In a strange house anything might happen.

The CAT in GRANDFATHER'S HOUSE

by

CARL GRABO

illustrated by

M. F. ISERMAN

CHICAGO NEW YORK

NEW YORK

LAIDLAW BROTHERS

Copyright, 1929

By LAIDLAW BROTHERS

Incorporated

All rights reserved

Printed in U.S.A.

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

It is peculiarly fitting in this day of delightful juveniles that an author of many books on the technique of writing should turn his pen to the writing of this child's book.

Carl Grabo, with whose name "The Art of the Short Story" is at once associated, has written this whimsical and imaginative tale of Hortense and the Cat. Antique furniture, literally stuffed with personality, hurries about in the dim moonlight in order to help Hortense through a thrillingly strange campaign against a sinister Cat and a villainous Grater. The book offers rare humor, irresistible alike to grown-ups and children.

It is a book that will stimulate the imagination of the most prosaic child—or at least give it exercise! Wonder, the most fertile awakener of intelligence, and vision are closely akin to imagination, and both are greatly needed in this work-a-day world.

Each reader, a child at heart be he seven or seventy, will bubble with the glee of childhood at all its quaint imaginings. They are so real that they seem to be true.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | "... going to the big house to live" | 9 |

| II. | "And the darker the room grew, the more it seemed alive" | 20 |

| III. | "They could hear the soft pat-pat of padded feet in the hall" | 31 |

| IV. | "Highboy, and Lowboy, and Owl, and the Firedogs come out at night" | 48 |

| V. | "Jeremiah's disappeared again" | 60 |

| VI. |

"I'll have the charm That saves from harm" |

74 |

| VII. | "... there should be Little People up the mountain yonder" | 93 |

| VIII. | "The sky was lemon colored, and the trees were dark red" | 109 |

| IX. | "Tell us a story about a hoodoo, Uncle Jonah" | 128 |

| X. |

"Ride, ride, ride For the world is fair and wide" |

134 |

| XI. | "... take us to the rock on the mountain side where the Little People dance" | 145 |

| XII. | "There are queer doings in this house" | 169 |

| XIII. | "This is what was inside" | 186 |

Chapter I

"... going to the big house to live."

Hortense's father put the letter back into its envelope and handed it across the table to her mother.

"I hadn't expected anything of the kind," he said, "but it makes the plan possible provided——"

Hortense knew very well what Papa and Mamma were talking about, for she was ten years old and as smart as most girls and boys of that age. But she went on eating her breakfast and pretending not to hear. Papa and Mamma were going a long way off to Australia, provided Grandmother and Grandfather would care for Hortense in their absence. So Mamma had written, and this was the answer.

"Would you like to stay with Grandfather and Grandmother while Papa and Mamma are away?" her mother asked.

Hortense would like it very much, for she had never been in her grandfather's house. Grandfather and Grandmother had always visited her at Christmas and other times, and she had imagined wonderful stories of the house that she had never seen. All her father would tell of it when she asked him was that it was large and old-fashioned. Once only she had heard him say to her mother, "It would be a strange house for a child."

Strange houses were her delight. In a strange house anything might happen. Always in fairy tales and wonder stories, the houses were deliriously strange.

So when her mother asked her the question, Hortense answered promptly, "Yes, ma'm."

"I'm afraid you'll have no one to play with," Mamma said, "but there will be nice books to read and a large yard to enjoy. Besides, the house itself is very unusual. If you were an imaginative child it might be a little—but then you aren't imaginative."

"Yes, ma'm," said Hortense.

She supposed Mamma was right. If she were really imaginative, no doubt she would have seen a fairy long ago. But though she looked in every likely spot, never had she seen any except once, and that time she wasn't sure.

"My little girl is sensible and not likely to be easily frightened at any unusual or strange—," her father began.

"I shouldn't, Henry," Mamma interrupted swiftly.

"No, perhaps not," Papa agreed.

No more was said, but Hortense knew very well that going to Grandfather's house would be a grand and delightful adventure and that almost anything might happen, provided she were imaginative enough. She reread all her fairy tales by way of preparation, and her dreams grew so exciting that at times she was sorry to wake up in the morning.

Meanwhile, Papa and Mamma were busy packing and putting things away in closets. Finally the day came when Hortense kissed her mamma good-by and cried a little, and Papa took her to the station and, after talking to the conductor, put her on the train.

The conductor said he would take good care that Hortense got off at the right station; then Papa found a seat for her by a window, put her trunk check in her purse and her box of lunch and her handbag beside her, kissed her good-by, and told her to be a brave girl.

He stood outside her window until the train started; then he waved his hand, and Hortense saw him no more. However, she felt sad only for a minute or two, for he was going to Australia and was going to bring her something very interesting, possibly a kangaroo. She had asked for a kangaroo, and Papa had shaken his head doubtfully and said he'd see. But Papa always did that to make the surprise greater.

It was an interesting trip, and Hortense wasn't tired a bit. The conductor came in several times and asked her many questions about her grandfather and her grandmother. He also told her about his own little girl who was just Hortense's age and a wonder at fractions.

When it was time for lunch, the porter brought her a little table upon which she spread the contents of her box, and she had a pleasant luncheon party with an imaginary little boy named Henry. It was all the nicer because she had to eat all Henry's sandwiches and cookies, whereas, if Henry had been a real little boy, he would have eaten them all himself and probably some of hers, too.

After luncheon, the train went more slowly as it climbed into the mountains, and all the rest of the way Hortense looked out of the window. She had never seen big mountains before. Then, about four o'clock in the afternoon, the conductor came and told her to get ready. When the train stopped, he helped her off, called, "All aboard" (though there was nobody to get on), and the train drew away and disappeared.

Hortense was all alone, and there was nobody resembling her grandfather, or her grandfather's old coachman, to meet her. She felt very lonesome until a man with a bright metal plate on his cap, which read Station Agent, came to her and asked her name and where she belonged.

"So you're Mr. Douglas' granddaughter," said he, "and are going to the big house to live. Well, well! I guess Uncle Jonah will be along pretty soon."

Hortense went with him and looked up the long street of the little town. The station agent shaded his eyes with his hand.

"I guess that's Uncle Jonah now," said he, and Hortense saw an old-fashioned surrey with a fringed top drawn by two very fat black horses. They were very lazy horses, and it seemed a long time before they drew up at the station and Uncle Jonah climbed painfully out.

Uncle Jonah was very old and black, and his hair was white and kinky.

"Yo's Miss Hortense, isn't yo'?" he asked. "I come fo' to git yo'. I'se kinda' late 'cause Tom an' Jerry, dey jes' sa'ntered along."

The station agent and Uncle Jonah lifted Hortense's steamer trunk into the back seat of the surrey, and with Hortense sitting beside Uncle Jonah, off they went.

"She'd better look out for ghosts up at the big house, hadn't she, Uncle Jonah?" the station agent called after them.

Uncle Jonah grunted.

"Are there ghosts at Grandfather's house?" Hortense asked, feeling a delightful shiver up her back.

"'Cose not," said Uncle Jonah uneasily. "Dat's jes' his foolishness."

"I'd like to see a ghost," said Hortense.

Uncle Jonah stared at her.

"Me, I don' mix up wid no ha'nts," said he. "When I hears 'em rampagin' 'roun' at night, I pulls de kivers up an' shuts mah eyes tight."

"What do they sound like, Uncle Jonah?" Hortense asked breathlessly.

But Uncle Jonah would not answer. Instead he clucked to the horses, and not another word could Hortense get from him for a long time. They drove through the little town and out into the country toward the mountains.

"Is the house right among the mountains?" Hortense asked at last.

"It sho' is," said Uncle Jonah, "De's a mount'in slap in de back yard."

"Goody," said Hortense. "I like mountains."

"Dey's powahful oncomfo'table," grumbled Uncle Jonah.

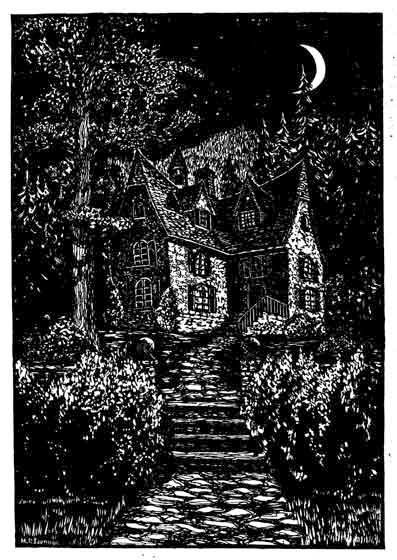

He stopped the horses on the top of a little hill and pointed with his whip.

"De's de house," he said, "dat big one wid de cupalo."

Hortense looked as directed. Below them, at the foot of a steep mountain, was a tall house with a cupola. It was three stories high, old-fashioned, and had high shuttered windows. The cupola attracted Hortense particularly. She thought she would like to sit high inside and look through the little windows. One could see ever so far and could pretend one were in a lighthouse or on the mast on a ship.

