problem; now the wise men almost wished they could forbid sleep in the

small hours, that the shrieks of cities might less horribly disturb

the pale, pitying moon as it glimmered on green waters.

Nyarlathotep, H. P. Lovecraft.

Suppressing the fatigue that surged up in him disconcertingly, Clawly

rose to address the World Executive Committee. He found it less easy

to suppress the feeling that had in part caused the surge of fatigue:

the illusion that he was a charlatan seeking to persuade sane men of

the truth of fabricated legends of the supernatural. His smile was

characteristic of him—friendly, but faintly diabolic, mocking himself

as well as others. Then the smile faded.

He summed up, "Well, gentlemen, you've heard the experts. And by now

you've guessed why, with the exception of Thorn, they were asked

to testify separately. Also, for better or worse"—he grimaced

grayly—"you've guessed the astounding nature of the danger which Thorn

and I believe over-hangs the world. You know what we want—the means

for continuing our research on a vastly extended and accelerated scale,

along with a program of confidential detective investigation throughout

the world's citizenry. So nothing remains but to ask your verdict.

There are a few points, however, which perhaps will bear stressing."

There was noncommittal silence in the Sky Room of the Opal Cross. It

was a huge chamber and seemed no less huge because the ceiling was at

present opaque—a great gray span arching from the World Map on the

south wall to the Space Map on the north. Yet the few men gathered in

an uneven horseshoe of armchairs near the center in no way suggested

political leaders seeking a prestige-enhancing background for their

deliberations, but rather a group of ordinary men who for various

practical reasons had chosen to meet in a ballroom. Any other group

than the World Executive Committee might just as well have reserved the

Sky Room. Indeed, others had danced here earlier this night, as was

mutely testified by a scattering of lost gloves, scarves, and slippers,

along with half-emptied glasses and other flotsam of gaiety.

Yet in the faces of the gathered few there was apparent a wisdom and

a penetrating understanding and a leisurely efficiency in action that

it would have been hard to find the equal of, in any similar group

in earlier times. And a good thing, thought Clawly, for what he was

trying to convince them of was something not calculated to appeal to

the intelligence of practical administrators—it was doubtful if any

earlier culture would have granted him and Thorn any hearing at all.

He surveyed the faces unobtrusively, his dark glance flitting like a

shadow, and was relieved to note that only in Conjerly's and perhaps

Tempelmar's was a completely unfavorable reaction apparent. Firemoor,

on the contrary, registered feverish and unquestioning belief, but

that was to be expected in the volatile, easily-swayed chief of the

Extraterrestrial Service—and a man who was Clawly's admiring friend.

Firemoor was alone in this open expression of credulity. Chairman

Shielding, whose opinion mattered most, looked on the whole skeptical

and perhaps a shade disapproving; though that, fortunately, was the

heavy-set man's normal expression.

The rest, reserving judgment, were watchful and attentive. With the

unexpected exception of Thorn, who seemed scarcely to be listening,

lost in some strange fatigued abstraction since he had finished making

his report.

A still-wavering audience, Clawly decided. What he said now, and how he

said it, would count heavily.

He touched a small box. Instantly some tens of thousands of pinpricks

of green light twinkled from the World Map.

He said, "The nightmare-frequency for an average night a hundred years

ago, as extrapolated from random samplings. Each dot—a bad dream. A

dream bad enough to make the dreamer wake in fright."

Again he touched the box. The twinkling pattern changed slightly—there

were different clusterings—but the total number of pinpricks seemed

not to change.

"The same, for fifty years ago," he said. "Next—forty." Again there

was merely a slight alteration in the grouping.

"And now—thirty." This time the total number of pinpricks seemed

slightly to increase.

Clawly paused. He said, "I'd like to remind you, gentlemen, that Thorn

proved conclusively that his method of sampling was not responsible

for any changes in the frequency. He met all the objections you

raised—that his subjects were reporting their dreams more fully,

that he wasn't switching subjects often enough to avoid cultivating a

nightmare-dreaming tendency, and so on."

Once more his hand moved toward the box. "Twenty-five." This time there

was no arguing about the increase.

"Twenty."

"Fifteen."

"Ten."

"Five."

Each time the total greenness jumped, until now it was a general glow

emanating from all the continental areas. Only the seas still showed

widely scattered points, where men dreamed in supra- or sub-surface

craft, and a few heavy clusters, where ocean-based skylons rose through

the waves.

"And now, gentlemen, the present."

The evil radiance swamped the continents, reached out and touched the

faces of the armchair observers.

"There you have it, gentlemen. A restful night in utopia," said Clawly

quietly. The green glow unwholesomely emphasized his tired pallor and

the creases of strain around eyes and mouth. He went on, "Of course

it's obvious that if nightmares are as common as all that, you and

yours can hardly have escaped. Each of you knows the answer to that

question. As for myself—my nightly experiences provide one more small

confirmation of Thorn's report."

He switched off the map. The carefully noncommittal faces turned back

to him.

Clawly noted that the faint, creeping dawn-line on the World Map was

hardly two hours away from the Opal Cross. He said, "I pass over the

corroborating evidence—the slight steady decrease in average sleeping

time, the increase in day sleeping and nocturnal social activity, the

unprecedented growth of art and fiction dealing with supernatural

terror, and so on—in order to emphasize as strongly as possible

Thorn's secondary discovery: the similarity between the nightmare

landscapes of his dreamers. A similarity so astonishing that, to me,

the wonder is that it wasn't noticed sooner, though of course Thorn

wasn't looking for it and he tells me that most of his earlier subjects

were unable, or disinclined, to describe in detail the landscapes

of their nightmares." He looked around. "Frankly, that similarity

is unbelievable. I don't think even Thorn did full justice to it in

the time he had for his report—you'd have to visit his offices,

see his charts and dream-sketches, inspect his monumental tables of

correlation. Think: hundreds of dreamers, to take only Thorn's samples,

thousands of miles apart, and all of them dreaming—not the same

nightmare, which might be explained by assuming telepathy or some

subtle form of mass suggestion—but nightmares with the same landscape,

the same general landscape. As if each dreamer were looking through a

different window at a consistently distorted version of our own world.

A dream world so real that when I recently suggested to Thorn he try to

make a map of it, he did not dismiss my notion as nonsensical."

The absence of a stir among his listeners was more impressive than any

stir could have been. Clawly noted that Conjerly's frown had deepened,

become almost angry. He seemed about to speak, when Tempelmar casually

forestalled him.

"I don't think telepathy can be counted out as an explanation,"

said the tall, long-featured, sleepy-eyed man. "It's still a purely

hypothetic field—we don't know how it would operate. And there may

have been contacts between Thorn's subjects that he didn't know about.

They may have told each other their nightmares and so started a train

of suggestion."

"I don't believe so," said Clawly slowly. "His precautions were

thorough. Moreover, it wouldn't fit with the reluctance of the dreamers

to describe their nightmares."

"Also," Tempelmar continued, "we still aren't a step nearer the

underlying cause of the phenomenon. It might be anything—for instance,

some unpredictable physiological effect of subtronic power, since it

came into use about thirty years ago."

"Precisely," said Clawly. "And so for the present we'll leave it

at that—vastly more frequent nightmares with strangely similar

landscapes, cause unknown—while I"—he again gauged the position of

the dawn-line—"while I hurry on to those matters which I consider the

core of our case: the incidence of cryptic amnesia and delusions of

nonrecognition. The latter first."

Again Conjerly seemed about to interrupt, and again something stopped

him. Clawly got the impression it was a slight deterring movement from

Tempelmar.

He touched the box. Some hundreds of yellow dots appeared on the World

Map, a considerable portion of them in close clusters of two and three.

He said, "This time, remember, we can't go back any fifty years. These

are such recent matters that there wasn't any hint of them even in last

year's Report on the Psychological State of the World. As the experts

agreed, we are dealing with an entirely new kind of mental disturbance.

At least, no cases can be established prior to the last two years,

which is the period covered by this projection."

He looked toward the map. "Each yellow dot is a case of delusions of

nonrecognition. An otherwise normal individual fails to recognize a

family member or friend, maintains in the face of all evidence that

he is an alien and impostor—a frequent accusation, quite baseless,

is that his place has been taken by an unknown identical twin. This

delusion persists, attended by emotional disturbances of such magnitude

that the sufferer seeks the services of a psychiatrist—in those cases

we know about. With the psychiatrist's assistance, one of

two adjustments is achieved: the delusions fade and the avowed alien

is accepted as the true individual, or they persist and there is a

separation—where husband and wife are involved, a divorce. In either

case, the sufferer recovers completely.

"And now—cryptic amnesia. For a reason that will soon become apparent,

I'll first switch off the other projection."

The yellow dots vanished, and in their place glowed a somewhat smaller

number of violet pinpoints. These showed no tendency to form clusters.

"It is called cryptic, I'll remind you, because the victim makes a very

determined and intelligently executed effort to conceal his memory

lapse—frequently shutting himself up for several days on some pretext

and feverishly studying all materials and documents relating to himself

he can lay hands on. Undoubtedly sometimes he succeeds. The cases we

hear about are those in which he makes such major slips—as being

mistaken as to what his business is, who he is married to, who his

friends are, what is going on in the world—that he is forced, against

his will, to go to a psychiatrist. Whereupon, realizing that his

efforts have failed, he generally confesses his amnesia, but is unable

to offer any information as to its cause, or any convincing explanation

of his attempt at concealment. Thereafter, readjustment is rapid."

He looked around. "And now, gentlemen, a matter which the experts

didn't bring out, because I arranged it that way. I have saved it

in order to impress it upon your minds as forcibly as possible—the

correlation between cryptic amnesia and delusions of nonrecognition."

He paused with his hand near the box, aware that there was something

of the conjurer about his movements and trying to minimize it. "I'm

going to switch on both projections at once. Where cases of cryptic

amnesia and delusions of nonrecognition coincide—I mean, where it

is the cryptic amnesiac about whom the other person or persons had

delusions of nonrecognition—the dots will likewise coincide; and

you know what happens when violet and yellow light mix. I'll remind

you that in ordinary cases of amnesia there are no delusions of

nonrecognition—family and friends are aware of the victim's memory

lapse, but they do not mistake him for a stranger."

His hand moved. Except for a sprinkling of yellow, the dots that glowed

on the map were pure white.

"Complementary colors," said Clawly quietly. "The yellow has blanked

out all the violet. In some cases one violet has accounted for a

cluster of yellows—where more than one individual had delusions of

nonrecognition about the same cryptic amnesiac. Except for the surplus

cases of nonrecognition—which almost certainly correspond to cases of

successfully concealed cryptic amnesia—the nonrecognitions and cryptic

amnesias are shown to be dual manifestations of a single underlying

phenomenon."

He paused. The tension in the Sky Room deepened. He leaned forward. "It

is that underlying phenomenon, gentlemen, which I believe constitutes a

threat to the security of the world, and demands the most immediate and

thorough-going investigation. Though staggering, the implications are

obvious."

The tautness continued, but slowly Conjerly got to his feet. His

compact, stubby frame, bald bullet-head, and uncompromisingly impassive

features were in striking contrast with Clawly's mobile, half-haggard,

debonair visage.

Leashed anger deepened Conjerly's voice, enhanced its authority.

"We have come a long way from the Dawn Era, gentlemen. One might

think we would never again have to grapple with civilization's old

enemy superstition. But I am forced to that regretful conclusion when

I hear this gentleman, to whom we have granted the privilege of an

audience, advancing theories of demoniac possession to explain cases

of amnesia and nonrecognition." He looked at Clawly. "Unless I wholly

misunderstood?"

Clawly decisively shook his head. "You didn't. It is my contention—I

might as well put it in plain words—that alien minds are displacing

the minds of our citizens, that they are infiltering Earth, seeking

to gain a foothold here. As to what minds they are, where they come

from—I can't answer that, except to remind you that Thorn's studies

of dream landscapes hint at a world strangely like our own, though

strangely distorted. But the secrecy of the invaders implies that their

purpose is hostile—at best, suspect. And I need not remind you that,

in this age of subtronic power, the presence of even a tiny hostile

group could become a threat to Earth's very existence."

Slowly Conjerly clenched his stub fingers, unclenched them. When he

spoke, it was as if he were reciting a creed.

"Materialism is our bedrock, gentlemen—the firm belief that every

phenomenon must have a real existence and a real cause. It has made

possible science technology, unbiased self-understanding. I am

open-minded. I will go as far as any in granting a hearing to new

theories. But when those theories are a revival of the oldest and most

ignorant superstitions, when this gentleman seeks to frighten us with

nightmares and tales of evil spirits stealing human bodies, when he

asks us on this evidence to institute a gigantic witch-hunt, when he

raises the old bogey of subtronic power breaking loose, when he brings

in a colleague"—he glared at Thorn—"who takes seriously to the idea

of surveying dream worlds with transit and theodolite—then I say,

gentlemen, that if we yield to such suggestions, we might as well throw

materialism overboard and, as for safeguarding the future of mankind,

ask the advice of fortunetellers!"

At the last word Clawly started, recovered himself. He dared not look

around to see if anyone had noticed.

The anger in Conjerly's voice strained at its leash, threatened to

break it.

"I presume, sir, that your confidential investigators will go out with

wolfsbane to test for werewolves, garlic to uncover vampires, and cross

and holy water to exorcise demons!"

"They will go out with nothing but open minds," Clawly answered quietly.

Conjerly breathed deeply, his face reddened slightly, he squared

himself for a fresh and more uncompromising assault. But just at that

moment Tempelmar eased himself out of his chair. As if by accident, his

elbow brushed Conjerly's.