Tom and Jerry walked slowly down the long hill. At its foot was a little house surrounded by a low hedge. A boy of about Hortense's age was playing in the yard. He stopped and stared at Hortense as she passed, and Hortense stared back. Then the boy did a handspring and waved his hand.

"What's that boy's name?" Hortense asked.

Uncle Jonah raised his eyes.

"Good fo' nothin'," muttered Uncle Jonah. "Ef I catches him in my o'cha'd ag'in, I'll lambaste him good."

"He looks like a nice boy," said Hortense.

"Dey ain't no nice boys," said Uncle Jonah. "Dey all needs a lickin'."

Tom and Jerry turned in at a graveled driveway and trotted through a large lawn set with big trees and clumps of shrubbery. They stopped before the big house, and Uncle Jonah and Hortense got down. The wide door opened, and there stood Grandmother in her white lace cap and black silk dress, as always.

Hortense ran up the steps and kissed her. Grandmother was little, with white hair and bright eyes. They entered the old-fashioned hallway together, and Hortense knew at once that the house would be all that she had hoped.

The hall was dark, and old-fashioned furniture sat along the walls. A spidery staircase with dark wood bannisters rose steeply from one side and wound away out of sight. At the far end of the hall was a great friendly grandfather's clock with a broad round face.

"Tick-tock, tick-tock," said the clock in a deep mellow voice. Hortense thought he said, "Welcome, welcome," and was sure he winked at her.

"I must make him talk to me," thought Hortense. "He seems a very wise old clock. How many interesting things he must know."

A middle-aged woman with a kind face came to meet them.

"Mary, this is my little granddaughter," said Grandmother; and to Hortense, "Mary will take care of you and show you your room. When you have taken your things off, come downstairs and we will have tea."

Hortense followed Mary up the steep, winding stairs to the second floor. Mary opened one of the many doors of the long hallway, and Hortense followed her into a large old-fashioned room with a great four-poster bed. It was a corner room. Through the windows on one side Hortense could look out over the orchard slope that ran down to the brook. Beyond the brook rose a shadowy mountain whose side was so steep that trees could hardly find a foothold among the rocks. On the other side of the room, the windows opened upon the lawn bordered by a hedge. Beyond the hedge was the little house in front of which Hortense had seen the boy, but he was no longer playing in the yard.

A big man carried up Hortense's trunk and placed it in the corner. He had bright blue eyes. Mary introduced him to Hortense.

"This is my husband, Fergus," said she. "We live in the little house beyond the orchard. You must come to see us sometime and have tea. My husband will tell you stories of the Little People."

"The Little People are fairies, aren't they, who live in Ireland?" said Hortense, remembering her fairy tales.

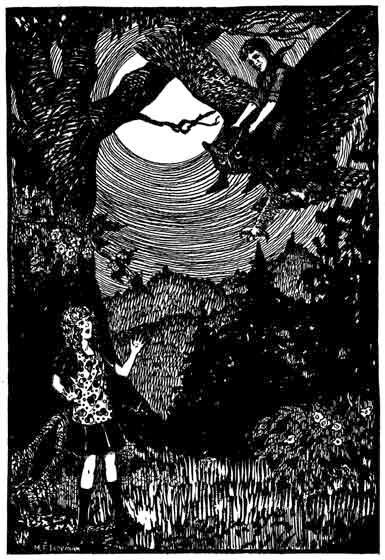

"Not only in Ireland," said Fergus, "but everywhere in woods and mountains. Do you see that dark place in the rocks halfway up the mountain?"

Hortense looked as directed and thought she saw the place.

"That's the mouth of a cave that goes into the mountain, nobody knows how far," said Fergus. "It is certain that the Little People must live in there."

His eyes twinkled, but his face was quite serious.

"Really?" Hortense asked.

"I've not seen them," said Fergus, "but my eyes are older than yours. I do not doubt that you will see them dancing on moonlight nights."

Meanwhile, Mary had been unpacking the trunk and laying Hortense's things away in the drawers of a great bureau.

"Now we will go down and have tea," said Mary. "Let me brush your hair a bit."

After this was done, they went downstairs again, passed the big clock that winked and said, "Tick-tock, hello," and entered a sunny room where Grandmother sat in her easy chair.

Chapter II

"And the darker the room grew, the more it seemed alive."

In Grandmother's room there were tall south windows reaching nearly to the ceiling. It must have been bright with sunshine in midday, but it was nearly evening now and the lower halves of the windows were closed with white shutters, which gave the room a very cosy appearance. In the white marble fireplace a cheerful fire was burning, and above it on the mantel was a large stuffed owl as white as the marble on which he was perched. He seemed quite alive and very wise, his great yellow eyes shining in the firelight. Hortense glanced at him now and then, and always his bright eyes seemed fixed upon her.

"I believe he could talk if he would," thought Hortense. "Sometime when we're alone, I'll ask him if he can't."

"Now, if you'll call your grandfather, we'll have tea," said Grandmother. "He's in his library in the next room."

Hortense ran to do as she was told. The library was walled with books, thousands of them, and near a window Grandfather sat at a big desk, busily writing. He looked up when Hortense entered, and laid down his pen to take her on his knee.

Grandfather had white hair, and bushy white eyebrows over piercing dark eyes. Hortense had always thought him very handsome, particularly when he walked, for he was tall and very straight. She thought he must look like a Sultan or Indian Rajah, such as is told of in the Arabian Nights, for his skin was dark, and when he told her stories of his youth and his wanderings about the earth, she wondered if he weren't really some foreign prince merely pretending to be her grandfather. He had been in many strange places in India, Africa, and the South Seas, and when he chose, he could tell wonderful stories of his adventures.

While Grandfather held her on his lap, Hortense gazed at a strange bronze figure which stood on a stone pedestal beside his desk. It was a bronze image such as Hortense had seen pictured in books—some sort of an idol, she thought. The figure sat cross-legged like a tailor and in one hand held what seemed to be a bronze water lily. Hortense had never seen an image or statue that seemed so calm, as though thinking deep thoughts which it would never trouble to express.

"What a funny little man," said Hortense.

Grandfather looked gravely at the bronze figure.

"That is an image of Buddha, the Indian god," he said. "Perhaps after dinner I'll tell you a story about him."

He lifted Hortense from his knee and, taking her by the hand, went into Grandmother's room.

Mary had brought in the tea wagon, which Hortense thought looked like a dwarf. Indeed, all the furniture seemed curiously alive, as though it could talk if it would. In the corner was a lowboy. With the firelight falling on its polished surface and on the bright brass handles to its drawers, it seemed to make a fat smiling face, as of a good-humored boy.

"What a jolly face," Hortense thought. "He'd be good fun to play with, I'm sure."

She ate her toast and cake while Grandfather and Grandmother talked together in the twilight. And the darker the room grew, the more it seemed alive.

"I believe all these things are talking," said Hortense to herself. "Now, if I could only hear! Perhaps if I had an ear trumpet or something——"

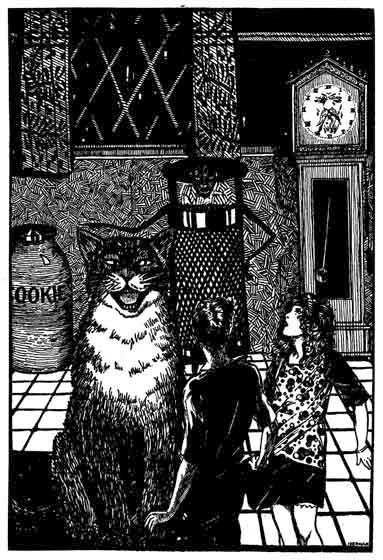

As she was thinking thus, a great tortoise-shell cat walked calmly in, seated himself on the hearth-rug, and stared into the fire. It seemed to Hortense that the flredogs fairly leaped out at him, but the cat only gazed placidly at them.

"He knows they can't get at him," thought Hortense, "and he's saying something to make them mad."

Grandfather and Grandmother were talking in a low tone, and Hortense suddenly found herself listening to them with interest.

"Uncle Jonah says it's a 'ha'nt,'" Grandfather was saying with a smile. "He and Esmerelda are afraid and want me to fix up the rooms over the stable."

"What nonsense!" Grandmother exclaimed sharply.

"But there is something odd about the house, you know," said Grandfather.

"I believe that you think it's a ghost yourself, Keith," said Grandmother, looking keenly at him.

"I've always wanted to see a ghost," admitted Grandfather, "but I've had no luck. Why shouldn't there be ghosts? All simple peoples believe in them."

"Remember Hortense," Grandmother said in a low voice.

"To be sure," Grandfather answered, looking quickly at Hortense.

Hortense heard with all her ears, but her eyes were upon the cat. The cat sat with a smile on his face and one ear cocked. Once he looked at Grandfather and laughed, noiselessly.

"The cat understands every word!" Hortense said to herself with conviction. She began to be a little afraid of the cat, for she felt that everything in the room disliked him. The lowboy no longer smiled but looked rather solemn and foolish. The chairs stood stiffly, as though offended at his presence. The white owl glared fiercely with his yellow eyes, and the firedogs fairly snapped their teeth.