"No need to quarrel," Tempelmar drawled pleasantly, "though our

visitor's suggestions do sound rather peculiar to minds tempered to a

realistic materialism. Nevertheless, it is our duty to safeguard the

world from any real dangers, no matter how improbable or remote. So,

considering the evidence, we must not pass lightly over our visitor's

theory that alien minds are usurping those of Earth—at least not until

there has been an opportunity to advance alternate theories."

"Alternate theories have been advanced, tested, and discarded,"

said Clawly sharply.

"Of course," Tempelmar agreed smilingly. "But in science that's a

process that never quite ends, isn't it?"

He sat down, Conjerly following suit as if drawn. Clawly was irascibly

conscious of having got the worst of the interchange—and the lanky,

sleepy-eyed Tempelmar's quiet skepticism had been more damaging than

Conjerly's blunt opposition, though both had told. He felt, emanating

from the two of them, a weight of personal hostility that bothered and

oppressed him. For a moment they seemed like utter strangers.

He was conscious of standing too much alone. In every face he could

suddenly see skepticism. Shielding was the worst—his expression

had become that of a man who suddenly sees through the tricks of a

sleight-of-hand artist masquerading as a true magician. And Thorn, who

should have been mentally at his side, lending him support, was sunk in

some strange reverie.

He realized that even in his own mind there was a growing doubt of the

things he was saying.

Then, utterly unexpectedly, adding immeasurably to his dismay, Thorn

got up, and without even a muttered excuse to the men beside him,

left the room. He moved a little stiffly, like a sleepwalker. Several

glanced after him curiously. Conjerly nodded. Tempelmar smiled.

Clawly noted it. He rallied himself. He said, "Well, gentlemen?"

III.

But who will reveal to our waking ken

The forms that swim and the shapes that creep

Under the waters of sleep?

The Marshes of Glynn, Sidney Lanier.

Like a dreamer who falls head-foremost for giddy miles and then is

wafted to a stop as gently as a leaf, Thorn plunged down the main

vertical levitator of the Opal Cross and swam out of it at ground

level, before its descent into the half mile of basements. At this

hour the great gravity-less tube was relatively empty, except for the

ceaseless silent plunge and ascent of the graduated subtronic currents

and the air they swept along. There were a few other down-and-up

swimmers—distant leaflike swirls of color afloat in the contracting

white perspective of the tube—but, like a dreamer, Thorn did not seem

to take note of them.

Another levitating current carried him along some hundred yards of

mural-faced corridor to one of the pedestrian entrances of the Opal

Cross. A group of revelers stopped their crazy, squealing dance in the

current to watch him. They looked like figures swum out of the potently

realistic murals—but with a more hectic, troubled gaiety on their

faces. There was something about the way he plunged past them unseeing,

his sleepwalker's eyes fixed on something a dozen yards ahead, that

awakened unpleasant personal thoughts and spoiled their feverish

fun-making.

The pedestrian entrance was really a city-limits. Here the one-building

metropolis ended, and there began the horizontal miles of half-wild

countryside, dark as the ancient past, trackless and roadless in the

main, dotted in many areas with small private dwellings, but liberally

brushed with forests.

A pair of lovers on the terrace, pausing for a kiss as they adjusted

their flying togs, broke off to look curiously after Thorn as he

hurried down the ramp and across the close-cropped lawn, following one

of the palely-glowing pathways. The up-slanting pathlight, throwing

into gaunt relief his angular cheek-bones and chin, made him resemble

some ancient pilgrim or crusader in the grip of a religious compulsion.

Then the forest had swallowed him up.

A strange mixture of trance and willfullness, of dream and waking,

of aimless wandering and purposeful tramping, gripped Thorn as he

adventured down that black-fringed ghost-trail. Odd memories of

childhood, of old hopes and desires, of student days with Clawly,

of his work and the bewildering speculations it had led to, drifted

across his mind, poignant but meaningless. Among these, but drained of

significance, like the background of a dream, there was a lingering

picture of the scene he had left behind him in the Sky Room. He was

conscious of somehow having deserted a friend, abandoned a world,

betrayed a great purpose—but it was a blurred consciousness and he had

forgotten what the great purpose was.

Nothing seemed to matter any longer but the impulse pulling him

forward, the sense of an unknown but definite destination.

He had the feeling that if he looked long enough at that receding,

beckoning point a dozen yards ahead, something would grow there.

The forest path was narrow and twisting. Its faint glow silhouetted

weeds and brambles partly over-growing it. His hands pushed aside

encroaching twigs.

He felt something tugging at his mind from ahead, as if there were

other avenues leading to his subconscious than that which went through

his consciousness. As if his subconscious were the core of two or more

minds, of which his was the only one.

Under the influence of that tugging, imagination awoke.

Instantly it began to recreate the world of his nightmares. The

world which had obscurely dominated his life and turned him to

dream-research, where he had found similar nightmares. The world

where danger lay. The blue-litten world in which a mushroom growth of

ugly squat buildings, like the factories and tenements and barracks

of ancient times, blotched the utopian countryside, and along whose

sluice-like avenues great crowds of people ceaselessly drifted, unhappy

but unable to rest—among them that other, dream Thorn, who hated and

envied him, deluged him with an almost unbearable sense of guilt.

For almost as long as he could remember, that dream Thorn had tainted

his life—the specter at his feasts, the suppliant at his gates, the

eternal accuser in the courts of inmost thought—drifting phantom-wise

across his days, rising up starkly real and terrible in his nights.

During the long, busy holiday of youth, when every day had been a

new adventure and every thought a revelation, that dream Thorn had

been painfully discovering the meaning of oppression and fear, had

been security swept away and parents exiled, had attended schools in

which knowledge was forbidden and all a man learned was his place.

When he was discovering happiness and love, that dream Thorn had been

rebelliously grieving for a young wife snatched away from him forever

because of some autocratic government's arbitrary decrees. And while

he was accomplishing his life's work, building new knowledge stone by

stone, that dream Thorn had toiled monotonously at meaningless jobs,

slunk away to brood and plot with others of his kind, been harried by

a fiendishly efficient secret police, become a hater and a killer.

Day by day, month by month, year by year, the dark-stranded dream life

had paralleled his own.

He knew the other Thorn's emotions almost better than his own, but the

actual conditions and specific details of the dream Thorn's life were

blurred and confused in a characteristically dreamlike fashion. It

was as if he were dreaming that other Thorn's dreams—while, by some

devilish exchange, that other Thorn dreamed his dreams and hated him

for his good fortune.

A sense of guilt toward his dream-twin was the dominant fact in Thorn's

inner life.

And now, pushing through the forest, he began to fancy that he could

see something at the receding focus of his vision a dozen yards ahead,

something that kept flickering and fading, so that he could scarcely

be sure that he saw it, and that yet seemed an embodiment of all the

unseen forces dragging him along—a pale, wraithlike face, horribly

like his own.

The sense of a destination grew stronger and more urgent. The mile

wall of the Opal Cross, a pale cataract of stone glimpsed now and then

through overhanging branches, still seemed to rise almost at his heels,

creating the maddening illusion that he was making no progress. The

wraith-face blacked out. He began to run.

Twigs lashed him. A root caught at his foot. He stumbled, checked

himself, and went on more slowly, relieved to find that he could at

least govern the rate of his progress.

The forces tugging at him were both like and infinitely unlike those

which had for a moment controlled his movements at the symchromy.

Whereas those had seemed to have a wholly alien source, these seemed to

have come from a single human mind.

He felt in his pocket for the object he had stolen from Clawly's

mysterious confidant. He could not see much of its color now, but that

made its baffling texture stand out. It seemed to have a little more

inertia than its weight would account for. He was certain he had never

touched anything quite like it before.

He couldn't say where the notion came from, but he suddenly found

himself wondering if the thing could be a single molecule. Fantastic!

And yet, was there anything to absolutely prevent atoms from

assembling, or being assembled, in such a giant structure?

Such a molecule would have more atoms than the universe had suns.

Oversize molecules were the keys of life—the hormones, the activators,

the carriers of heredity. What doors might not a supergiant molecule

unlock?

The merest fancy—yet frightening. He started to throw the thing away,

but instead tucked it back in his pocket.

There was a rush in the leaves. A large cat paused for an instant in

the pathlight to snarl and stare at him. Such cats were common pets,

for centuries bred for intelligence and for centuries tame. Yet now, on

the prowl, it seemed all wild—with an added, evil insight gained from

long association with man.

The path branched. He took a sharp turn, picking his way over bulbous

roots. The pathlight grew dim and diffuse, its substance dissolved and

spread by erosion. At places the vegetation had absorbed some of the

luminescence. Leaves and stems glowed faintly.

But beyond, on either side, the forest was a black, choked infinity.

It had come inscrutably alive.

The sense of a thousand infinities pressing upon him, experienced

briefly at the Yggdrasil, now returned with redoubled force.

The Yggdrasil was true. Reality was not what it seemed on the surface.

It had many roots, some strong and true, some twisted and gnarled,

nourished in many worlds.

He quickened his pace. Again something seemed to be growing at the

focus of his vision—a flitting, pulsating, bluish glow. It was like

the Yggdrasil's Nidhogg motif. Nidhogg, the worm gnawing ceaselessly at

the root of the tree of life that goes down to hell. It droned against

his vision—an unshakable color-tune.

Then, gradually, it became a face. His own face, but seared by

unfamiliar emotions, haggard with unknown miseries, hard, vengeful,

accusing—the face of the dream Thorn, beckoning, commanding, luring

him toward some unknown destination in the maze of unknown, unseen

worlds.

With a sob of courage and fear, he plunged toward it.

He must come to grips with that other Thorn, settle accounts with him,

even the balance of pleasure and pain between them, right the wrong of

their unequal lives. For in some sense he must be that other

Thorn, and that other Thorn must be he. And a man could not be untrue

to himself.

The wraithlike face receded as swiftly as he advanced.

His progress through the forest became a nightmarish running of the

gauntlet, through a double row of giant black trees that slashed him

with their branches.

The face kept always a few yards ahead.

Fear came, but too late—he could not stop.

The dreamy veils that had been drawn across his thoughts and memories

during the first stages of his flight from the Opal Cross, were torn

away. He realized that what was happening to him was the same thing

that had happened to hundreds of other individuals. He realized that an

alien mind was displacing his own, that another invader and potential

cryptic amnesiac was gaining a foothold on Earth.

The thought hit him hard that he was deserting Clawly, leaving the

whole world in the lurch.

But he was only a will-less thing that ran with outclutched hands.

Once he crossed a bare hilltop and for a moment caught a glimpse of the

lonely glowing skylons—the Blue Lorraine, the Gray Twins, the Myrtle

Y—but distant beyond reach, like a farewell.

He was near the end of his strength.

The sense of a destination grew overpoweringly strong.

Now it was something just around the next turn in the path.

He plunged through a giddy stretch of darkness thick as ink—and came

to a desperate halt, digging in his heels, flailing his arms.

From somewhere, perhaps from deep within his own mind, came a faint

echo of mocking laughter.

IV.

If you can look into the seeds of time,

And say which grain will grow and which will not—

Like a mote in the grip of an intangible whirlwind, Clawly whipped

through the gray dawn on a steady surge of subtronic power toward the

upper levels of the Blue Lorraine. The brighter stars, and Mars, were

winking out. Through the visor of his flying togs the rushing air sent

a chill to which his blood could not quite respond. He should be home,

recuperating from defeat, planning new lines of attack. He should be

letting fatigue poisons drain normally from his plasma, instead of

knocking them out with stimulol. He should be giving his thoughts a

chance to unwind. Or he should have given way to lurking apprehensions

and be making a frantic search for Thorn. But the itch of a larger

worry was upon him, and until he had done a certain thing, he could not

pursue personal interests, or rest.

With Thorn gone, his rebuff in the Sky Room loomed as a black and

paralyzingly insurmountable obstacle that grew momently higher. They

were lucky, he told himself, not to have had their present research

funds curtailed—let alone having them increased, or being given a

large staff of assistants, or being granted access to the closely

guarded files of confidential information on cryptic amnesiacs and

other citizens. Any earlier culture would probably have forbidden their

research entirely, as a menace to the mental stability of the public.

Only an almost fetishlike reverence for individual liberty and the

inviolability of personal pursuits, had saved them.

The Committee's adverse decision had even shaken his own beliefs. He

felt himself a puny little man, beset by uncertainties and doubts,

quite incompetent to protect the world from dangers as shadowy, vast,

and inscrutable as the gloom-drenched woodlands a mile below.

Why the devil had Thorn left the meeting like that, of necessity

creating a bad impression? Surely he couldn't have given way to any

luring hypnotic impulse—he of all men ought to know the danger of

that. Still, there had been that unpleasant suggestion of sleepwalking

in his departure—an impression that Clawly's memory kept magnifying.

And Thorn was a strange fellow. After all these years, Clawly still

found him unpredictable. Thorn had a spiritual recklessness, an urge

to plumb all mental deeps. And God knows there were deeps enough

for plumbing these days, if one were foolish. Clawly felt them in

himself—the faint touch of a darker, less pleasant version of his own

personality, against which he must keep constantly on guard.

If he had let something happen to Thorn—!

A variation in the terrestrial magnetic field, not responded to soon

enough, sent him spinning sideways a dozen yards, forced his attention

back on his trip.