But the cat did not mind. He lay on the hearthrug and grinned at them all. Then he rolled over on his back, waved his paws in the air, and whipped his long tail.

"He's laughing at them!" said Hortense to herself. "And he knows all about the 'ha'nt,' whatever that is!"

Mary came to remove the tea wagon, which Hortense decided was really good at heart but surly and tart of temper because of his deformity. The brass teakettle looked to be good-tempered but unreliable.

"There's something catlike about a teakettle," Hortense reflected. "It likes to sit in a warm place and purr. And it likes any one who will give it what it wants. Its love is cupboard love."

"Dinner isn't until seven," said Grandmother, "so perhaps you'd like to go to the kitchen and see Esmerelda, the cook, Uncle Jonah's wife. If you are nice to her, it will mean cookies and all sorts of good things."

Hortense thought, "If I'm nice to Esmerelda just to get cookies, I'll be no better than the cat and the teakettle; so I hope I can like her for herself." Nevertheless, it would be nice to have cookies, too.

"Isn't this an awfully big house?" said Hortense to Mary as they went down a long dark passage.

"Much too big," said Mary. "I spend my days cleaning rooms that are never used. There's the whole third floor of bedrooms, not one of which has been slept in for years. Then there are the parlors, and many closets full of things that have to be aired, and sunned, and kept from moths."

"May I go with you, Mary, when you clean?" Hortense asked. "I'll help if I can."

"Sure you may," said Mary kindly. "I'll be glad to have you. You'll be company. Some of those dark closets, and the bedrooms with sheeted chairs and things give me the creeps. An old house and old unused rooms are eerie-like. Sometimes I can almost hear whispers, and sighs, and things talking."

"I know," said Hortense. "Everything talks—chairs, and tables, and bureaus, and everything. Only I can never hear just what it is they say. Do you think they move sometimes at night?"

"I'll never look to see," said Mary piously. "At night I stay in my own little house, where everything is quiet and homelike and there are no queer things about."

Hortense shivered delightfully. Perhaps she would see and hear the queer things, and even see the "ha'nt" of which Grandfather had spoken.

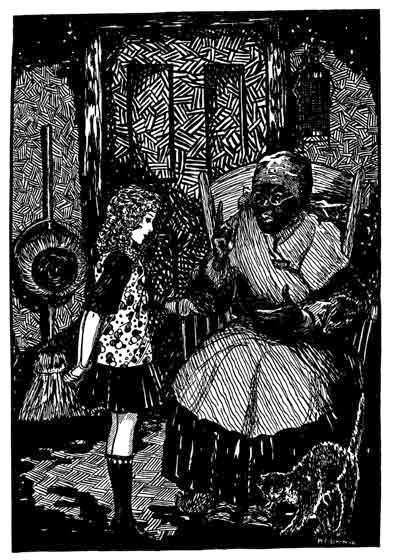

The kitchen was a large comfortable place. A bright fire was burning in the range. Shining pans hung on the wall, and Aunt Esmerelda, large, fat, and friendly, with a white handkerchief tied over her head, moved slowly among them.

Aunt Esmerelda put her hands on her hips and looked down at Hortense.

"Yo's the spittin' image of yo' ma, honey," said Aunt Esmerelda. "Does yo' like ginger cookies?"

"Yo's the spittin' image of yo' ma, honey," said Aunt Esmerelda.

Hortense doted on ginger cookies.

"De's de jar," said Aunt Esmerelda, pointing to a big crock on the pantry shelf. "Whenevah yo's hongry, jes' yo' he'p yo'se'f."

Hortense sat on a chair in the corner, out of the way, and watched Aunt Esmerelda cook.

"What was the thing you and Uncle Jonah heard?" she asked at last abruptly.

"Wha's dat?" Aunt Esmerelda said, dropping a saucepan with a clatter. "Who tole you 'bout dat?"

"I heard Grandpa talking to Grandma about it," said Hortense.

"It wan't nothin'?" said Esmerelda uneasily. "Don' yo' go 'citin' yo'se'f 'bout dat. Jes' foolishness."

"But if there is a 'ha'nt' in the house, I want to see it," Hortense persisted.

Aunt Esmerelda stared at her with big eyes.

"Who all said anythin' 'bout dis yere ha'nt? I ain't never heard of no ha'nt."

"When you hear it again, please wake me up if I'm asleep," said Hortense.

"Heavens, I don' get outa' mah bed w'en I hears nothin'," said Aunt Esmerelda. "Not by no means. E'n if yo' hears anythin', jes' yo' shut yo' eahs and pull the kivers ovah yo' head. Den dey don' git yo'."

But Hortense felt quite brave by the bright kitchen fire. She sat very quietly and watched Aunt Esmerelda at work. The kitchen was filled with bright friendly things—shining pans and spoons, a squat, fat milk jug with a smiling face, a rolling pin that looked very stupid, an egg beater that surely must get as dizzy as a whirling dervish turning round and round very fast—probably quite a scatterbrain, Hortense thought.

"What is that, Aunt Esmerelda?" Hortense asked, pointing to a bright rounded utensil hanging above the kitchen table.

Aunt Esmerelda looked.

"Dat's a grater, chile. I grates cheese an' potatoes an' cabbage an' things wid dat."

She took down the grater.

"On dis side it grates things small and on dis side big."

She hung it in its place again.

"It looks wicked to me," said Hortense. "I shouldn't like to meet it wandering around the house at night."

"Laws, chile, how yo' talks," Aunt Esmerelda exclaimed startled. "Yo' gives me de fidgets. Wheh yo' git ideas like dat?"

"Things look that way," said Hortense. "Some look friendly and some unfriendly. There's the cat and the teakettle. They aren't friendly. They say all sorts of sly things. Sometime I'm going to hear what they are. The grater would run after you and scrape you on his sharp sides if he could."

Aunt Esmerelda shook her head uneasily. From time to time she stared at Hortense.

"Yo's a curyus chile," she muttered. "I don' know what yo' ma means a-bringin' yo' up disaway, scaihin' po' ole Aunt Esmerelda. Lan's sakes, if I ain't done forgit de pertatahs! An' dey's all in de stoh'room!"

"Where's that?" Hortense asked much interested.

"In de basement," said Aunt Esmerelda, "an' it's powahful dark down deh."

"I'll go with you," said Hortense eagerly. "I'd like to see it."

Aunt Esmerelda lighted a candle and, taking a large pan, opened the door leading to the basement.

It was a large basement, and the candle was not sufficient to light its more remote corners. They passed a huge dark furnace with its arms stretching out on all sides like a spider's legs. In front of it was a coal bin, large and black.

Aunt Esmerelda opened the door of the storeroom. Within were barrels and boxes, and hanging shelves laden with row upon row of preserves in jars and regiments of jelly glasses, each with its paper top and its white label.

Aunt Esmerelda filled her pan with potatoes from the barrel and led the way from the storeroom. Closing the door, she led the way back upstairs.

A sudden noise of something falling and of little scurrying feet led her to stop abruptly. Hortense drew close to her. Aunt Esmerelda was shaking, and by the light of the candle Hortense could see the whites of her eyes gleaming as she looked all about her.

They started again for the cellar stairs. When they had reached the furnace, a sudden gust of wind blew out the candle. In a far corner of the cellar something rattled.

Aunt Esmerelda started to run, and Hortense ran after her. A faint light from the kitchen shone on the head of the cellar stairs. Aunt Esmerelda hurried up the stairs, panting, with Hortense at her heels. At the top Aunt Esmerelda slammed and bolted the door; then she sank into a chair and mopped her perspiring face.

"Do you think it was the 'ha'nt'?" Hortense asked much excited.

"Don' speak to me 'bout no ha'nt!" exclaimed Aunt Esmerelda angrily. "Yo' sho' scaihs me. Run along and git ready fo' dinnah."

Though Hortense lingered, Aunt Esmerelda would not say another word, and finally Hortense went to change her dress.

Chapter III

"They could hear the soft pat-pat of padded feet in the hall."

Dinner was served in the large dining room. Friendly clusters of candles stood on the round mahogany table and made little pools of light on its bright surface. Mary waited on them.

"I wonder what's the matter with Aunt Esmerelda to-night," said Grandpa after the soup. "These potatoes aren't done, and the roast is burned."

"I think she was frightened at something in the cellar," said Hortense.

"What's that?" Grandpa questioned, and Hortense told him of the noise and the candle going out.

"A rat probably," said Grandpa. "Weren't you frightened?"

"A little," Hortense replied truthfully, "but I think it was because Aunt Esmerelda was so afraid."

Grandpa looked at her, smiling under his bushy eyebrows.

"Would you go down to the storeroom and get me an apple if I gave you something nice for your own?" he asked.

"Don't, Keith," said Grandma sharply. "You'll frighten the child."

"I don't want her to be afraid in the dark," said Grandpa. "This is a big house and much of it is dark."

Hortense was silent, thinking.

"I'll go," she said.

"Good," said Grandpa. "Bring me a plateful of northern spies."

Hortense arose from the table and walked to the door. As she went out, she heard Grandmother say, "You'll frighten the child——" The rest she didn't hear.