He wondered if he had managed to slip away as unobtrusively as he had

thought. A few of the committee members had wanted to talk. Firemoor,

who had voted against the others and supported Clawly's views rather

too excitedly, had been particularly insistent. But he had managed

to put them off. Still, what if he were followed? Surely Conjerly's

reference to "fortunetellers" had been mere chance, although it had

given him a nasty turn. But if Conjerly and Tempelmar should find out

where he was going now—What a handle that would give them against him!

It would be wiser to drop the whole business, at least for a time.

No use. The vice of the thing—if vice it be—was in his blood. The

Blue Lorraine drew him as a magnet flicks up a grain of iron.

A host of images fought for possession of his tired mind, as he

plunged through thin streamers of paling cloud. Green dots on the World

Map. The greens and blues of the Yggdrasil—and in what nightmare

worlds had Hoderson found his inspiration? The blue-tinted sketches one

of Thorn's dreamers had made of the world of his nightmares. A sallow

image of Thorn's face altered and drawn by pain, such an image as might

float into the mind of one who watches too long by a sickbed. The looks

on the faces of Conjerly and Tempelmar—that fleeting impression of a

hostile strangeness. The hint of a dark alien presence in the depths of

his own mind.

The Blue Lorraine grew gigantic, loomed as a vast, shadow-girt cliff,

its topmost pinnacles white with frost although the night below had

been summery. There were already signs of a new day beginning. Here

and there freighters clung like beetles to the wall, discharging or

receiving cargo through unseen ports. Some distance below a stream of

foodstuffs for the great dining halls, partly packaged, partly not,

was coming in on a subtronic current. Off to one side an attendant

shepherded a small swarm of arriving schoolchildren, although it was

too early yet for the big crowds.

Clawly swooped to a landing stage, hovered for a moment like a bird,

then dropped. In the ante-room he and another early arriver helped each

other remove and check their flying togs.

He was breathing hard, there was a deafness and a ringing in his ears,

he rubbed his chilled fingers. He should not have made such a steep

and swift ascent. It would have been easier to land at a lower stage

and come up by levitator. But this way was more satisfying to his

impatience. And there was less chance of someone following him unseen.

A levitating current wafted him down a quarter mile of mainstem

corridor to the district of the psychologists. From there he walked.

He looked around uneasily. Only now did real doubt hit him. What

if Conjerly were right? What if he were merely dragging up ancient

superstitions, foisting them on a group of overspecialized experts,

Thorn included? What if the world-threat he had tried to sell to

the World Executive Committee were just so much morbid nonsense,

elaborately bastioned by a vast array of misinterpreted evidence? What

if the darker, crueler, deviltry-loving side of his mind were more in

control than he realized? He felt uncomfortably like a charlatan, a

mountebank trying to pipe the whole world down a sinister side street,

a chaos-loving jester seeking to perpetrate a vast and unpleasant hoax.

It was all such a crazy business, with origins far more dubious than he

had dared reveal even to Thorn, from whom he had no other secrets. Best

back down now, at least quit stirring up any more dark currents.

But the other urge was irresistible. There were things he had to know,

no matter the way of knowing.

Stealing himself, he paraphrased Conjerly. "If the evidence seems

to point that way, if the safety of mankind seems to demand it,

then I will throw materialism overboard and ask the advice of

fortunetellers!"

He stopped. A door faced him. Abruptly it was a doorway. He went in,

approached the desk and the motionless, black-robed figure behind it.

As always, there was in Oktav's face that overpowering suggestion of

age—age far greater than could be accounted for by filmy white hair,

sunken cheeks, skin tight-drawn and wrinkle-etched. Unwilled, Clawly's

thoughts turned toward the Dawn Civilization with its knights in armor

and aircraft winged like birds, its whispered tales of elixirs of

eternal life—and toward that oddly long-lived superstition, rumor,

hallucination, that men clad in the antique garments of the Late Middle

Dawn Civilization occasionally appeared on Earth for brief periods at

remote places.

Oktav's garb, at any rate, was just an ordinary houserobe. But in their

wrinkle-meshed orbits, his eyes seemed to burn with the hopes and fears

and sorrows of centuries. They took no note of Clawly as he edged into

a chair.

"I see suspense and controversy," intoned the seer abruptly. "All night

it has surged around you. It regards that matter whereof we spoke at

the Yggdrasil. I see others doubting and you seeking to persuade them.

I see two in particular in grim opposition to you, but I cannot see

their minds or motives. I see you in the end losing your grip, partly

because of a friend's seeming desertion, and going down in defeat."

Of course, thought Clawly, he could learn all this by fairly simple

spying. Still, it impressed him, as it always had since he first

chanced—But was it wholly chance?—to contact Oktav in the guise of an

ordinary psychologist.

Not looking at the seer, with a shyness he showed toward no one else,

Clawly asked, "What about the world's future? Do you see anything more

there?"

There was a faint drumming in the seer's voice. "Only thickening

dreams, more alien spirits stalking the world in human mask, doom

overhanging, great claws readying to pounce—but whence or when I

cannot tell, only that your recent effort to convince others of the

danger has brought the danger closer."

Clawly shivered. Then he sat straighter. He was no longer shy.

Docketing the question about Thorn that was pushing at his lips, he

said, "Look, Oktav, I've got to know more. It's obvious that you're

hiding things from me. If I map the best course I can from the hints

you give me, and then you tell me that it is the wrong course, you

tie my hands. For the good of mankind, you've got to describe the

overhanging danger more definitely."

"And bring down upon us forces that will destroy us both?" The seer's

eyes stabbed at him. "There are worlds within worlds, wheels within

wheels. Already I have told you too much for our safety. Moreover,

there are things I honestly do not know, things hidden even from the

Great Experimenters—and my guesses might be worse than yours."

Taut with a sense of feverish unreality, Clawly's mind wandered.

What was Oktav—what lay behind that ancient mask? Were all faces

only masks? What lay behind Conjerly's and Tempelmar's? Thorn's?

His own? Could your own mind be a mask, too, hiding things from

your own consciousness? What was the world—this brief masquerade

of inexplicable events, flaring up from the future to be instantly

extinguished in the past?

"But then what am I to do, Oktav?" he heard his tired voice ask.

The seer replied, "I have told you before. Prepare your world for any

eventuality. Arm it. Mobilize it. Do not let it wait supine for the

hunter."

"But how can I, Oktav? My request for a mere program of investigation

was balked. How can I ask the world to arm—for no reason?"

The seer paused. When he finally answered there drummed in his voice,

stronger than ever, the bitter wisdom of centuries.

"Then you must give it a reason. Always governments have provided

appropriate motives for action, when the real motives would be

unpalatable to the many, or beyond their belief. You must extemporize

a danger that fits the trend of their short-range thinking. Now let me

see—Mars—"

There was a slight sound. The seer wheeled around with a serpentine

rapidity, one skinny hand plunged in the breast of his robe. It fumbled

wildly, agitating the black, weightless fabric, then came out empty. A

look of extreme consternation contorted his features.