In the kitchen Hortense found Aunt Esmerelda seated in her chair, gazing gloomily at the kitchen range.

"May I have a candle, Aunt Esmerelda?" Hortense asked.

"What fo' yo' wants a candle?" Aunt Esmerelda demanded.

"I'm going to the storeroom to get Grandpa some apples," said Hortense.

Aunt Esmerelda stared at her without speaking for some moments.

"All by yo'se'f'?" she demanded at last.

"All by myself," said Hortense.

Aunt Esmerelda shook her head and muttered, but rising, found a candle and lighted it.

"Ef yo' say yo' prayahs, mebbe nothin'll git yo'," she said ominously.

It was black as a hat in the basement, and little shivers ran up and down Hortense's spine, but she ran quickly to the storeroom and filled her plate with apples from the big barrel.

Starting back she heard a noise and stopped, her heart pounding and little pin pricks crinkling her scalp; then she hurried to the stairs, almost running. But she did not run up the stairs, for she didn't wish to have Aunt Esmerelda think her afraid.

She was a glad little girl, nevertheless, when she was safe again in the light kitchen.

"Yo' didn' see nothin'?" demanded Aunt Esmerelda.

"I didn't see anything," said Hortense. "I heard something, but it was probably only a rat." She spoke bravely, quite like Grandfather.

"'Twan't no rat," muttered Aunt Esmerelda gloomily, shaking her head. "It's a ha'nt or a ghos'. Dey's ha'nts and ghos's all 'roun dis place."

Hortense began to feel quite brave after she had arrived safely in the cheerful dining room. Grandfather looked at her, shrewdly smiling.

"Did you see or hear anything?" he asked.

"I heard—a noise," replied Hortense.

"And were you afraid?" he asked again.

Hortense looked into his bright, kind eyes.

"A little," she confessed.

Grandfather took her on his knee.

"It isn't being afraid that matters," he said. "It's doing what you set out to do whether afraid or not That's what it is to be brave."

"Really?" Hortense asked.

"Yes, really," assured Grandfather. "It is not brave to be without fear, but to overcome it. Now we'll go into the library, and I'll tell you the promised story and give you something—but what it is, I'll not reveal until later."

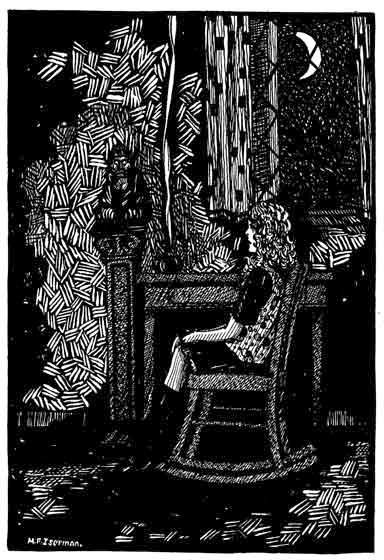

Grandmother returned to her chair and her knitting, with the white owl and the cat for company, and Grandfather and Hortense found a comfortable seat in Grandfather's big chair. There was a cheerful fire on the hearth, and Grandfather's study lamp cast a bright light upon his desk—but the bronze Buddha remained in a shadow, and the rows of books along the walls were scarcely visible.

"When I was a young lad in Scotland," said Grandfather when Hortense was seated on his knee with her head upon his shoulder, "I had a close friend of my own age whose name was Dugald—Dugald Stewart. We grew up together, and when we became young men, we set off together to see the world and to make our fortunes.

"We visited many strange and wonderful places and had many adventures, some of which I shall tell you about, perhaps. Our fortunes were up and down, usually down. We sought for pearls in the Indian Ocean and the South Seas, and for gold in Australia. We traded with the natives here, there, and everywhere, but our fortunes were still to be made, and it seemed we might spend our lives without being much better off than we were then.

"At last Dugald and I parted company. I was to go on a trading journey into the interior of Borneo, which, as you know, is a very large island in the East Indies. Dugald set out upon a wild expedition into Burma. We had heard a story of a rare and valuable jewel said to be in a remote and little-known part of the interior. I had tried to dissuade him from so dangerous and uncertain an attempt, but he was brave and even reckless. Besides, my own adventure was dangerous also.

"Before we parted, Dugald gave me a little charm which he always wore and in which he had great faith. It was supposed to bring luck and to shield from danger. Perhaps it did, for I was very lucky thereafter and had many wonderful escapes from death. It was not so with Dugald. I never saw him again, and I wish now that he had kept the charm. Perhaps it would have protected him."

Grandfather paused and glanced at the bronze figure of Buddha beyond the circle of the lamplight.

"This image was his last gift to me, brought by his trusted servant with the message that in it lay fortune and that I should always keep it by me—and I have always done so."

"Did he find the valuable jewel?" Hortense asked breathlessly.

"That I never knew," said Grandfather. "The servant told me a wild story of his master's finding it, but when my friend died suddenly, the servant could find no trace of it. I think he was honest, too.

"But the jewel isn't the point of my story—rather, the charm."

Grandfather opened a drawer of his desk and drew forth a tiny box of sweet smelling wood—sandalwood, Grandfather called it. He bade Hortense lift the cover. Inside the box lay a tiny ivory monkey attached to a tarnished silver chain.

"It can be worn around the neck," said Grandfather, drawing it forth. Placing the chain about Hortense's neck, he fastened the ends in a secure little clasp.

"Now you'll have good luck and nothing can harm you," he said smiling at her.

"Is it mine?" Hortense asked.

"You may wear it while you are here," said Grandfather, "and sometime it will be yours for keeps."

"And I won't be afraid of noises or anything," said Hortense.

"Not a thing can hurt you," said Grandfather. "But you must take good care not to lose it. You had better wear it under your dress, perhaps, and never take it off. Now, it is long past bedtime."

Hortense thanked her Grandfather and went into the next room to bid her Grandmother good night. Lowboy, fat and smiling, grinned at her. The cat on the hearthrug turned his head and regarded her with a long stare from his yellow eyes. Hortense felt uncomfortable but stared back, and at last the cat turned away and pretended to wash himself. Now and then he stole a glance at her out of the corner of his eye.

"He doesn't like me any more than I like him," thought Hortense as she kissed her Grandmother good night.

"Your candle is on the table in the hall, dear," said Grandmother. "Would you like Mary to put you to bed?"

But Hortense felt very brave after her exploit in the storeroom; besides which, her monkey charm gave her a sense of security. She lighted her candle and set off up the dark winding stairs all alone.

When she reached the second floor, she stopped and looked up the stairs leading to the third floor. She could see only a little way and she longed to know what it was like up there, but she felt a little timid at the thought of all those empty rooms filled with cold, silent furniture. What was it Grandfather had said? Always to face the thing one feared.

Hortense marched bravely up the stairs to the hall above. It was like that on the second floor. Hortense opened one of the many closed doors. The light from her candle fell upon chairs and dressers sheeted like ghosts, cold and silent. Hortense shut the door quickly and walked past all the others without opening them.

At the end of the hall was a door somewhat smaller than the others. It seemed mysterious, and after hesitating for a moment, Hortense turned the knob slowly.

A flight of steps rose steeply from the threshold. Hortense peered up. Above, it was faintly light These must be the attic stairs, Hortense thought, and the attic was not completely dark because the cupola lighted it faintly. When the moon was bright, it would be possible to see quite plainly. Perhaps on such a night or, better, in the daytime, Hortense would explore the attic, but she felt she had done enough for one night and closed the door gently.

As she turned to walk back down the hall, she stopped suddenly. Far away in the dark gleamed two yellow spots. Chills ran up her back, and then she told herself, "It's the cat."

Slowly she walked towards the bright spots which never moved as she neared them. Then the rays from her candle fell upon the cat crouched in the middle of the hall.

"What are you doing, spying on me like this!" said Hortense severely.

The cat said not a word. He merely stared at her with his bright yellow eyes for a moment; then he yawned, rose slowly and stretched himself, and turning, walked with dignity down the stairs. Hortense followed, but not once did the cat look back at her.

On the second floor Hortense stopped and watched the cat. When he was lost to sight in the hall below, she went to her room and carefully closed the door behind her.

She placed her candle on a stand beside the bed and proceeded to look around. The room seemed much bigger now than in the afternoon. The ceiling seemed lost in shadow far above, and the corners were all dark. There were three stiff chairs, a table, a dresser, and a highboy.

The highboy was tall and slim. The light from the candle made him seem very melancholy and sad, ridiculously so, Hortense thought.

"You are funny looking," said Hortense aloud.

The highboy, she thought, regarded her reproachfully.

"Why don't you speak?" said Hortense, "instead of looking so woebegone."

"You'll only make fun of me," said Highboy in a tearful voice.

"No, I won't," Hortense replied, "not if you'll try to look and talk a bit cheerful."

"That's easy to say," said Highboy, "but you don't have to stay in this room day and night with nobody to talk to. It gets on my nerves."

"I'll talk to you," said Hortense, "but you should cultivate a cheerful disposition. I like bright people."

"Then you'd better talk with my brother, Lowboy," said Highboy tartly. "He's always cheery. Nothing depresses me so much as people who are always cheerful. Tiresome, I say."

"You could learn much from your brother," said Hortense severely. "Why don't you go down and see him now? I'm sure it would do you good."

Highboy shivered.

"It's so cold and dark in the hall," he said. "I almost never dare go except on bright warm nights in summer. Of course I daren't go in the daytime."

"No, I suppose not," said Hortense. "However, I'll go with you, you are afraid. Grandmother has gone to bed, I think, and there will be a little fire left on the hearth."

Highboy brightened a little.

"Do you think we dare?" he said, "Suppose we should meet the cat."

"I'm not afraid of the cat," Hortense declared.

"And then there's the other one," said Highboy. "He's worse still. He's round, and bright, and hard, with sharp points all over—a terrible fellow."

"Is he the 'ha'nt,' as Aunt Esmerelda calls it?" Hortense asked.

Highboy knew nothing about that. He was only sure that the cat, Jeremiah, and his prickly companion were up to all manner of tricks and were best let alone.

Hortense, on second thought, did not wholly relish the idea of going downstairs with Highboy, but she had made the offer and so she said, "Come on, we'll go now, for I mustn't stay up too late."

Highboy stepped out of his wooden house. He looked so funny in his knee trousers and broad white collar with its big bow tie, exactly like a great overgrown boy, that Hortense laughed out loud.

"If you laugh at me, I won't go," said Highboy in a mournful voice.

"I beg your pardon," said Hortense. "It was rude of me. But you should wear long trousers you know! You are too big to wear such things as these."

"I know it," said Highboy, "but I can't change. I haven't any others. Besides, I've always worn them and I'd not feel the same in anything different. One gets awfully attached to old clothes, don't you think?"

"Boys do, I've observed," said Hortense. "Come on."

She took Highboy by the hand, and they walked cautiously down the hall. At the top of the stairs Highboy paused and leaned over the bannisters. Somebody was walking to and fro in the hall beneath with soft regular footfalls like the ticking of a clock.

"It's only Grandfather's Clock," said Highboy in a relieved whisper. "He always walks that way at night."

Highboy and Hortense descended the stairs into the hall. Grandfather's Clock was walking up and down with regular footfalls, tick-tock, tick-tock. He smiled benevolently at them as they passed but did not pause in his walk or speak to them.

"A dull life," said Highboy. "Duller than mine. You see, he has nothing to be afraid of. To be afraid of something gives you a thrill, you know. But everybody's afraid of time, and Grandfather's Clock has all the time there is."

When Hortense and Highboy entered, only the embers of the fire were left on the hearth in Grandmother's room. White Owl was wide-awake with staring eyes, but the Firedogs were evidently napping and Lowboy was sound asleep.

"Hello," said Highboy, and at once Lowboy's eyes opened wide and both the Firedogs growled.

"Come out and talk," said Highboy.

Lowboy obeyed at once. He was short and fat—not half so tall as his brother, but twice as big around—and he was dressed exactly like Highboy except that his necktie was red whereas Highboy's tie was green.

"I knew she'd bring you," said Lowboy, pointing to Hortense. "I could see she was friendly."

"She may only be a meddlesome child," said White Owl. "It never does to judge from first impressions."

"I could see that the cat didn't like her," said one of the firedogs, shaking himself and coming out upon the hearthrug, "and anybody that the cat dislikes is a friend of mine."

"Just so," said the other firedog.

They were just alike.

"I know I can never tell you apart," said Hortense. "What are your names?"

"Mine's Coal and his is Ember," said the first firedog, "and you can always tell us in this way: If you call me Ember and I don't answer, then you'll know I'm Coal. It's very easy! But if you'll look close, you'll see that my tail curls a little tighter than his, and I'm generally thought to be handsomer."

"You're not," said Ember. "Say that again and I'll fight you."

"Oh, please don't fight!" cried Hortense. "However can you chase the cat if you do?"

"That's the first sensible remark any one has made," said White Owl.

"I apologize," said Coal to Ember. "Let's not fight unless there's nothing else to do."

"Fighting is an occupation for those who don't think," said White Owl.

Lowboy nudged his brother.

"Talks just like a copy book, doesn't he?" said Lowboy.

"He has to keep up his reputation," said Highboy.

"Ssh," said White Owl, "I hear the cat."

Everybody became as still as a mouse. Coal and Ember crouched, ready to spring, and Highboy and Lowboy, rather frightened, took hold of hands and pressed against the wall. They could hear the soft pat-pat of padded feet in the hall.

Two yellow eyes shone in the doorway, and the Cat entered. He stood in the middle of the room with his tail waving to and fro and looked suspiciously from side to side.

Both Firedogs growled; the Cat spit; White Owl cried, "Who-oo-o," and flew down from his perch. In a twinkling Hortense was running down the hall, hand in hand with Highboy and Lowboy, behind Coal and Ember.

Up the stairs ran the Cat with the Firedogs after him, up the stairs to the third floor and through the door to the attic.

"I'm sure I shut that door," said Hortense. "Who could have opened it?"

She had no time to think further. Up and up she went to the attic and there stopped, panting. The Firedogs were running round and round, growling. White Owl turned his great yellow eyes in all directions.

"He isn't here," said Owl. "I can see in every corner, and he isn't here. But where could he have gone?"

Nobody had an answer to make, and every one felt that there was something mysterious in the Cat's sudden disappearance.

"I think I'd better go back," said Highboy nervously. "It's time I was asleep. Suppose we should be found way up here!"

By common consent they all moved downstairs together, going very softly. Hortense paused at Grandmother's door. She was speaking.

"I'm sure I heard something," said Grandmother.

"It was only the wind," Grandfather's voice replied.

Hortense and Highboy crept quietly to their room while the others disappeared below.

"It's good to be back safe," Highboy whispered, "but I'm so nervous I know I shan't sleep."

Hortense, however, undressed quickly and climbed into bed. Soon she was fast asleep, and the next thing she knew the sun was shining into her windows.

"It must have been a dream," said Hortense to herself, remembering all that had happened the evening before.

"Was it a dream, Highboy?" she said suddenly, looking at him.

"You may have dreamed," said Highboy irritably, "but I was so nervous I didn't sleep a wink."

Saying no more, Hortense dressed rapidly and went down to breakfast.

Chapter IV

"Highboy, and Lowboy, and Owl, and the Firedogs come out at night."

When Grandmother asked at breakfast if she had slept well, Hortense replied truthfully that she had.

"I don't know what got into Jeremiah last night," said Grandmother. "I heard something myself, and Esmerelda declares he ran about the house like one possessed. This morning we heard him in the attic."

Hortense, eating her egg and toast, thought she might tell Grandmother of last night's surprising events, but of course she wouldn't be believed. So on second thought she said nothing.

Slipping away to the kitchen when breakfast was over, she found Jeremiah begging for his breakfast and Aunt Esmerelda regarding him with hands on hips, shaking her head.

"Yo' sho' is possessed," said Aunt Esmerelda. "Such carrying on I never heard. I spec's de evil one was after yo', an' I hopes he catches yo' and takes yo' away wid him."

Jeremiah winked his yellow eyes sleepily in reply, but at the sight of Hortense he lashed his tail and turned away. Aunt Esmerelda, grumbling, gave him a saucer of milk.

"Yo' keep away from dat animal," said Aunt Esmerelda to Hortense. "No one knows de wickedness of his heart."

Hortense waited in the kitchen until Mary was free to begin her morning's task of dusting and tidying the rooms.

"May I come?" she begged.

"Sure," said Mary kindly. "I'm dusting the big parlor this morning, and there are lots of interesting things to see there."

In the big unused parlor she threw open the shutters and parted the curtains to let in the sunlight. Hortense was at once absorbed in the treasures she found. The room was filled with things which Grandfather had brought home from his travels all over the world. There were heavy, dark red tables carved with all kinds of flowers and animals, bright silk cushions, little ebony tabourets with brass trays upon them, curious vases and lacquer boxes from China and Japan. On the mantel was a beautiful tree of pink coral in a glass case, and beside it were wonderful shells and little elephants carved from ivory. On the walls were bits of embroidery framed and covered with glass, picturing bright-plumaged birds and tigers standing in snow.

Most fascinating of all were the strange weapons arrayed in a pattern upon one wall—spears, guns, bows and arrows, swords and knives, boomerangs, war clubs, bolos—weapons which Hortense had seen only in pictures in her geography and in books of travel. They all seemed dead and harmless enough now, not likely to come down from the wall and wander about the house at night. Hortense doubted whether they would even speak.

However, one was different, quite wide-awake and, Hortense could see, only waiting for a chance to leap down from the wall. It was a long knife with a green handle made from some sort of stone. Its shape was most curious, like the path of a snake in the dust. Like a snake, too, it seemed deadly, and the light that played upon its sinuous length and dripped from the point like water, glittered like the eyes of a serpent.

"What an awful knife," said Hortense.

"Those spears and knives give me the shivers," said Mary. "I've told your Grandfather I'd never touch them."

"Most of them are dead," said Hortense, "but the one with the curly blade and the green handle looks as though it could come right down at you. I'd like to have that one."