Clawly's eyes shifted with his to the inner doorway.

The figure stayed there peering at Oktav for only a moment. Then, with

an impatient, peremptory flirt of its head, it turned and moved out of

sight. But it was indelibly etched, down to the very last detail, on

Clawly's panic-shaken vision.

Most immediately frightening was the impression of age—age greater

than Oktav's, although, or perhaps because, the man's physical

appearance was that of thirty-odd, with dark hair, low forehead,

vigorous jaw. But in the eyes, in the general expression—centuries of

knowledge. Yet knowledge without wisdom, or with only a narrow-minded,

puritanic, unsympathetic, overweening simulacrum of wisdom. A

disturbing blend of unconscious ignorance and consciousness of power.

The animal man turned god, without transfiguration.

But the most lingering impression, oddly repellent, was of its

clothing. Crampingly unwieldly upper and nether garments of

tight-woven, compressed, tortured animal-hair, fastened by bits of

bone or horn. The upper garment had an underduplicate of some sort of

bleached vegetable fiber, confined at the throat by two devices—one a

tightly knotted scarf of crudely woven and colored insect spinnings,

the other a high and unyielding white neckband, either of the same

fiber as the shirt, glazed and stiffened, or some primitive plastic.

It gave Clawly an added, anti-climactic start to realize that the

clothing of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which he had

seen pictured in history albums, would have just this appearance, if

actually prepared according to the ancient processes and worn by a

human being.

Without explanation, Oktav rose and moved toward the inner doorway. His

hand fumbled again in his robe, but it was merely an idle repetition

of the earlier gesture. In the last glimpse he had of his face, Clawly

saw continued consternation, frantic memory-searching, and the frozen

intentness of a competent mind scanning every possible avenue of escape

from a deadly trap.

Oktav went through the doorway.

There was no sound.

Clawly waited.

Time spun on. Clawly shifted his position, caught himself, coughed,

waited, coughed again, got up, moved toward the inner doorway, came

back and sat down.

There was time, too much time. Time to think again and again of that

odd superstition about fleeting appearances of men in Dawn-Civilization

garb. Time to make a thousand nightmarish deductions from the age in

Oktav's, and that other's, eyes.

Finally he got up and walked to the inner doorway.

There was a tiny unfurnished room, without windows or another door, the

typical secondary compartment of offices like this. Its walls were bare

and seamless.

There was no one.

V.

... and still remoter spaces where only a stirring in vague

blacknesses had told of the presence of consciousness and will.

The Haunter of the Dark, Howard Phillips Lovecraft.

With a sickening ultimate plunge, that seemed to plumb in instants

distances greater than the diameter of the cosmos—a plunge in which

more than flesh and bones were stripped away, transformed—Oktav

followed his summoner into a region of not only visual night.

Here in the Zone, outside the bubble of space-time, on the borders of

eternity, even the atoms were still. Only thought moved—but thought

powered beyond description or belief, thought that could make or mar

universes, thought not unbefitting gods.

Most strange, then, to realize that it was human thought, with all its

homely biases and foibles. Like finding, on another planet in another

universe, a peasant's cottage with smoke wreathing above the thatched

roof and an axe wedged in a half-chopped log.

Mice scurrying at midnight in a vast cathedral—and the faint

suggestion that the cathedral might not be otherwise wholly empty.

Oktav, or that which had been Oktav, oriented itself—himself—making

use of the sole means of perception that functioned in the Zone. It was

most akin to touch, but touch strangely extended and sensitive only to

projected thought or processes akin to thought.

Groping like a man shut in an infinite closet, Oktav felt the eternal

hum of the Probability Engine, the lesser hum of the seven unlocked

talismans. He felt the seven human minds in their stations around the

engine, felt six of them stiffen with cold disapproval as Ters made

report. Then he took his own station, the last and eighth.

Ters concluded.

Prim thought, "We summoned you, Oktav, to hear your explanation of

certain highly questionable activities in which you have recently

indulged—only to learn that you have additionally committed an act

of unprecedented negligence. Never before has a talisman been lost.

And only twice has it been necessary to make an expedition to recover

one—when its possessor met accidental death in a space-time world.

How can you have permitted this to happen, since a talisman gives

infallible warning if it is in any way spatially or temporarily parted

from its owner?"

"I am myself deeply puzzled," Oktav admitted. "Some obscure influence

must have been operative, inhibiting the warning or closing my mind to

it. I did not become aware of the loss until I was summoned. However,

casting my mind back across the last Earth-day's events, I believe I

can now discern the identity of the individual into whose hands it

fell—or who stole it."

"Was the talisman inert at the time?" thought Prim quickly.

"Yes," thought Oktav. "A Key-idea known only to myself would be

necessary to unlock its powers."

"That is one small point in your favor," thought Prim.

"I am gravely at fault," thought Oktav, "but it can easily be mended.

Lend me another talisman and I will return to the world and recover it."

"It will not be permitted," thought Prim. "You have already spent too

much time in the world, Oktav. Although you are the youngest of us,

your body is senile."

Before he could check himself, or at least avoid projection, Oktav

thought, "Yes, and by so doing I have learned much that you, in your

snug retreat, would do well to become aware of."

"The world and its emotions have corrupted you," thought Prim. "And

that brings me to the second and major point of our complaint."

Oktav felt the seven minds converge hostilely upon him. Careful to mask

his ideational processes, Oktav probed the others for possible sympathy

or weakness. Lack of a talisman put him at a great disadvantage. His

hopes fell.

Prim thought, "It has come to our attention that you have been telling

secrets. Moved by some corrupt emotionality, and under the astounding

primitive guise of fortunetelling, you have been disbursing forbidden

knowledge—cloudily perhaps, but none the less unequivocally—to

earthlings of the main-trunk world."

"I do not deny it," thought Oktav, crossing his Rubicon. "The

main-trunk world needs to know more. It has been your spoiled

brat. And as often happens to a spoiled brat, you now push it,

unprepared and unaided, into a dubious future."

Prim's answering thought, amplified by his talisman, thundered in the

measureless dark. "We are the best judges of what is good for

the world. Our minds are dedicated far more selflessly than yours to

the world's welfare, and we have chosen the only sound scientific

method for insuring its continued and ultimate happiness. One of the

unalterable conditions of that method is that no Earthling have the

slightest concrete hint of our activities. Has your mind departed so

far from scientific clarity—influenced perhaps by bodily decay due to

injudicious exposure to space-time—that I must recount to you our

purpose and our rules?"

The darkness pulsed. Oktav projected no answering thought. Prim

continued, thinking in a careful step-by-step way, as if for a child.

"No scientific experiment is possible without controls—set-ups in

which the conditions are unaltered, as a comparison, in order to

gauge the exact effects of the alteration. There is, under natural

conditions, only one world. Hence no experiments can be performed

upon it. One can never test scientifically which form of social

organization, government, and so forth, is best for it. But the

creation of alternate worlds by the Probability Engine changes all

that."