Mary jumped.

"Don't you touch it," she said severely. "You might hurt yourself dreadfully."

Hortense said no more, but resolved to ask Grandfather about the knife at the first opportunity. Sometime, when she had a chance, she would come to the parlor and talk with the knife. It must have lovely, shivery things to tell.

There was also a couch which fascinated her, a long, low couch with short curved legs and brass clawed feet. Hortense surveyed it for a long time.

"It looks like an alligator asleep," she said at last. "I wonder if it ever wakes up."

"What does?" Mary asked.

"The couch," said Hortense. "See its short curved legs, just like an alligator's? And it's long. Probably its tail is tucked away inside somewhere. Alligators have long tails, you know. I saw an alligator once that looked just like that."

"I declare," said Mary, "you are an awful child. I won't stay in this room a bit longer. I feel creepy."

She gathered up her dust cloths and broom, and Hortense went reluctantly with her.

"Do show me the attic, Mary," Hortense pleaded.

"Not to-day," said Mary firmly. "You'd be seeing things in the corners. I never saw your like!"

So for the rest of the morning, Mary dusted other rooms in which all the furniture seemed dead or asleep and, therefore, quite uninteresting.

After luncheon, however, Hortense asked Grandfather to tell her about the knife with the crinkly blade.

"That," said Grandfather, "is a Malay kris, such as the pirates in the East Indies carry. An old sea captain gave it to me. It once belonged to a Malay pirate. When he was captured, my friend secured it and gave it to me in return for a service I did for him."

"It looks as though it could tell terrible stories," said Hortense.

"No doubt it would if it could talk," said Grandfather. "It is very old and doubtless has been in a hundred fights and killed men."

"You wouldn't let me carry it?" Hortense asked.

"Gracious no," said Grandfather. "It is dangerous. What made you think of such a thing?"

What Hortense thought was that it would be a very nice and handy weapon to hunt the cat with at night, but she couldn't tell Grandfather that; so she said nothing.

"It's a nice afternoon," said Grandfather, "and little girls should be out-of-doors. Run out and see the barn and the orchard."

Hortense did as she was told, wandering about the yard, exploring the loft of the barn, and the orchard. At last she came back to the house, for this interested her more than anything else.

There were many bushes and shrubs planted close to the walls, forming fine secret corners in which to hide and look unseen upon the world without. Hortense hid a while in each of them, wishing she had some one with whom to play hide and seek.

She found one bush which was particularly inviting, for it was beside an open window of the basement. She looked in and was surprised to see that the window opened not into the basement but into a wooden box or chute that sloped steeply, and then dropped out of sight into the gloom below.

Hortense peered in as far as she could and as she did so, much to her surprise, a head appeared in the darkness where the wooden box dropped out of sight.

It was the head of a dirty little boy. As she stared at it, she recognized the little boy who had turned handsprings in the yard next door as she and Uncle Jonah had driven by yesterday.

"Hello," said Hortense.

"Hello," said the boy. "Help me out. I slipped."

He endeavored to lift himself to the chute whose edge came to his chin, but it was too slippery and he could not. Hortense stretched out her arm to help him, but the distance was too great.

"However did you get there?" Hortense asked.

"I wanted to see where it went," said the boy, "but once I got in I slipped and fell to the bottom."

"Where does it go?" Hortense asked.

"Only to the furnace," said the boy in disgust.

"Oh," said Hortense. "I thought it might go to a secret room or something."

"Can't you get a rope?" the boy asked.

Hortense considered.

"I couldn't pull you out if I did. I'll have to get Uncle Jonah."

"He'll lick me," said the boy.

"Oh, I know," said Hortense. "We'll play you're a prisoner in a dungeon, and every day I'll bring you things to eat."

But the boy didn't seem to like this idea.

"I want to get out," he said, and disappeared.

"I believe there's some sort of a door at the bottom," he said at last, reappearing, "but it opens from the other side. Couldn't you get into the cellar and open it?"

"Aunt Esmerelda might see me and ask what I was doing," she answered. "Maybe I can get by when she isn't looking. You wait."

"I'll wait all right," said the boy. "Don't you be too long. It's dark in here."

"The dark won't hurt you," said Hortense, but to this the boy only snorted by way of reply.

Hortense peeped cautiously into the kitchen. Aunt Esmerelda was seated in her chair, fast asleep.

"What luck," thought Hortense, and she tiptoed across the kitchen to the cellar door. She opened it very carefully, shut it again without noise, and crept down the stairs.

The basement was dark, but soon Hortense began to see her way and walked to the furnace. At the back of it was the wooden chute that led to the window above.

She knocked gently upon it.

"Are you in there?" she asked.

"Yes," said a muffled voice.

Hortense looked for the door of which the boy had spoken and at last found a panel which slid in grooves. She pulled at this but succeeded in raising it only a couple of inches.

"It's stuck," said Hortense.

"I can help," said the boy, slipping his fingers through the opening.

He and Hortense pulled and tugged and at last succeeded in raising the panel about a foot. They couldn't budge it an inch further.

"I guess I can squeeze through," said the boy.

Scraping sounds came from the box, and the noise of heels on the wooden sides. The boy's head appeared and then an arm. Hortense seized the arm and pulled.

At last a very dusty, grimy boy wriggled through and, rising gasping to his feet, dusted his clothes.

"What's your name?" Hortense asked.

"Andy. What's yours?"

Hortense told him. They looked at each other without further words.

"You've got to get through the kitchen without Aunt Esmerelda seeing you," said Hortense, and led the way to the cellar stairs.

"You stay here until I see if she's still asleep," Hortense said as she crept cautiously to the top.

She opened the door very gently and peered in. Aunt Esmerelda still sat in her corner, asleep. Hortense motioned to Andy, who came as quietly as he could, which wasn't very quiet for his heels clumped loudly on the stairs.

"Hush!" Hortense whispered. "Now go as fast and as quietly as you can across the kitchen. Hide behind the barn, and I'll follow you."

Andy ran across the room, but as he went out of the door he struck his toe against the sill, making a great clatter.

Aunt Esmerelda awoke with a start.

"Lan's sakes, wha's dat?" she exclaimed.

"May I have some cookies, Aunt Esmerelda?" Hortense asked.

Aunt Esmerelda's eyes were rolling.

"I 'clare I seed somefin' goin' out dat a doh. Dis yere house 'll be de def of me. Cookies? 'Cose you can have cookies, honey."

Hortense helped herself freely, remembering that Andy would want some. With these in her hands she walked through the yard and around the barn, where she found Andy.

"Cookies!" cheered Andy, and falling upon his share which Hortense gave him, he ate them one after another as fast as he could, never saying a word.

"Didn't you have any luncheon?" Hortense asked.

"Of course," said Andy, "but I squeezed so thin getting out of that box that I'm hungry again."

"I suppose," said Hortense, "that when I want a second helping of dessert and haven't room for it, all I need do is to squeeze in and out of the box and then I can start all over again."

It seemed a delightful plan.

"We might do it now and get some more cookies," said Andy, hopefully.

"Aunt Esmerelda would catch us and tell Uncle Jonah," said Hortense.

She meditated on the delightful possibilities of the box.

"We could play hide and seek, sometime when nobody's about," she said. "It's a grand place to hide."

"But we both know of it and there's nobody else to play with," said Andy.

This was very true unless Highboy and Lowboy and the Firedogs and Owl should be taken into the game. Hortense looked at Andy wondering whether to tell him of these friends of hers and of the Cat.

"If we played at night," said Hortense, "we could have lots of people. Highboy, and Lowboy, and Owl, and the Firedogs come out at night."

Andy stared at her with round eyes.

"They're the furniture, you know," said Hortense. "You can see some things are alive and waiting to come out of themselves. I'm sure Alligator Sofa and Malay Kris would play, too, if we asked them."

Andy's eyes were as big as saucers.

"Honest?" he asked doubtfully.

"They came out last night and we chased the cat, Jeremiah, into the attic where he disappeared," said Hortense. "We must find out where he went."

"Aw, you're fooling," said Andy, but he spoke weakly.

"Cross my heart 'n hope to die," said Hortense. "You come over to-night after everybody's asleep, and I'll show you."

"I suppose I could get out of my window all right," said Andy doubtfully, "but how could I get into your house?"

"By the cellar window and the wooden chute as you did to-day!" cried Hortense. "Then I'd unlock the cellar door, and you could come up."

Andy seemed not to like the prospect.

"It will be dark," he said.

"Oh, if you're afraid of the dark, of course," Hortense sniffed.

"Who said I was afraid?" challenged Andy.

"Well, come if you aren't afraid," said Hortense. "But you mustn't make any noise, of course, or they'll catch us."

Andy looked long at her and swallowed hard.

"I'll come," he said bravely.

Chapter V

"Jeremiah's disappeared again."

After dinner that night, Grandfather took Hortense on his knee and told her an exciting story, of pirates and Malay Kris.

"Is it true?" Hortense asked.

"Pretty nearly," said Grandfather. "It might be true."

"If you think things are true, then they are true, aren't they?" Hortense demanded.