Prim's thought beat at Oktav.

"Can it be that the underlying logic of our procedure has somehow

always escaped you? From our vantage point we observe the world as

it rides into the cone of the future—a cone that always narrows

towards the present, because in the remote future there are many major

possibilities still realizable, in the near future only a relative

few. We note the approach of crucial epochs, when the world must

make some great choice, as between democracy and totalitarianism,

managerialism and servicism, benevolent elitism and enforced equalism

and so on. Then, carefully choosing the right moment and focussing the

Probability Engine chiefly upon the minds of the world's leaders, we

widen the cone of the future. Two or more major possibilities are then

realized instead of just one. Time is bifurcated, or trifurcated. We

have alternate worlds, at first containing many objects and people

in common, but diverging more and more—bifurcating more and more

completely—as the consequences of the alternate decisions make

themselves felt."

"I criticize," thought Oktav, plunging into uncharted waters. "You

are thinking in generalities. You are personifying the world, and

forgetting that major possibilities are merely an accumulation of minor

ones. I do not believe that the distinction between the two major

alternate possibilities in a bifurcation is at all clear-cut."

The idea was too novel to make any immediate impression, except that

Oktav's mind was indeed being hazy and disordered. As if Oktav had not

thought, Prim continued, "For example, we last split the time-stream

thirty Earth-years ago. Discovery of subtronic power had provided the

world with a practically unlimited source of space-time energy. The

benevolent elite governing the world was faced with three clear-cut

alternatives: It could suppress the discovery completely, killing its

inventors. It could keep it a Party secret, make it a Party asset.

It could impart it to the world at large, which would destroy the

authority of the Party and be tantamount to dissolving it, since it

would put into the hands of any person, or at least any small group

of persons, the power to destroy the world. In a natural state, only

one of these possibilities could be realized. Earth would only have

one chance in three of guessing right. As we arranged it, all three

possibilities were realized. A few years' continued observation

sufficed to show us that the third alternative—that of making

subtronic power common property—was the right one. The other two had

already resulted in untold unendurable miseries and horrors."

"Yes, the botched worlds," Oktav interrupted bitterly. "How many of

them have there been, Prim? How many, since the beginning?"

"In creating the best of all possible worlds, we of necessity also

created the worst," Prim replied with a strained patience.

"Yes—worlds of horror that might have never been, had you not insisted

on materializing all the possibilities, good and evil lurking in men's

minds. If you had not interfered, man still might have achieved that

best world—suppressing the evil possibilities."

"Do you suggest that we should leave all to chance?" Prim exploded

angrily. "Become fatalists? We, who are masters of fate?"

"And then," Oktav continued, brushing aside the interruption, "having

created those worst or near-worlds—but still human, living ones, with

happiness as well as horror in them, populated by individuals honestly

striving to make the best of bad guesses—you destroy them."

"Of course!" Prim thought back in righteous indignation. "As soon as we

were sure they were the less desirable alternatives, we put them out

of their misery."

"Yes." Oktav's bitterness was like an acid drench. "Drowning the

unwanted kittens. While you lavish affection on one, putting the rest

in the sack."

"It was the most merciful thing to do," Prim retorted. "There was no

pain—only instantaneous obliteration."

Oktav reacted. All his earlier doubts and flashes of rebellion were

suddenly consolidated into a burning desire to shake the complacency of

the others. He gave his ironic thoughts their head, sent them whipping

through the dark.

"Who are you to tell whether or not there's pain in instantaneous

obliteration? Oh yes, the botched worlds, the controls, the experiments

that failed—they don't matter, let's put them out of their misery,

let's get rid of the evidence of our mistakes, let's obliterate them

because we can't stand their mute accusations. As if the Earthlings

of the botched worlds didn't have as much right to their future, no

matter how sorry and troubled, as the Earthlings of the main trunk.

What crime have they committed save that of guessing wrong, when,

by your admission, all was guess-work? What difference is there

between the main trunk and the lopped branches, except your judgment

that the former seems happier, more successful? Let me tell you

something. You've coddled the main-trunk world for so long, you've

tied your limited human affections to it so tightly, that you've

gotten to believing that it's the only real world, the only world that

counts—that the others are merely ghosts, object lessons, hypothetics.

But in actuality they're just as throbbingly alive, just as deserving

of consideration, just as real."

"They no longer exist," thought Prim crushingly. "It is obvious that

your mind, tainted by Earth-bound emotions, has become hopelessly

disordered. You are pleading the cause of that which no longer is."

"Are you so sure?" Oktav could feel his questioning thought hang in

the dark, like a great black bubble, coercing attention. "What if the

botched worlds still live? What if, in thinking to obliterate them,

you have merely put them beyond the reach of your observation, cut

them loose from the main-trunk time-stream, set them adrift in the

oceans of eternity? I've told you that you ought to visit the world

more often in the flesh. You'd find out that your beloved main-trunkers

are becoming conscious of a shadowy, overhanging danger, that they're

uncovering evidences of an infiltration, a silent and mystery-shrouded

invasion across mental boundaries. Here and there in your main-trunk

world, minds are being displaced by minds from somewhere else. What if

that invasion comes from one of the botched worlds—say from one of the

worlds of the last trifurcation? That split occurred so recently that

the alternate worlds would still contain many duplicate individuals,

and between duplicate individuals there may be subtle bonds that

reach even across the intertime void—on your admission, time-splits

are never at first complete, and there may be unchanging shared

deeps in the subconscious minds of duplicate individuals, opening the

way for forced interchanges of consciousness. What if the botched

worlds have continued to develop in the everlasting dark, outside

the range of your knowledge, spawning who knows what abnormalities

and horrors, like mutant monsters confined in caves? What if, with

a tortured genius resulting from their misery, they've discovered

things about time that even you do not know? What if they're out

there—waiting, watching, devoured by resentment, preparing to leap

upon your pet?"

Oktav paused and probed the darkness. Faint, but unmistakable, came the

pulse of fear. He had shaken their complacency all right—but not to

his advantage.

"You're thinking nonsense," Prim thundered at him coldly, in

thought-tones in which there was no longer any hope of mercy or

reprieve. "It is laughable even to consider that we could be guilty

of such a glaring error as you suggest. We know every crevice of

space-time, every twig and leaflet. We are the masters of the

Probability Engine."

"Are you?" Reckless now of all consequences, Oktav asked the

unprecedented, forbidden, ultimate question. "I know when I was

initiated, and presumably when the rest of you were initiated, it

was always assumed and strongly suggested, though never stated with

absolute definiteness, that Prim, the first of us, a mental mutant and

supergenius of the nineteenth century, invented the Probability Engine.

I, an awestruck neophyte, accepted this attitude. But now I know that

I never really believed it. No human mind could ever have conceived

the Probability Engine. Prim did not invent it. He merely found it,

probably by chancing on a lost talisman. Thereafter some peculiarity of

the Engine permitted him to take it out of reach of its true owners,

hide it from them. Then he took us in with him, one by one, because a

single mind was insufficient to operate the Engine in all its phases

and potentialities. But Prim never invented it. He stole it."

With a sense of exultation, Oktav realized that he had touched their

primal vulnerability—though at the same time insuring his own doom.

He felt the seven resentful, frightened minds converge upon him

suffocatingly. He probed now for one thing only—any relaxing of

watchfulness, any faltering of awareness, on the part of any one of

them. And as he probed, he kept choking out additional insults against

the resistance.

"Is there any one of you, Prim included, who even understands the

Probability Engine, let alone having the capacity to devise it?

"You prate of science, but do you understand even the science of modern

Earthlings? Can any one of you outline to me the theoretic background

of subtronic physics? Even your puppets have outstripped you. You're

atavisms, relics of the Dawn Civilization, mental mummies, apes crept

into a factory at night and monkeying with the machinery.

"You're sorcerer's apprentices—and what will happen when the sorcerer

comes back? What if I should stop this eternal whispering and send a

call winging clear and unhampered through eternity: 'Oh sorcerer, True

Owners, here is your stolen Engine'?"

They pressed on him frantically, frightenedly, as if by sheer mental

weight to prevent any such call being sent. He felt that he would go

down under the pressure, cease to be. But at the same time his probing

uncovered a certain muddiness in Kart's thinking, a certain wandering

due to doubt and fear, and he clutched at it, desperately but subtly.

Prim finished reading sentence. "—and so Ters and Septem will

escort Oktav back to the world, and when he is in the flesh, make

disposition of him." He paused, continued. "Meanwhile, Sikst will make

an expedition to recover the lost talisman, calling for aid if not

immediately successful. At the same time, since the functioning of the

Probability Engine is seriously hampered so long as there is an empty

station, Sekond, Kart and Kant will visit the world in order to select

a suitable successor for Oktav. I will remain here and—"

He was interrupted by a flurry of startled thought from Kart, which

rose swiftly to a peak of dismay.

"My talisman! Oktav has stolen it! He is gone!"

VI.

By her battened hatch I leaned and caught

Sounds from the noisome hold—

Cursing and sighing of souls distraught

And cries too sad to be told.

Gloucester Moors, William Vaughn Moody.

Thorn teetered on the dark edge. His footgear made sudden grating

noises against it as he fought for balance. He was vaguely conscious of

shouts and of a needle of green light swinging down at him.

Unavailingly he wrenched the muscles of his calves, flailed the air

with his arms.

Yet as he lurched over, as the edge receded upward—so slowly at

first!—he became glad that he had fallen, for the down-chopping green

needle made a red-hot splash of the place where he had been standing.

He plummeted, frantically squeezing the controls of flying togs he was

not wearing.

There was time for a futile, spasmodic effort to get clear in his mind

how, plunging through the forest, he should find himself on that dark

edge.

Indistinct funnel-mouths shot past, so close he almost brushed them.

Then he was into something tangly that impeded his fall—slowly at

first, then swiftly, as pressures ahead were built up. His motion was

sickeningly reversed. He was flung upward and to one side, and came

down with a bone-shaking jolt.

He was knee-deep in the stuff that had broken his fall. It made a

rustling, faintly skirring noise as he ploughed his way out of it.

He stumbled around what must have been a corner of the dark building

from whose roof he had fallen. The shouts from above were shut off.

He dazedly headed for one of the bluish glows. It faintly outlined

scrawny trees and rubbish-littered ground between him and it.

He was conscious of something strange about his body. Through the

twinges and numbness caused by his fall, it obtruded itself—a feeling

of pervasive ill-health and at the same time a sense of light, lean

toughness of muscular fiber—both disturbingly unfamiliar.

He picked his way through the last of the rubbish and came out at the

top of a terrace. The bluish glow was very strong now. It came from the

nearest of a line of illuminators set on poles along a broad avenue

at the foot of the terrace. A crowd of people were moving along the

avenue, but a straggly hedge obscured his view.

He started down, then hesitated. The tangly stuff was still clinging

to him. He automatically started to brush it off, and noted that it

consisted of thin, springy spirals of plastic and metal—identical with

the shavings from an old-style, presubtronic hyperlathe. Presumably

a huge heap of the stuff had been vented from the funnel-mouths he

had passed in his fall. Though it bewildered him to think how many

hyperlathes must be in the dark building he was skirting, to produce

so much scrap. Hyperlathes were obsolete, almost a curiosity. And to

gather so many engines of any sort into one building was unthought of.

His mind was jarred off this problem by sight of his hands and

clothing. They seemed strange—the former pallid, thin, heavy-jointed,

almost clawlike.

Sharp but far away, as if viewed through a reducing glass, came

memories of the evening's events. Clawly, the symchromy, the old man in

black, the conference in the Sky Room, his plunge through the forest.

There was something clenched in his left hand—so tightly that the

fingers opened with difficulty. It was the small gray sphere he had

stolen at the Yggdrasil. He looked at it disturbedly. Surely, if he

still had that thing with him, it meant that he couldn't have changed.

And yet—

His mind filled with a formless but mounting foreboding.

Under the compulsion of that foreboding, he thrust the sphere into

his pocket—a pocket that wasn't quite where it should be and that

contained a metallic cylinder of unfamiliar feel. Then he ran down

the terrace, pushed through the straggly hedge, and joined the crowd

surging along the blue-litten avenue.

The foreboding became a tightening ball of fear, exploded into

realization.

That other Thorn had changed places with him. He was wearing that other

Thorn's clothing—drab, servile, workaday. He was inhabiting that other

Thorn's body—his own but strangely altered and ill-cared-for, aquiver

with unfamiliar tensions and emotions.

He was in the world of his nightmares.

He stood stock-still, staring, the crowd flowing around him, jostling

him wearily.

His first reaction, after a giant buffet of amazement and awe that left

him intoxicatedly weak, was one of deep-seated moral satisfaction. The

balance had at last been righted. Now that other Thorn could enjoy

the good fortunes of utopia, while he endured that other Thorn's lot.

There was no longer the stifling sense of being dominated by another

personality, to whom misfortune and suffering had given the whiphand.

He was filled with an almost demoniac exhilaration—a desire to explore

and familiarize himself with this world which he had long studied

through the slits of nightmare, to drag from the drifting crowd around

him an explanation as to its whys and wherefores.

But that would not be so easy.

An atmosphere of weary secrecy and suspicion pervaded the avenue. The

voices of the people who jostled him dropped to mumbles as they went

by. Heads were bowed or averted—but eyes glanced sharply.

He let himself move forward with the crowd, meanwhile studying it

closely.