"Perhaps," said Grandfather, wrinkling his forehead. "Philosophers disagree on that point. Now run off to bed."

Hortense kissed her Grandfather and Grandmother good night and went to her room.

"I hope you got a good nap to-day," she said to Highboy when she had closed the door, "because we are going to play hide and seek to-night, and Andy, who lives next door, is coming over."

"I slept all day," said Highboy, "and I'm fit as a fiddle."

"Why do you say fit as a fiddle?" asked Hortense. "Do fiddles have fits? Cats have, of course!"

"And dresses," added Highboy, "and things fit into boxes. Your grandmother says when she puts things into me, 'This will fit nicely,' so I suppose a fiddle fits or has fits the same way."

"It doesn't seem clear to me," said Hortense.

"How many things are clear?" Highboy demanded.

"Lots of things aren't," Hortense admitted. "Of course, a clear day is easy."

"And you clear the table," said Highboy.

"And clear the decks for action," said Hortense, "but that's pirates. I must ask Malay Kris about that. He's seen it happen lots of times. We'll get him to play to-night."

"Who is Malay Kris?" asked Highboy.

"He's the long, snaky knife that hangs in the parlor," said Hortense. "Then there's Alligator Sofa, too. We'll get him to play, if he'll wake up. He's so slow I suspect he'll always be It."

Highboy shivered until he creaked.

"They sound fierce and dangerous to me," he said, "worse than Coal and Ember."

"Perhaps we can set him on Jeremiah and the other one," said Hortense. "I'm longing to see the bright, round one with prickly sides. I've a guess as to who it is."

Highboy shivered again.

"Don't mention them in my hearing—please!" he begged. "You never can tell when Jeremiah is snooping about, and he's a telltale."

"Well, we needn't be afraid of Jeremiah," Hortense said. "Malay Kris will make the other one run, too, I expect."

She looked out of the window.

"There's no light on the lawn from the library," said she. "Everybody must be in bed. Let's go down."

"You hold my hand tight," said Highboy.

Hortense did so, and they stole down the stairs together.

Coal and Ember growled a bit when they entered Grandmother's room but stopped when they saw who it was.

"What do we do to-night?" Owl asked. "I feel wakeful."

"Andy's coming over," said Hortense, "and then we're going to ask Malay Kris and Alligator Sofa to play with us."

"Andy sounds like a boy," said Owl. "I hate boys. One robbed my nest of eggs once, and I swore I'd pull his hair if I ever met him again."

"That was another boy, I'm sure," Hortense replied.

"All boys are bad," Owl grumbled. "Who are Malay Kris and Alligator Sofa?"

"I'll show you," said Hortense, "but first I must let Andy in. The cellar door's sure to be locked. You all wait here until we come."

She found her way into the dark kitchen and, unlocking the door, stood at the head of the stairs. Soon she heard bumps in the wooden box.

"Is that you, Andy?" she called softly.

"Yes," said a muffled voice, and she heard him stumbling in the dark.

Andy found his way to the stairs at last and soon stood beside her. Hortense took him by the hand and led him to Grandmother's room.

"This is Andy," she said to the others.

"Let us smell him," said Coal and Ember, "so we'll know him in the dark."

They sniffed at his heels, and Owl glared fiercely at him.

"It's not the boy who robbed my nest," said Owl. "It's lucky for his hair."

"Now we'll go into the parlor for the others," said Hortense, leading the way.

It was so dark in the parlor that Hortense could see nothing; so she threw open the shutters, admitting a faint light which shone on Malay Kris and made him glitter.

"We want you to come down to play hide and seek," said Hortense.

"I'd rather have a fight," said Malay Kris. "It's a long time since I've tasted blood. Many's the man I've slithered through like a gimlet in a plank."

"These boastful talkers seldom amount to much," said Owl.

Malay Kris glared at Owl, whose fierce eyes never wavered.

"You have wings," said Malay Kris, "but anything that walks or swims is my meat. Show him to me."

"Nonsense," said Hortense sharply. "This is hide and seek and not a pirate ship."

"In that case," said Malay Kris, "I'll join you in a friendly game."

Down he leaped as agile as a cat, a trim, slim fellow with bright eyes.

"And now for Alligator," said Hortense. "He's asleep, as usual."

She shook him roughly, and Alligator spoke in a hoarse voice like a rusty saw.

"Who's tickling me?"

"His voice needs oiling," said Owl.

"A fat pig is what I need," said Alligator.

"Well we have no fat pigs," said Hortense. "We are going to play hide and seek."

"I'll play, of course," said Alligator, "but I'm slow on my feet. Now if it were a lake or river, I'd show you a thing or two."

"The point is, who is to be It? said Owl.

"Very true," said Lowboy. "He's a mind like a judge—never forgets the point."

"She's It, of course," said Malay Kris. "She thought of the game."

"Oh, very well," said Hortense.

"It would be more polite to make Andy It," said Owl. "Always be polite to ladies."

"I'll choose between Andy and me," said Hortense.

"Eeny, meeny, mona, my

Barcelona bona sky,

Care well,

Broken well,

We wo wack.

"I'm It. I'll count to a hundred, and the newel post in the hall will be goal."

There was a hurrying and scurrying while Hortense hid her face.

"Ready," Hortense called and opened her eyes. She moved cautiously in the dark hall and stumbled over something at the second step.

Slap, slap, slap, something went against the newel post.

"One, two, three for me," said a hoarse voice.

"That isn't fair. You slapped with your tail," said Hortense.

"Why isn't it fair?" said Alligator. "I wouldn't stand a chance with you running. Now go ahead and find the others while I take a nap."

"Well, there are plenty more," Hortense consoled herself. "I'll look in Grandmother's room first."

The first thing she saw was the bright eyes of Owl, who was perched on the mantel.

"I see you," said Hortense and started to run back.

But Owl flew over her head and was perched on the newel post when she arrived.

"Dear me," said Hortense, "I'll be It all the time at this rate. I wonder if Coal and Ember are in the fireplace. She looked, but they weren't there.

"I'll try the library," thought Hortense.

She hadn't more than reached the center of the room when Coal and Ember dashed past her.

"Why didn't you tell me?" said Hortense reproachfully to the bronze image of Buddha seated placidly on his pedestal. The image didn't deign to reply.

"I wish I could make him talk," said Hortense aloud.

Somebody snickered in the corner.

"Sounds like Lowboy," said Hortense.

Lowboy started to run for the door but collided with a chair.

"I've scratched myself," said Lowboy.

Hortense did not wait to console him. Instead, she ran to the newel post.

"One, two, three for Lowboy!" she called. "Lowboy's It. All-y all-y out's in free."

Malay Kris crawled out from behind the clock, and the others appeared one by one.

"Lowboy's It," said Hortense.

Lowboy shut his eyes and began to count. Hortense seized Andy by the hand and ran with him up the stairs.

"We'll hide in the attic," she whispered.

Up and up they ran, softly opened the door to the attic, and hid behind a trunk in the corner.

"They'll never find us," said Andy.

They lay quiet and heard nothing for a long time.

"Perhaps they've given up," said Andy.

"Ssh!" Hortense whispered.

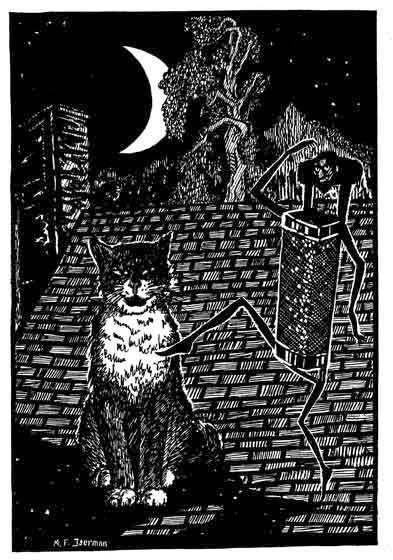

Something was running very fast up the stairs. It did not stop at the top, but raced on to the ladder which reached to the cupola above. Hortense peeped out. On the sill of the open window above stood Jeremiah with arched back and swollen tail. His yellow eyes shone like lamps.

"Of all things!" said Hortense.

Then the Cat disappeared, and they heard the soft thud of his feet alighting on the roof.

"We must see what he's up to," said Hortense.

Followed by Andy, she ran to the ladder, scrambled to the top, and peered out. The Cat was perched on top of the chimney, looking this way and that.

Hortense ducked her head in order not to be seen.

"What do you suppose he's doing there?" she asked.

"Perhaps something is after him," said Andy.

From below came a slow scratching sound. Some heavy creature with claws was coming up the attic stairs.

"Is it you, Alligator?" Hortense called.

"Where's that Cat?" said Alligator in a determined voice. "I must have him."

"He's on the roof," said Hortense, climbing down. "But what do you want him for?"

"For supper," said Alligator in his harsh voice. "He'll be furry, but eat him I will."

He started up the ladder.

"I'm old and big for such work as this," said he, "but have him I will. Push my tail a bit and give me a lift."

Hortense pushed and Andy, at the top, pulled. Out went Alligator, Hortense and Andy holding his tail while he scrambled down the roof.

Jeremiah raised his voice.

"Help! Help!" he cried as Alligator slid slowly down the roof towards him. Then, as Alligator put his forelegs against the chimney and began to lift his horrible head, Jeremiah shut his eyes and jumped.

Quick as a flash Alligator's huge jaws opened wide, and into them fell Jeremiah. Hortense could see Alligator's throat wiggle as Jeremiah went down.

Alligator crawled back slowly.

"I must seek my corner and go to sleep," said Alligator, balancing himself on the window ledge. "Hear him?"

Hortense and Andy put their ears to Alligator's back. Within they could hear Jeremiah running around and around and crying out.

"He's having a fit," said Hortense.

"A snug fit," said Alligator grimly. "He'll get used to it after a while."

Hortense and Andy were quite silent as they slowly followed Alligator down the stairs.

"It's rather horrible," Hortense whispered to Andy, "although I didn't like Jeremiah."

"I think I'll go home," said Andy.

In the hall below they found all the rest.

"Where have you been keeping yourselves?" said Owl irritably. "Ember's It, and we've waited ever so long."

"Alligator's swallowed Jeremiah," said Hortense.

"Served him right," said Owl, but Coal and Ember backed off as though fearing their turn would be next. Lowboy was sober for once.

"I want to go home," whimpered Highboy.

"Why didn't you let me run him through first?" demanded Malay Kris. "I'd have skewered him like a roast of beef."

"Too late," said Alligator, making off to the parlor.

"I suppose the party's broken up for to-night," said Owl.

All moved away by common consent. Hortense let Andy out of the back door and locked it after him. Taking Highboy, who was still shaking, by the hand, she led him up the stairs.

"That Alligator's a dreadful person," said Highboy. "I'm sure I'll not sleep at all."

Hortense, however, slept soundly and was late for breakfast. When she entered the dining room, Grandmother was saying, "Jeremiah's disappeared again. I wonder what can have got into him of late."

Mary, bringing toast, entered with a troubled face.

"Jeremiah's somewhere in the parlor, ma'm," she said. "I heard him crying under the sofa, but though I looked I couldn't see him. I called to him, but he wouldn't come. It's most surprising."

"We'll find him after breakfast," said Grandfather.

So after breakfast they all went to the parlor. Jeremiah's plaintive cries could be clearly heard. Grandfather looked under the sofa and poked around with a cane, but still no Jeremiah appeared.

"We'll have to move it out," said Grandfather. "He must be caught somewhere."

He moved the sofa out into the room and peered behind it. Jeremiah's cries came distinctly, but he was not to be seen.

"Most extraordinary," said Grandfather.

Aunt Esmerelda shook her head, as did Uncle Jonah.

"Dat cat is sho' a hoodoo," said Uncle Jonah.

"Something's moving in the sofa," said Hortense.

All looked, and sure enough there was a slight movement from within.

"But he couldn't get into the sofa!" said Grandmother.

Uncle Jonah and Fergus turned the sofa over on its back.

"There's no hole," said Grandfather, examining the sofa carefully from end to end, "but there is something moving inside!"

He opened his pocketknife and carefully slit the covering at one end. Uncle Jonah and Aunt Esmerelda retreated to the door and looked on with frightened faces.

Grandfather inserted his hand, felt around, and pulled forth Jeremiah, a very crestfallen cat.

"How did you get in there?" demanded Grandfather.

Jeremiah mewed and looked much ashamed.

"A most extraordinary thing," said Grandfather, carrying Jeremiah from the room.

Hortense followed with the others. As she went, she raised her eyes to Malay Kris, hanging in his customary place on the wall.

Malay Kris winked one bright eye at her.

Chapter VI

"I'll have the charm

That saves from harm;"

Grandmother was knitting and Hortense sat on a stool at her feet, thinking, for she wished to make a request of Grandmother and she was doubtful of Grandmother's response.

"May I ask the little boy who lives next door to come in and play?" Hortense asked suddenly.

"I didn't know you had seen him," said Grandmother.

"I've seen and talked with him," said Hortense. "His name is Andy."

"You are sure that he is a nice little boy?" Grandmother asked.

"Oh yes!" Hortense cried.

"Very well, then," said Grandmother. "You may ask him to come after luncheon."

Hortense did so. After luncheon she and Andy climbed to the attic, which Hortense wished to see in the daytime, for at night she had learned very little about it.

It was a great square attic with a roof that sloped gradually to the floor from the cupola, which was like the lamp high above in a lighthouse. Like all proper attics it held old trunks, furniture, and all kinds of things. In the drawers of the bureaus and wardrobes were old suits and dresses, and in the trunks, other dresses and suits and old hangings. Andy and Hortense took them out and dressed in them—and played they were a lord and a lady, and pirates, and Indians. Then they sat down to eat the four apples which Hortense had thoughtfully brought with her.

"Where do you suppose the Cat hid the night I followed him and he disappeared?" Hortense asked.

"There are lots of corners to hide in," said Andy, but Hortense was sure that the Cat had some particular place; so Andy and she crawled all around the attic under the eaves, looking behind every trunk and into every corner. Yet they could find no place that seemed especially secret.

"There's no secret corner," said Andy, sitting down beside the big chimney and leaning his back against it.

But as he spoke he suddenly began to disappear through the floor and only by catching the edge of it did he save himself. He and Hortense were too surprised to speak for a moment. Then they knelt on the edge of the opening and peered down.

"It's a trapdoor," said Andy. "We must find out where it goes."

He pushed the door to one side and revealed a little staircase.

"Are you afraid to go down?" Andy asked.

"Of course not," said Hortense. "You go first."

Andy led the way and Hortense followed. A few steps brought them to a small room. It was dark, but the light from the trapdoor enabled them to see a little after a while. There was nothing in the room but a large chest.

"Shall we open it?" Andy asked.

"Of course," said Hortense.

By pulling and tugging they succeeded at last in lifting the lid.

"It's empty," said Andy much disappointed. "I hoped it might be full of gold and jewels."

Hortense had a sudden thought.

"This is where Jeremiah went the time we couldn't find him."

Andy was unconvinced.

"A cat couldn't open a trapdoor," he said.

"Maybe Jeremiah could. He's no ordinary cat. Besides there's another one."

"Another cat?" Andy demanded.

"No. Somebody else we haven't seen, but I can guess who it is."

"Who is it?"

"I won't tell yet—not until I'm sure. But we'll see him. Maybe we'll surprise him and Jeremiah here some night and take them captive."

"Hello," said Andy as he put his foot on the stairs. "What's this?"

Beside the chimney was a black hole and fastened to the chimney was an iron bar like the rung of a ladder. Andy peered down.

"There's another rung," he said. "I wonder where this ladder goes?"

"We'll have to find out," said Hortense. "Dear me, this is a most mysterious house."

Andy put one foot on the ladder and began to descend. Soon his head disappeared from sight.

"It goes down and down, probably to the basement," he called. "Come on."

Hortense obeyed, and down and down they went. It was very dark, but now and then a little chink beside the chimney let in a ray of light.

"Maybe it goes to the middle of the earth," said Andy from below. "No, here's the bottom at last."

Soon Hortense stood behind him. Gradually, as their eyes became accustomed to the dark, they could see a little.

"Here's the way," said Andy at last.

"But here's another passage," said Hortense.

"We'll try mine first," said Andy.

They had walked only a few steps when they came to a wooden panel.

"It's like the one that I crawled through the other day," said Andy. "Help me to move it."

It moved slowly, but finally they raised it until they could crawl through.

"I believe this is the chute I came down when you found me," said Andy.

He stood up.

"There's the basement window," he said, "and here's the little door I crawled through. Now we can get out."

"We must see where the other way goes first," Hortense reminded him.

"I'd forgotten," said Andy.

Back they went to the foot of the ladder and then down the other way which grew smaller and smaller and suddenly stopped.

"Let's go back, there's nothing here," said Hortense.

Andy stood still, absorbed in thought.

"It can't end in nothing," said he. "Who would dig a tunnel to nowhere?"

He felt the end of the passage with his hands.

"It's wood," he announced. "It must be a door. Yes, here's a little latch."

He opened the little door and, lying on his stomach, looked down the tunnel beyond. It was neatly fashioned and quite light but curved away in the distance so that the end was not visible—only a shining bit of the wall.

Hortense spoke the thought of both.

"If we were only small enough to go down it and see where it leads," said she.

But alas, it was far too small for that.

"Probably Jeremiah goes through it," said Hortense. "Where do you suppose it goes?"

"Perhaps to the middle of the earth, or to a cave filled with diamonds and gold," said Andy.

"Or maybe to the home of the fairies."

"Well, we can't know, so there's no use thinking of it."

"Still, if we watched it sometimes, we might see who goes down it," Hortense suggested hopefully, "and if it were a fairy, we might talk with him."

"We might do that," Andy agreed.

"But probably they'd know we were watching and keep hid."

They returned the way they had come, crawled through the wooden box. Into the basement, and went to the head of the cellar stairs.

"I'll see if Aunt Esmerelda is asleep," said Hortense. "If she is, we'll tiptoe across the kitchen, get some cookies, and eat them in the barn."